Nontombi Naomi Tutu. Photo: All Saints Church, Beverly Hills

The Rev. Nontombi Naomi Tutu is very much her father’s daughter, yet from an early age was determined to chart her own course.

The third child of 1984 Nobel Peace Prize winner Archbishop Desmond and Nomalizo Leah Tutu, she bears a striking resemblance to her father but has emerged from his shadow as an activist, advocate and priest in her own right.

“What is funny is, that having my dad as my dad and looking so much like him, I was clear from very early in my life that I was never going to be a priest,” Tutu told The Episcopal News during a recent virtual interview. Engaging and joyful, she pauses, laughing: “I didn’t care if there was no other job available.

“Even when I first felt a call to ministry, at about 24, I pushed it away and ignored it and fought it and I did that for the next 25, almost 30 years.”

Ordained in 2017 in the Episcopal Diocese of Tennessee, Tutu joined the staff of All Saints Church in Beverly Hills in September 2020 as associate rector for pastoral care. Her reflections about growing up in apartheid South Africa, carving her own niche, and racial reckoning in the United States form the inaugural interview for an ongoing Episcopal News “Voices of Justice” series about Episcopalians seeking “the dignity of every human being” within the Diocese of Los Angeles.

A video interview with Tutu is here.

How do you remember apartheid? Were you aware of your father’s fame?

At 6, Tutu was sent to boarding school in Swaziland, where she spent three months at a time. She recalled the two-day family trips to drop her off and pick her up being planned around which gas stations and restaurants served Black people.

“Most of the shops on that journey would only serve Black people from a window,” she recalled. “And very often, they gave Black people stale bread, milk going off. So our whole experience was based on the fact that in our own country we were not seen as full human beings and full citizens.”

Although her father was an activist priest in South Africa, he was “just my dad,” and relatively unknown in the U.S. when she arrived at 18 to attend Berea College in Berea, Kentucky. There she earned a bachelor’s degree in economics and French.

Much later, while in divinity school, she began the discernment process. Still squeamish about it, she recalled laughingly: “My very first meeting with the parish discernment committee … with the Commission on Ministry … I said, I’m ready to hear it’s actually no, it’s not what I’m called to do.”

Given the current racial reckoning happening in the U.S., what can we learn from the TRC—South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission?

The TRC was intended as a compromise, to balance the outcry for justice for torture and murder under apartheid, and those “in the white community who were saying ‘let bygones be bygones, this is a new South Africa. Let’s wipe the slate clean,’” Tutu said.

The commission offered an opportunity for both victims and perpetrators to tell their truth and, in that sense, “gave the nation a common history,” she said. “It took away people’s ability to say, ‘I didn’t know’ or ‘that’s not my story.’ It said if you are willing at this point to celebrate how far we have come, you can’t do that celebration unless and until you acknowledge and accept why did we need to come that far, to acknowledge what happened in our country, the level of atrocities, the number of people killed, the number of families who don’t know even to this day what happened to their loved ones.”

According to the Human Rights Commission, about 21,000 people died in South Africa during apartheid – of whom 14,000 died during the six-year transition process from 1990 to 1994.

“A huge part of any healing is an acknowledgement of the history, acknowledgment of the story, but the whole story,” Tutu said. “That was a major achievement and I say that particularly living in the U.S. and hearing people try and choose which part of their history they’re willing to claim.”

Yet “there is still very much an apartheid economy” in South Africa, she said. “Most economic power continues to reside in the hands of white men. The vast majority of Black South Africans have not seen economic benefit. So, we haven’t healed. We cannot have healed without some remedying, some recompense, some reparation.”

Her experiences in the U.S., have been “like another South Africa, basically,” Tutu said. A single mother of three, she raised her children in Tennessee and recalled feeling her son was targeted by an educational system that labeled him “a problem.”

After Tutu’s repeated visits to the school to advocate for him, the situation changed. But, she said, “if I did not work in a job that allowed me to say ‘hey, I’m going to be late because I have to go back to my son’s school for the 15th time,’ what would have been his experience?”

And despite the racial reckoning happening in the U.S., Tutu doubts “there’s going to be a national move toward the kind of acknowledgement and healing the TRC offered us in South Africa. I don’t think there’s the political will in either party for that to happen.”

Such activism needs to come from churches and universities, “doing that for their community,” she said. “It’s going to have to come from the grassroots. It’s going to have to come from us. This is part of the role of the church. This is the place the church can play a really important role.”

How do you view your current ministry?

Imprinted upon her ministry is her memory “that in order to be baptized as an African child I needed to have a Western name,” she said. “My Christian name could not be Nontombi, the Xhosa name that my family gave me.”

Also, “the church I belonged to, the church that my father was a priest in, paid Black and white priests differently … and never sent Black priests to be rectors of white parishes. So, part of my call is to call the church to account, to call the church to live fully into the gospel that we claim is ours. A gospel that comes out of an experience of oppressed people, a gospel that says each of us is made in God’s image.”

Tutu said a focus on racial justice, economic justice, and paying attention to who is at the table and who isn’t, is central to whatever ministry she engages.

“This is who I am called to be,” she said. “It is who the church is called to be, and the church has ignored that call probably since Constantine. Once we became the church of the empire, we forgot that we were a church founded by a group of people on the margins, a group of brown people who were living in an occupied country, bearing the brunt of empire.”

It’s been a heartbreaking year, with the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and other unarmed African Americans. Can you comment about these events?

“Any parent of a Black child knows the agony of watching your child leave the house and wondering whether they’re going to come back alive. Not because your child is evil or a criminal or anything like that, but just the fact that your child walks this country in a black skin,” she said.

After the Feb. 23, 2020 killing of Ahmaud Arbery while he was jogging in rural Georgia, she challenged the North Carolina church she was serving: “How does white America ignore the level of trauma that is just about parenting as a Black person?

“How is that even something this country will not take in as a traumatizing lived experience of Black people?”

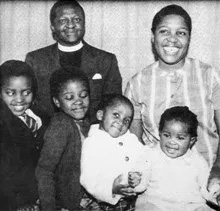

Desmond and Leah Tutu pose with their children, Trevor Thamsanqa, Theresa Thandeka, Naomi Nontombi and Mpho Andrea, circa 1965.

Where do you find hope?

Her maternal grandmother taught her about hope, Tutu said. “When I was 32 and voted for the first time in my life, my grandmother was 90. She told me on that day, that the election was called for President Mandela, … ‘I believed that this day would come in your lifetime, that the struggle we were going through was about liberating our grandchildren. It is just amazing that I’ve lived to see it myself.’”

“She voted for the first, and last time. She died three years later.” Her grandmother’s struggle, and the struggle of generations for freedom, gives her hope, Tutu said. “Whatever I am doing right now I will probably die still being terrified when I see my son’s name coming up on my cell phone but maybe he and his spouse will not have that terror for their children.”

Also, the knowledge that “I come from a lineage of people who have endured the most awful atrocities around the world and yet have continued to stand and to believe in the struggle for justice and have refused to give up their humanity in the face of dehumanization — that is a foundation of hope for me.”

And there is hope, says Tutu, in recognizing, that “I am created in God’s image.

“The hope that comes from that is that one day we will come to a point where we will recognize when God was making us in God’s own image, that meant brown, white, male, female, all of us are God. God’s image.”

She laughs again, recalling memories of childhood arguments with siblings: “My father would say to us, do you know when you are looking at your sibling you are looking at the image of God? Instead of cussing them out, you should be genuflecting.

“And we were like, yeah, right, fine. She’s still an idiot. But that idea has lived on in me even when I struggle with it. My hope is that if we live this faith, there will be a point where we cannot recognize God’s image in ourselves without recognizing God’s image in others.”