Dennis Gibbs and Greta Ronningen of Prism and the Community of Divine Love are pictured during a 2019 meeting with Bishop John Harvey Taylor. Photo: John Taylor

For the Rev. Dennis Gibbs and the Rev. Greta Ronningen, co-directors of Prism, the diocesan restorative justice ministry, serving “our friends inside” the jails of Los Angeles County and some other California prisons has taken on both a clarity and a sense of urgency during the pandemic.

“I want to encourage everyone to remember those that are sitting somewhere tonight in an 8 x10 cell with dirty water and no way to contact their families,” Gibbs said. “Try not to forget our friends, that’s what I want to say.”

For Gibbs, a deacon who founded the ministry 16 years ago, such remembering can be as simple as praying for the incarcerated during weekly worship, especially given some reports that as many as 80% of Los Angeles County jail inmates have tested positive for coronavirus.

Chaplain access to inmates — previously limited at best — has ceased altogether during the pandemic. And positive support systems, such as 12-step programs, have also been halted, at least temporarily.

“Where are the inmates” among published lists of those slated to receive vaccinations, Gibbs wondered aloud at a recent Zoom organizing meeting of prison ministry counterparts from across The Episcopal Church. “They (the inmates) are among the most vulnerable in our society, just as vulnerable as those in nursing homes and other closed environments.”

Members of the “embryonic” Episcopal Prison Ministry Community network, from West Oregon to western North Carolina, from Arizona to Florida, have been meeting online.

Concern for the 17,000 men and women in the L.A. County jail system and thousands of other inmates across the state and the nation helped inspire Ronnigen’s and Gibbs’ desire to create the network.

For the Rev. Kim Crecca, who facilitates prison ministries in the Diocese of Arizona, “There is a power that comes with this national effort, especially when we coordinate our efforts … and get focused on legislative actions within states. It helps everyone. The network can be a very powerful presence for us in making reforms nationally and statewide.”

Ronnigen said the network aims to share resources, best practices and to create opportunities for learning, mutual support and advocacy.

“We realize that a lot of really great work is being done across The Episcopal Church, and that we’re not talking to one another,” she said. “That sparked our desire to find a way to reach out and try to make connections. There’s a lot of innovative church going on inside prisons, besides just chaplaincy.”

Along with the spike in COVID cases, she and Gibbs have witnessed an intense need for connection, including a near quadrupling of inmate participation in a companion program with the Community of Divine Love. The monastery is an Episcopal religious community in San Gabriel they founded in the tradition of St. Benedict, with a special focus on prison ministry.

“Divine companions” who develop a three-fold rule of life comprising stability, obedience, conversion and a commitment to nonviolence, represent, “the fastest growing component of our monastic community,” Gibbs said. “We now have about 11 divine companions. Six months ago, we had three.”

While waiting to resume their prison visit ministries, Ronnigen and Gibbs also write daily to inmates and have developed a monthly newsletter with featured inmate reflections.

“They get the excitement of something they wrote being published,” Ronnigen said. “We have people writing from the facilities about their life in recovery.”

One such is Rose B., who shared in the January 2021 newsletter about a past scarred by violence and abuse:

It was my own mother who decided to beat on me. Growing up, it was hard to just look at her and remember to breathe … I hate looking in the mirror, because nothing seems like it’s getting any clearer. It hurts me more than all the tears I didn’t get to cry. But let me stop dwelling. Let me not pry. Let’s talk about this past I’ve held in all this time. Because I am a survivor.

Sam Pillsbury, deacon, serves as a chaplain in the Twin Towers prison when not barred by pandemic restrictions.

The Rev. Sam Pillsbury, a former crime reporter, former federal prosecutor and Loyola Marymount University law school professor, now a deacon of the Diocese of Los Angeles, said he hopes the network can help facilitate access to inmates.

“Information can be very difficult to get and it will be helpful to hear how different facilities work, what they allow and don’t allow,” said Pillsbury who serves most in the Twin Towers.

“In jail ministry, you are seeing new people all the time. People move in and out. Over time, working with the administration is one of the hardest things. There are some people you make connections with, but in general you’re doing quite different work than they are, and there are lots and lots of restrictions. Having a good working relationship, that’s hard over time.”

Church of Our Saviour parishioner Sharon Matsuhige Crandall has volunteered for the last eight years, mostly at the Men’s Central Jail in Los Angeles, where the conditions are horrendous and getting access to inmates can be challenging.

“It is really difficult getting in to see people,” Crandall told The Episcopal News recently. “I would drive down to the jail and park, get through security and go to do a class or a church service or meet with someone one-on-one and they’d say, ‘Sorry we’re too busy today.’ That takes its toll week after week, when you’re giving your time and then you’re just turned away.”

She and Pillsbury both say the new network can assist with providing grace-filled resources, and advocate against unsafe prison conditions, systemic racism and mass incarceration.

The Men’s Central Jail, “is dark and dim and dangerous and unsanitary and it just needs to go,” Pillsbury said. The jail, built in 1963 and expanded during the 1970s, is slated for replacement by 2028. It houses about 4,000 men in cramped cells, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“A lot of the cells don’t have proper lighting,” added Crandall. “It floods often. The men will show me, they have sores on their feet that get infected from the flooding and the sewage.”

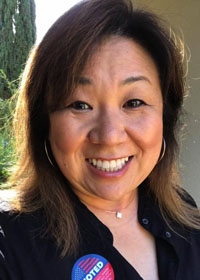

Lay chaplain Sharon Matsuhige Crandall volunteered at Men’s Central Jail in Los Angeles for about eight years before the pandemic.

The network also could share resources for inmates “more representative of what The Episcopal Church stands for within jail and prison walls,” she said. “We’re there to support them on their spiritual journey, wherever that is, not to necessarily evangelize and proselytize.”

Currently, “most of the jail resources that are available, I won’t even hand out,” Crandall said. “I find the theology is outdated and not very relevant to young people today. It’s also very exclusive and kind of damning in many regards.”

Hopefully, the network will also provide mutual support “among those who understand your experiences, without you having to explain it,” she said.

“Chaplaincy in general is lonely and isolating,” said Pillsbury, who serves among inmates with serious mental health diagnoses. “It goes along well for a while and then you have a couple of experiences that are difficult, and you need others to say, ‘yeah, I went through that, too, and it’ll pass.’ It is really helpful, in the long run, to hear challenges others are facing and how they’re dealing with them.”

Crandall is also hopeful the network collectively will tackle the systemic challenges of mass incarceration because “at the heart of it, we know this is racism. It’s the extreme imbalance of socioeconomic and racial boundaries and it’s so important that the church as a whole be aware and make it an important issue. This is the heart of it all.”

Pillsbury agreed: “There is strength in knowing we don’t have to reinvent everything, strength in knowing what others are doing. This is not what most people think of as what The Episcopal Church is doing but it is what we are doing. This is the new Episcopal Church.”

More information about Prism is here. The ministry also maintains a Facebook page here.