The annual celebration of Absalom Jones, first black man to be ordained a priest in The Episcopal Church, was held Feb. 26 at Church of the Holy Faith, Inglewood. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Absalom Jones, first Black man to be ordained a priest in The Episcopal Church in the United States.

[The Episcopal News] The Rev. Margaret McCauley invited worshippers at the Feb. 26 annual diocesan Absalom Jones celebration to join the H. Belfield Hannibal chapter of the Union of Black Episcopalians, the NAACP, the Urban League, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and Black Lives Matter, because “we’ve got work to do.”

McCauley, deacon at St. John’s Cathedral, Los Angeles, and guest preacher for the joyous service at Holy Faith Church in Inglewood, compared Jones’ refusal to move to the balcony of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in 1786 to today’s Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

“When he was confronted with ethnic hatred in St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, he and Richard Allen led the Black people out of the church. This is an early example of Black Lives Matter,” McCauley said. Jones, a popular preacher, had increased the membership of the church ten-fold, which frightened the white congregation, who insisted Jones and other Black members sit in a balcony.

When Jones refused, he and Allen were removed from the church. Allen started the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Jones founded the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia and became the first person of African descent to be ordained a priest in The Episcopal Church.

Guy Leemhuis pours out a libation of water to “bring the ancestors into the room” at the Feb. 26 Absalom Jones service. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Episcopalians from across the diocese filled Holy Faith for the annual observance, which included the pouring out of water as a libation to “bring the ancestors into the room,” according to the Rev. Guy Leemhuis of St. Luke’s of the Mountains, La Crescenta.

He called upon such historic names as Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Thurgood Marshall, James Baldwin, Nikki Giovanni and Hank Aaron, “thinkers and seekers who led us along and broke color barriers.”

Other names included those deprived of justice. Like “Emmett Till … Trayvon Martin … they did not get justice. We call them into the world as they beckon us to continue the struggle for justice. We call all of those people on whose shoulders we stand, who said, no, we will not go back into the wilderness. We will follow the light of Christ that will reconcile us to our neighbors, and we will be together in the great getting up in the morning.”

Deacon Margaret McCauley calls the congregation to get involved in racial justice work during her sermon at the Absalom Jones celebration. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

The service, which also featured lively music and singing, handclapping, dancing, and celebration, followed by a soul food dinner in the church hall, was organized by the diocesan Program Group on Black Ministries and the H. Belfield Hannibal UBE chapter.

Bishop John Harvey Taylor recalled that, while Feb. 13 is Jones’ feast day in the church calendar of saints, “I am not sure that this great freedom fighter, prophet and preacher wouldn’t haven’t preferred New Year’s Day,” as a celebration.

Taylor said Jones reserved Jan. 1 every year “for a stem-winding sermon,” focused on a little-remembered clause in the U.S. Constitution (Section I, Article 9) “that prohibited Congress from outlawing the slave trade before Jan. 1, 1808.

“It was a shameless compromise with the slave powers themselves, which made it impossible for the United States to eradicate the sin of trafficking in human beings, even if it wanted to, for 20 years after the Constitution was adopted,” Taylor said. In 1807, then-President Thomas Jefferson signed a statue outlawing the slave trade, “written to take effect the second the 20-year moratorium expired … although most of those already kidnapped from their homes and enslaved would have to wait until the Civil War to receive their freedom,” Taylor said.

Celebrant Joseph Oloimooja, Bishop John Harvey Taylor and preacher Margaret McCauley clap and sing along to a gospel hymn at the Absalom Jones celebration. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

On Jan. 1, 1808 at St. Thomas’, the church he founded on July 17, 1794, Jones preached his legendary thanksgiving sermon, which Taylor quoted: “Let the first of January, the day of the abolition of the slave trade in our country, be set apart in every year, as a day of public thanksgiving for that mercy, that the history of the suffering of our brethren and of their deliverance descend by this means to our children to the remotest generation. And, when they shall ask in time to come, saying what mean the lessons, the songs, the prayers, and the praises in the worship of this day? Let us answer them by saying the Lord on the day of which this is the anniversary abolished the trade which dragged your fathers from their native country and sold them as bondmen in the United States of America.”

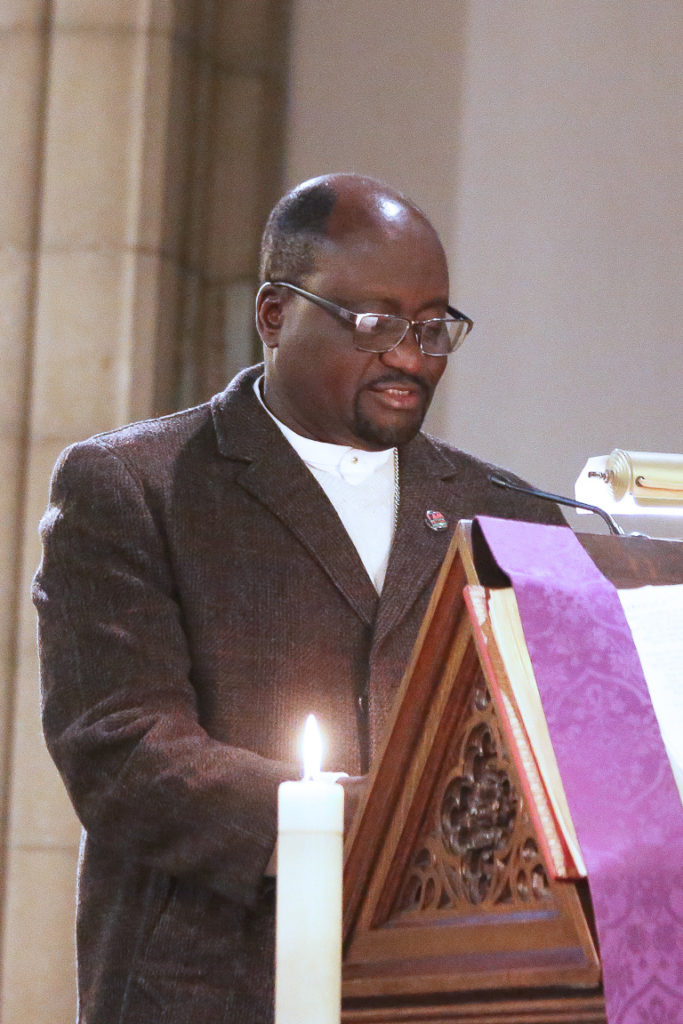

George Okusi, rector of St. John’s Church, Costa Mesa, reads a litany of prayers. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Jones: led by the Spirit

Although Jones was born into slavery in Delaware in 1746, the movement of the Spirit enabled his lifelong commitment to advocacy and service, McCauley said.

When Jones he was 16, his mother and siblings were sold. “His owner brought him to Philadelphia, where he served as a clerk and a handyman in a retail store. He was able to work for himself in the evenings and, miracle of miracles, he got to keep his earnings,” McCauley said. “He briefly attended a school run by Quakers and learned mathematics. In 1770, he married Mary Thomas and purchased her freedom, and it was not until 1784 that he became free himself through manumission.”

“We talk about every woman’s dream come true,” McCauley said. “He purchased freedom for his wife. He wasn’t free. And he set her free.” Jones also owned several properties by the time he was able to purchase his own freedom, in 1784. He was ordained a deacon in 1795, and a priest ten years later. “What a day that must have been. What a celebration,” McCauley said.

Jones died Feb. 13, 1818, at his home in Philadelphia, the day he is commemorated in the church calendar. “His ashes are enshrined in the altar of the Absalom Jones chapel at the African Episcopal Church in St. Thomas in Philadelphia, and a memorial stained-glass window commemorates his life, and his work,” McCauley said.

Jones’ life and witness are emblematic of today’s BLM, she added: “This multiethnic, multiracial group of young people … are really refusing to believe that anybody’s life is without value.”

Canon Suzanne Edwards-Acton, co-chair of the Program Group on Black Ministries, welcomes the congregation to the Absalom Jones service. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Although February has been designated as Black History Month in the United States, “we are not Black only during February,” McCauley said. “The celebration of our history may have passed, but who we are has not. The good news is that Black people get to publicly celebrate our contributions to the development of humankind.

“The bad news is, we are reminded that we are not truly free. Can you believe I am hated because of the color of my skin and there is no closet in which I can hide.”

Racism breeds fear, she said. “This is not what our God tells us. Racism includes … acceptance of negative stereotypes and discrimination and, in some cases, these define us. So, why should so why should we – Black, White, Asian, gay or lesbian – why should we accept this treatment? Like it’s our lot in life? It is not what our God has decreed.”

Three great moments in life include: “the Jesse Jackson moment when we try to keep hope alive,” she said. “There’s the Jiminy Cricket moment when we’re having high hopes. And there’s the Martin Luther King, when we are free at last. So remember … God loves us and commands us to love one another.

“It is not difficult for us to love one another,” she added. “We are all exhausted sometimes, by the struggle of just existing, so on behalf of all the Black people in the world, we welcome the love that Jesus Christ commands us to share one with another.”

Leemhuis also announced a weekly Evensong series of “Lament, Hope and Call to Action for Black Lives,” to be held at 7 p.m. on Wednesdays during Lent at the historically Black churches in the Los Angeles area, beginning March 8 at St. Barnabas’ Church in Pasadena. Other services will follow: on March 15, at Christ the Good Shepherd Church, Los Angeles; March 22, at the Church of the Advent, Los Angeles; and March 29, at St. Timothy’s Church, Compton. The diocesan community is invited to attend.

Attendees at the Absalom Jones service join in singing. Photo: Janet Kawamoto