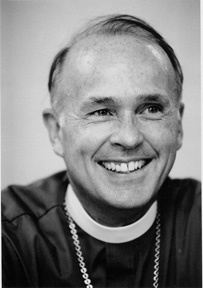

Bishop Frederick H. Borsch

Editor’s Note: The Rt. Rev. Frederick H. Borsch, fifth bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles, was among community and organizational leaders who served as witnesses testifying to the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department, known as the Christopher Commission and so named for its chair, Warren Christopher, who went on to become U.S. Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton. Following is the text of Bishop Borsch’s testimony to the commission, which L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley appointed after the beating of Rodney King by L.A.P.D. officers on March 3, 1991.

We have a long distance to go to reach any ideal state of community in Southern California, but in our churches and in many other places there are daily examples of people of different cultures and group sharing with and supporting one another.

In a number of ways the policemen and policewomen of Los Angeles are supportive and protective of this diversity and interaction. We can take pride in these numerous examples of support and cooperation among peoples in this diverse and complex region. The Christopher Commission has been created to help us find ways to restore that pride that has been harmed, for the pride itself can be both a resource and a guide to us in strengthening harmony, democracy, and community in our city.

We all need to recognize, however, that the harm that has been done is severe, and that the source of the harm is a sickness that runs deep in our police department, in our society, and in the human heart. That sickness has a number of symptoms – among them insecurity and anger. At a deeper level, fear is both a symptom and a cause – making people afraid of what is different, afraid of each other. Out of the wisdom of our tradition we would understand the root cause to be sin – the desire to put self or one’s family or group so at the center of concern that there is no real love and therefore no real understanding of others and no strong care for the larger community.

There is a question in our Christian baptismal covenant which calls upon us to respect the dignity of every human being. I do not believe the police officers involved in the now notorious action would have done what they did to Mr. King if they had had some similar thought in their heads and hearts that fateful night.

After the beating of Mr. King, I heard a number of stories from members of our churches. One that has particularly stuck in my mind was told by a distinguished lay official in our diocese – a black man who has lived in Los Angeles for a number of years. He told me of the times that he had been stopped for no apparent reason, ordered out of his car, spread-eagled and insulted. He told me it was hard to relate such stories because he found such instances so humiliating.

This is a well-dressed, well-educated man driving a nice automobile. One shudders when one thinks of the times and ways similar things have happened to other people because of their skin color or ethnic group.

Not only in Los Angeles but in many parts of our country, the major task of police is too often seen as protecting the well-to-do and those who are relatively well off from those who have less or little. I think this attitude is pervasive and affects every aspect of police work from recruitment and training to organization and strategy. In subtle if not open ways it is an assumption encouraged by elected and non-elected officials. Because people of color are a disproportionate number of the less well-off in our society, the assumption fosters and reinforces prejudicial racial attitudes and actions.

I would argue that we must work hard to alter that assumption or all else we accomplish will end up only treating symptoms. In a true democracy all people should be entitled to equal police support and protection no matter what their economic circumstances. Indeed, there are obvious good reasons for holding that most police work should be dedicated to the support and protection of those in society who are more victimized and less able to protect themselves.

To be truly effective, the change in this ordering of priorities must come from courageous elected officials and from the people themselves. To begin with, however, it must be written into the training and police of all police and receive especially effective expression from those who lead the department.

The power of police to protect the community is more effective the less violence is used. Every time violence is used, the effectiveness of the badge and the uniform is lessened because a stable and just order cannot, in the long run, be enforced by violence. This understanding does not mean that force can never be used, but it runs directly counter to the belief that the use of violence strengthens the authority and power of police by creating fear of them.

I believe the City of Los Angeles needs to have a genuinely independent Police Commission, chosen by elected officials, but then protected from any interference. This commission, using investigators other than the police themselves, needs to have the means to investigate all serious allegations against police behavior.

The alternative to this fully independent commission is that the elected officials themselves would become directly responsible for the conduct of the police. This solution has some merit, but elected officials should not attempt to have it both ways, holding a body other than themselves responsible while claiming authority over that body.

I also hope for three other changes in the local police department:

- More women police – I would say many more women police. I believe women police are and can be trained to be more likely to look for ways rather than force and violence to resolve difficult situations.

- More police representing different racial and ethnic groups.

- More police out of cars, visible and known in the daily life of our communities.

What I am sure many of us look and hope for is a police department that can become more fully supportive of a multi-ethnic society and take pride in the strengths this brings to our region.