Attorney and justice equit

Attorney and justice equit y advocate Bryan Stevenson didn’t wait for the government to create museums and monuments detailing the sins of slavery and its aftermath. He did it himself and made them look governmental. The Legacy Sites he and his colleagues at the Equal Justice Initiative established in Montgomery, Alabama include The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and Freedom Monument Sculpture Park.

y advocate Bryan Stevenson didn’t wait for the government to create museums and monuments detailing the sins of slavery and its aftermath. He did it himself and made them look governmental. The Legacy Sites he and his colleagues at the Equal Justice Initiative established in Montgomery, Alabama include The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and Freedom Monument Sculpture Park.

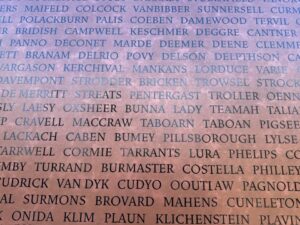

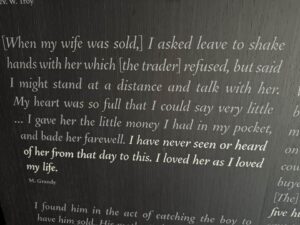

The casual visitor would not notice that they were not federal installations. Like our most stunning public monuments, they grasp eternity’s hand. The sculpture park, along the Alabama River, a notorious passage for human trafficking (giving us the expression “sold down the river,” which we should excuse from polite conversation), centers a 43-foot-tall, 155-foot-long monument bearing all 122,000 surnames imposed on enslaved people and their descendants as of the 1870 census. Enslaved people could expect to be sold up to six times and were almost always separated from parents, spouses, and children. Families’ last moments together were sometimes called “the weeping time.”

The casual visitor would not notice that they were not federal installations. Like our most stunning public monuments, they grasp eternity’s hand. The sculpture park, along the Alabama River, a notorious passage for human trafficking (giving us the expression “sold down the river,” which we should excuse from polite conversation), centers a 43-foot-tall, 155-foot-long monument bearing all 122,000 surnames imposed on enslaved people and their descendants as of the 1870 census. Enslaved people could expect to be sold up to six times and were almost always separated from parents, spouses, and children. Families’ last moments together were sometimes called “the weeping time.”

Once freed, many spent the rest of their lives trying unsuccessfully to track down their loved ones. Records were sketchy. Successive owner–abusers would often assigned people a new name. Today, thanks to EJI, you can search the surnames digitally. One of my best friends when I was growing up in Detroit was from a big family called Sewell. I learned that, in 1870, about 750 formerly enslaved people named Sewell lived in the U.S., some, probably, my friend Don’s forebears.

Once freed, many spent the rest of their lives trying unsuccessfully to track down their loved ones. Records were sketchy. Successive owner–abusers would often assigned people a new name. Today, thanks to EJI, you can search the surnames digitally. One of my best friends when I was growing up in Detroit was from a big family called Sewell. I learned that, in 1870, about 750 formerly enslaved people named Sewell lived in the U.S., some, probably, my friend Don’s forebears.

Stevenson and EJI expressed the structure’s heft and permanence by calling it the National Monument To Freedom. They didn’t ask the nation’s permission, just history’s — and just in time. Trump, our self-appointed national curator, thinks we’ve agonized enough about slavery. Last March, he fired off an executive order attacking Washington, D.C.’s National Museum of African American History and Culture for accentuating what he referred to as the negative. Its respected executive director stepped down at about the same time.

Stevenson and EJI expressed the structure’s heft and permanence by calling it the National Monument To Freedom. They didn’t ask the nation’s permission, just history’s — and just in time. Trump, our self-appointed national curator, thinks we’ve agonized enough about slavery. Last March, he fired off an executive order attacking Washington, D.C.’s National Museum of African American History and Culture for accentuating what he referred to as the negative. Its respected executive director stepped down at about the same time.

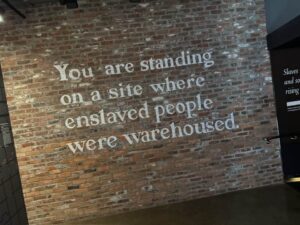

For now, the Smithsonian website reveals no evidence of additional interference by Trump, at least at the NMAAHC. But one thing’s for sure. His executive orders have no bearing on the content of the Legacy Sites. Washington would like to whitewash the story of slavery, but not Alabama. Those of us attending a National Association of Episcopal Schools conference on equity and justice visited the sites on Wednesday. It was my second visit to the Legacy Museum. The spine of its story connects slavery with Jim Crow with 21st century mass incarceration. The exhibits show how the false narrative of racial hierarchy, used to justify the unjustifiable, remains alive in the disproportionate rates of the imprisonment of people of color.

For now, the Smithsonian website reveals no evidence of additional interference by Trump, at least at the NMAAHC. But one thing’s for sure. His executive orders have no bearing on the content of the Legacy Sites. Washington would like to whitewash the story of slavery, but not Alabama. Those of us attending a National Association of Episcopal Schools conference on equity and justice visited the sites on Wednesday. It was my second visit to the Legacy Museum. The spine of its story connects slavery with Jim Crow with 21st century mass incarceration. The exhibits show how the false narrative of racial hierarchy, used to justify the unjustifiable, remains alive in the disproportionate rates of the imprisonment of people of color.

Yet the sophistry doesn’t fully explain the sadism. Caching up with the visitor is an overpowering sense of white people’s enraged, animalistic treatment of the enslaved and, during Jim Crow, their descendants. It is impossible to take in fully the depth of the savagery. In Colquitt County, Georgia in 1921, John Williams (not his real name) refused to admit whatever he was being accused of. As he was burned alive, he sang “Nearer My God To Thee.” In Tattnall County, Georgia in 1907, when they lynched Sam Padgett, they also lynched his 10-year-old daughter, Dosia. In June 1879, in Henry County, Kentucky, they lynched two girls, age three and ten. No one bothered to record their names. In all 6,500 were murdered in this way between 1865 in 1950.

Yet the sophistry doesn’t fully explain the sadism. Caching up with the visitor is an overpowering sense of white people’s enraged, animalistic treatment of the enslaved and, during Jim Crow, their descendants. It is impossible to take in fully the depth of the savagery. In Colquitt County, Georgia in 1921, John Williams (not his real name) refused to admit whatever he was being accused of. As he was burned alive, he sang “Nearer My God To Thee.” In Tattnall County, Georgia in 1907, when they lynched Sam Padgett, they also lynched his 10-year-old daughter, Dosia. In June 1879, in Henry County, Kentucky, they lynched two girls, age three and ten. No one bothered to record their names. In all 6,500 were murdered in this way between 1865 in 1950.

A long time ago, Trump might say — and yet our animalistic urges remain. When conference attendees gathered Wednesday evening in small discussion groups to talk about the day’s experience, I chose the group of those drawn to the word “challenge.” I felt challenged by the correlation between the lynching headlines preserved in the museum and the headlines in the paper today. Examples are separating immigrant families, sending Venezuelans to torture prisons in El Salvador, a grand presidential tour of a Florida immigrants’ prison called Alligator Alcatraz, knocking down the doors of immigrant workers of color and their families and detaining them without probable cause thanks to the Kavanaugh rule, slaughtering 130 men of color on the high seas just to watch them die, depriving Africans and their children of life-saving medicine without saving any money, sickening racist attacks against our Somalian neighbors, slamming the door in the face of refugees of color while admitting Afrikaners, and a blood libel about our Haitian neighbors eating our house pets followed by a threat to send a third of a million back to chaos-riven Haiti.

A long time ago, Trump might say — and yet our animalistic urges remain. When conference attendees gathered Wednesday evening in small discussion groups to talk about the day’s experience, I chose the group of those drawn to the word “challenge.” I felt challenged by the correlation between the lynching headlines preserved in the museum and the headlines in the paper today. Examples are separating immigrant families, sending Venezuelans to torture prisons in El Salvador, a grand presidential tour of a Florida immigrants’ prison called Alligator Alcatraz, knocking down the doors of immigrant workers of color and their families and detaining them without probable cause thanks to the Kavanaugh rule, slaughtering 130 men of color on the high seas just to watch them die, depriving Africans and their children of life-saving medicine without saving any money, sickening racist attacks against our Somalian neighbors, slamming the door in the face of refugees of color while admitting Afrikaners, and a blood libel about our Haitian neighbors eating our house pets followed by a threat to send a third of a million back to chaos-riven Haiti.

It’s not just about immigration policy. We could secure the border without cruelty for cruelty’s sake or rhetoric about vermin and polluted blood lines. Trump and his operatives are treating people of color with determined inhumanity and desensitizing the public to racial violence. Unless decent leaders use every possible constitutional means to stop them, one day there will be a museum about it, and those who were complicit will have a wing to themselves.

It’s not just about immigration policy. We could secure the border without cruelty for cruelty’s sake or rhetoric about vermin and polluted blood lines. Trump and his operatives are treating people of color with determined inhumanity and desensitizing the public to racial violence. Unless decent leaders use every possible constitutional means to stop them, one day there will be a museum about it, and those who were complicit will have a wing to themselves.