“In my father’s house, there are many dwelling places.” In our earthly houses, there are many ways to be a father. And under the job description for father, which is to say for any parent, appear an endless number of boxes to check.

“In my father’s house, there are many dwelling places.” In our earthly houses, there are many ways to be a father. And under the job description for father, which is to say for any parent, appear an endless number of boxes to check.So too with bishops. This morning the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles bids au revoir to an overseer and a leader, a brilliant teacher, pastor, and prophet. With all that, there’s also a lot of patriarchy packed into this ancient office. It will be here for a while yet. Bishops, deacons, and priests of all genders grapple with it – deconstructing it when they can, living with it when they have to, making the best of it for God’s glory in their own innovative ways.

But it can come roaring back at moments like this. Celebrating the life of someone such as Chet Talton, celebrating this finest of bishops, the family metaphor comes down around us handsomely, like the winter rain.

After all, we have the word of God itself. “I will be their God,” we hear the creator say in Revelation, “and they will be my children.” Chet Talton was both devoted father and church paterfamilias. Karen and April; Kathy, Linda, Fred, and Ben; this beautiful cohort of grandchildren — his generous family lent him to us.

He construed his vocation in family terms. He said he wanted to be present to people, to acknowledge people, to see people. He said he wanted to make life more human — and for better or for worse, the wellsprings of our humanity are our families. We claim him for our family, because he claimed the church as part of his. The church enabled Chet Talton to work on his project of improving humanity’s prospects while filling the places in his heart that his family of origin had left temporarily vacant.

This was an awful year for Chet and April. Their beloved dog Buddy died. The January fires didn’t destroy their home in Altadena but damaged it enough that they were refugees for several months. They depended on the kindness of family and Airbnb. They’d barely been home a few weeks when a series of health setbacks came down, beginning with Chet’s back injury as he puttered around the house.

Bishop Ed Little and I visited and ministered. One afternoon at Huntington Hospital, though Chet was in considerable discomfort, he and I found ourselves talking about our fathers. Chet had a wonderful mom and a cordial relationship with his stepfather. His father hadn’t been part of his life growing up. He had longed for it to be otherwise.

Chet was an adult when a meeting was finally arranged in Detroit, where his father was living – my hometown as well. But it didn’t last long. Less than an hour. It wasn’t a movie happy ending. Proximity did not make two hearts grow closer. It was all his father was able to give. But it hurt. All these years later, the lost opportunity for reconciliation still hurt.

Pastor that Chet was, smiling through his pain, he listened attentively to my story, which has similarities to his which need not distract us. As we finished, he drew my attention to the last page of his book with Malcolm Boyd, “Race and Prayer.” This is where we read some of the famous story of the Rev. Lewis Baskerville, rector of St. Augustine’s in Oakland, the great uncle of one of our ministers of ceremonies, Canon Suzanne.

His parish happened to be across the street from the Taltons’ home. Lewis happened to be the kind of man and priest we do know from novel and legend, who gave a thirsty 11-year-old boy wellsprings from which to drink at last. A new measure of self-regard as a young man of African descent in a racist community. A model for how to be a good man in a sometimes cruel world.

Chet wrote, “He acknowledged me as adults seldom do with children.” This priest acknowledged Chet as Chet’s biological father had not done. And Chet eventually decided he wanted to help people as Fr. Lewis had helped him.

If you want to talk about the future of The Episcopal Church; if you want to talk about the kind of bishops, deacons, and priests we need to form; if you if you want talk about the differences we can make in people’s live by mixing the Good News and sacraments with the indispensable family-style ingredients of kindness, curiosity, compassion, connection, and care; if you want to talk about where we get bishops like Chet Talton and the blessing of all he did for the glory of God of the sake of God’s people; preaching at Chet’s ordination, the great Bishop Barbara Harris, nine days after the launching of Desert Storm in 1991, said that Chet would be a bishop singing the Lord’s song in a strange land; if you want talk about the charism our tiny church still has for making our even stranger land safe again for all of God’s people — then we take the story of a not-so-hot father in life and, if you’ll excuse me for indulging the metaphor, a magnificent father at St. Augustine’s, and we ponder in our hearts how it added up for Chet Talton and then for us.

Put those two stories together, and we have ourselves an Episcopal epic. Just follow the archipelago of love that Chet Talton built from Oakland to St. Paul and Chicago, from Wall Street to Harlem – a trail of healed relationships, affordable housing, day care centers, and expanded community outreach. In our diocese, as he worked closely with Bishops Borsch and Bruno, a generation of deacons formed for just his kind of ministry of self-sacrificial love. Cofounding our diocesan credit union, an economic justice ministry to empower and encourage God’s people in a part of our city that commercial lenders had forgotten.

A prophet of justice rarely moved to anger but full of calm indignation when teaching us about arriving at seminary in Berkeley in 1967 and learning that a white classmate got the house whose landlord had said no just two weeks before to him, Karen, Kathy, and Linda. Hearing rectors say in 1970 – not that long ago – that they’d like to hire him as their curate, but their congregation just wasn’t ready.

So when the gay or lesbian person was scapegoated, the trans or non-binary person persecuted, the immigrant worker harassed for their labors, this bishop had been there. As a pastor, he bathed their pain and shame with the balm of empathy. He used his authority and experience to show the scapegoat the way out of the wilderness to their own place of authority and power.

Turned away at the age of nine on account of race when he wanted to be a Cub Scout – by a troop that actually met at an Episcopal parish — he did everything one bishop could to make a better Episcopal Church, and not in just one diocese. I sat next to Chet at an event once and asked him what he planned to do in retirement. He smiled and said maybe St. Augustine’s would take him back a curate. Instead he turned his reconciling spirit and authority to commence a long process of healing in the Diocese of San Joaquin.

Of course, a pastor, and a bishop is mainly a pastor, does almost all their work at ground level. In the weeks since Bishop Talton died, at each congregation I’ve visited, someone has mentioned his kindness when he came to confirm them or their children. Hs soft, old-school tap on the side of the face. The way he modeled strength and gentleness as the prophet and the pastor, the counselor and the friend, the person with authority in the system who used it as a servant does, as Christ commanded.

When Chet’s name comes up, people’s eyes soften, and their smile widens. His integrity, faith, and kindness made the heavenly promises embodied in our liturgies leap from the page into our hearts.

He is part of so many personal and family narratives that the complete story can never be told except in the archives of heaven. As the generations roll, he will have influenced tens of thousands of lives.

He confirmed my daughters Valerie and Lindsay and ordained me a priest, so we celebrate him in our family story.

When Chet baptized their son Stephen on Easter Day at St. Thomas’s in Hacienda Heights, his parents, Tom and Dean Betsy Hooper-Rosebrook, who is participating in our service, noticed how gently Chet’s large hands cradled their baby. When Stephen died at age 29 after falling ill while running an earthly race as a firefighter and paramedic in Bowling Green in 2024, his parents’ hearts flew back to the day Stephen was marked as Christ’s own forever. Chet putting his authority behind the promise of heaven – the likes of Chet having been present for Stephen at the beginning — helped those who loved Stephen trust that his earthly end was another beginning.

Carol Wallace at All Saints Pasadena remembers Chet visiting Transfiguration in Arcadia, where her spouse, Gene, was the rector. It was Christmas Eve, and it had been a long day. After the service, Carol’s son, John, who was eight and full of Christmas energy, wanted to play with Chet’s crozier.

Chet showed John how to take it apart and put it together again. He let John process around the office for a few laps with it. Then Chet looked down at John from what must’ve seemed an immense height, smiled, and said, “You would make a good bishop.”

John did make a good Navy Seal. He served in Iraq and Afghanistan, receiving the Legion of Merit from President Obama while suffering wounds too deep for words. When he got home, the trauma got the better of him, and when he died, it was as though he had fallen on the battlefield.

It was so hard for Carol, and it always will be. But she’ll never forget Chet saying with all his authority that he had confidence in John. That he was a good boy. That’s what a good father says. What a good parent says. By grace, we may believe Chet helped it come true, just as Fr. Baskerville had done.

In other denominations, we have colleagues who take Jesus’s words in the gospel, “No one comes to the Father except through me,” and call it a rule, a requirement to check the Jesus box for entry to the promised land.

But if Jesus came to anticipate every life humans would lead, to bear every sorrow and wound imaginable, then the passage can also mean that no one reaches paradise without experiencing the inevitable agony of a human life and, by the grace of Christ, surviving and receiving extra measures of empathy.

Chet’s early sorrows begat him whom April describes as the strongest, gentlest man she has ever known. Over this last year, she has felt the life she and Chet had been living for two decades being dismantled brick by brick. Every member of his wonderful family must feel as though an irreplaceable light has gone out. He was so proud of them. They love him so much.

Each of us has felt this searing quality of loss and grief at one moment or another in our lives. With his sadness, see what Chet Talton did for the glory of God. See how Fr. Baskerville helped him along. This Christmas, we have this gift of seeing how the gospel magic works. On our journey together to the foot of the holy mountain, see how the spirit of the risen Christ invites each of us to live as Chet did – always helping others, just as we have been helped.

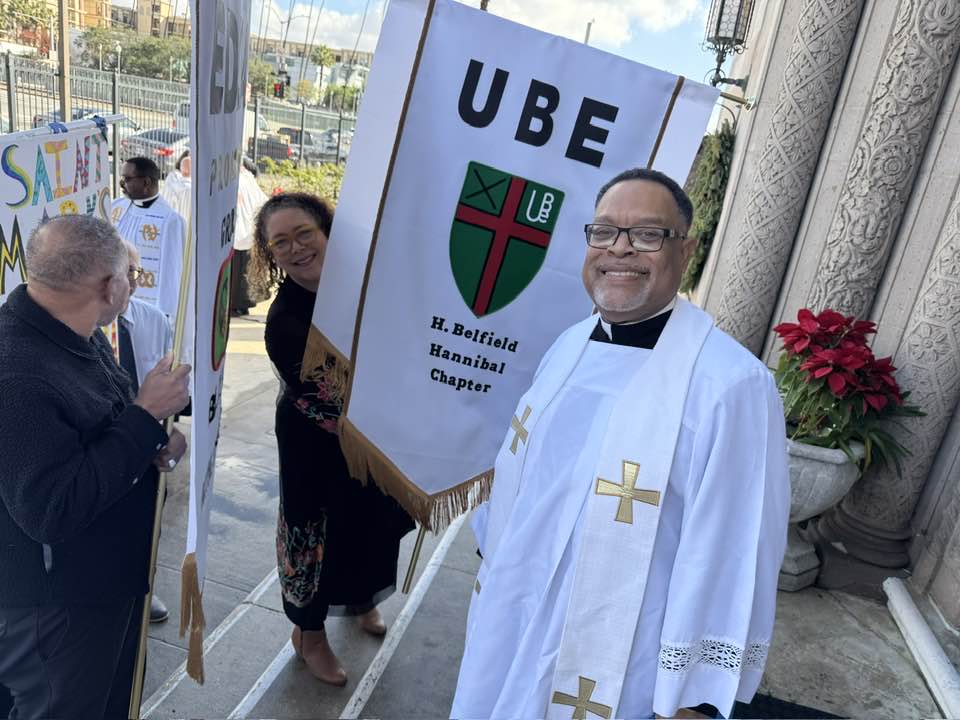

[My homily and album from Saturday’s celebration of life at St. John’s Cathedral for the Rt. Rev. Chester Lovelle Talton, retired bishop suffragan in Los Angeles and bishop provisional in San Jaoquin. Assisting were the Very Rev. Anne Sawyer, the Rev. Canon Jamesetta Hammons, the Rev. Margaret Hudley McCauley, the Very Rev. Betsy Hooper, and the Ven. Canon Carolyn Hakes Bolton. The Rev. Guy Leemhuis and Canon Suzanne Edwards-Acton were ministers of ceremonies. The choir comprised members of the Inner City Youth Orchestra, Dr. Charles Dickerson, founder and conductor, and the St. John’s Choir, Dr. Christopher Gravis, director. The H. Belfield Hannibal Union of Black Episcopalians and the Program Group on Black Ministry hosted a reception after the service.]