If you’re around my age, 70, and you went to summer camp as a child, you probably learned how to weave lanyards out of multicolored strips of plastic. These came in handy whenever you had to hang a whistle around your neck. Since camp officials knew who was paying for the bug juice, they also taught us how make ash trays for mom and dad by pounding squares of aluminum into a wooden mold with a framing hammer.

Then there was the year my fellow campers and I took it up a notch, actually a stairway to heaven of notches, by coming home from Camp Sky Y in Prescott, Arizona with our own handmade Hopi-style katsina dolls. This was the summer of 1968. The hows and whys have been lost to history, or at least the Internet. But helping with arts and crafts that year was Oswald “White Bear” Fredericks, probably the 20th century’s most famous katsina artist as well as the tribal leader who, collaborating with Frank Waters, author of “Book of the Hopi,” did more than anyone to reveal Hopi religion to a general audience.

The first photo shows four of Fredericks’ katsinas from the Barry Goldwater collection at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, dedicated to Indigenous American culture and history. Katsinas, or kachinas, represent all the ancestors and the spirits of the natural world. Most are made from lengths of cottonwood root. Goldwater, who fell in love with Hopi culture as a boy, gave his collection of over 400 katsinas to the Heard in 1964, the year he ran for president.

It includes nearly 100 figures that Goldwater commissioned from Fredericks. My mind still boggles that, at age 13, I sat at the knee of the Stradivarius of his art form. He would carve the wood and help us use feathers and beads for the features and decoration. I assume I was a grave disappointment. He, too, perhaps. I remember my mother saying at the time that he was on the outs with other tribal leaders for helping Waters. A consensus on his historical legacy remains elusive. Yet “Book of the Hopi” remains in print as a popular choice for those attempting to understand complex Hopi cosmology.

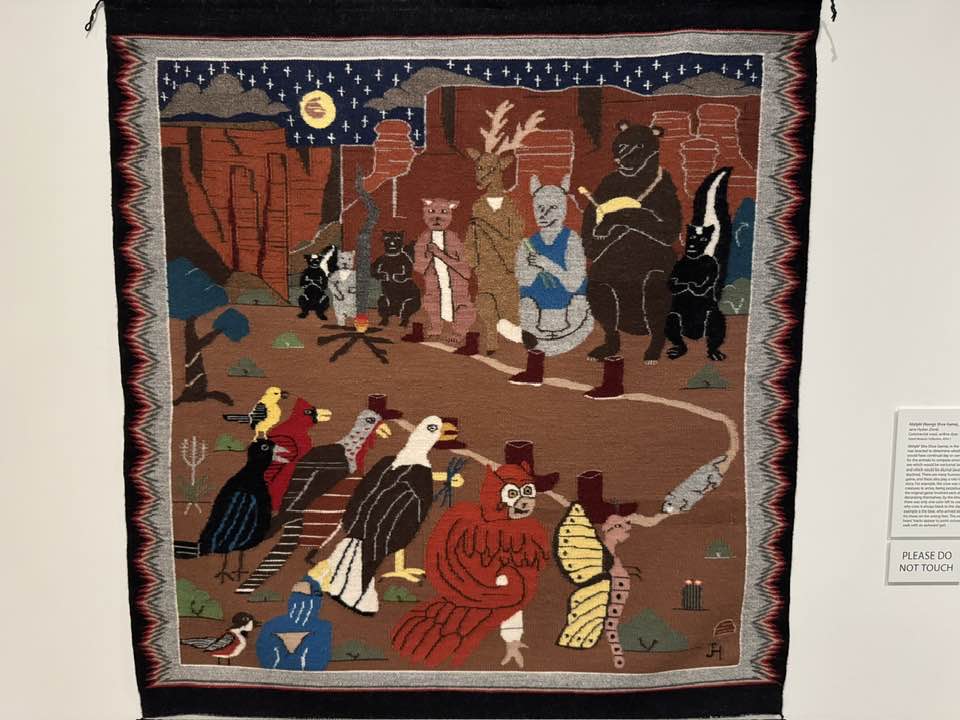

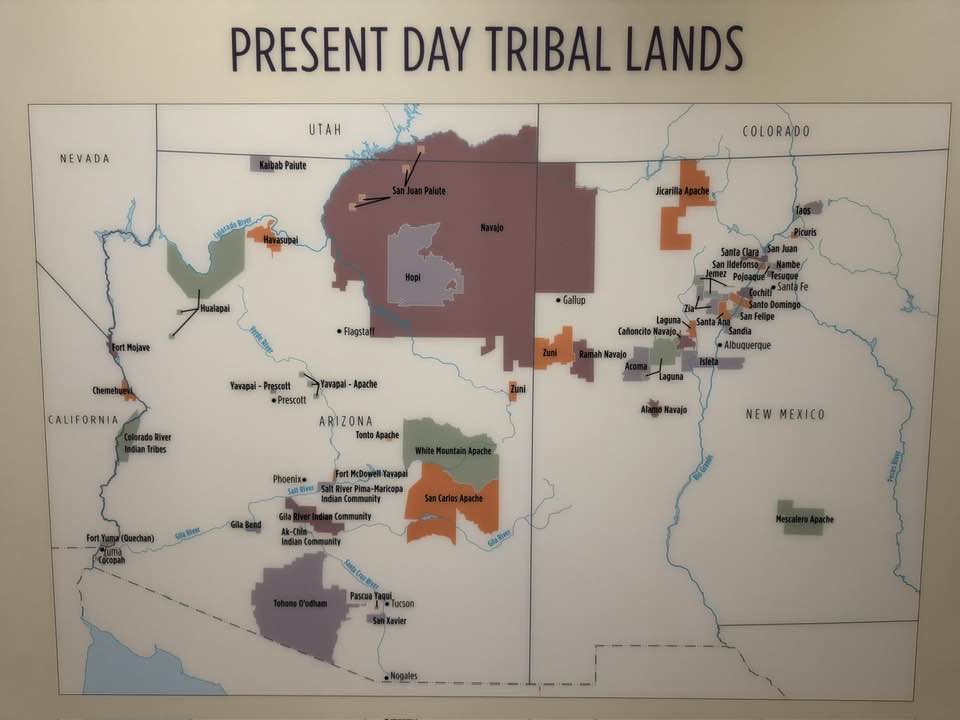

I spent over two hours today with the Heard’s exhibits on the Indigenous Americans of Arizona and New Mexico, including at the ancient Acoma Pueblo, which I visited last summer. These are places where people have been living continuously for at least 1000 years. The Pueblo nations’ late-17th century revolt against the Spanish is considered the first American revolution.

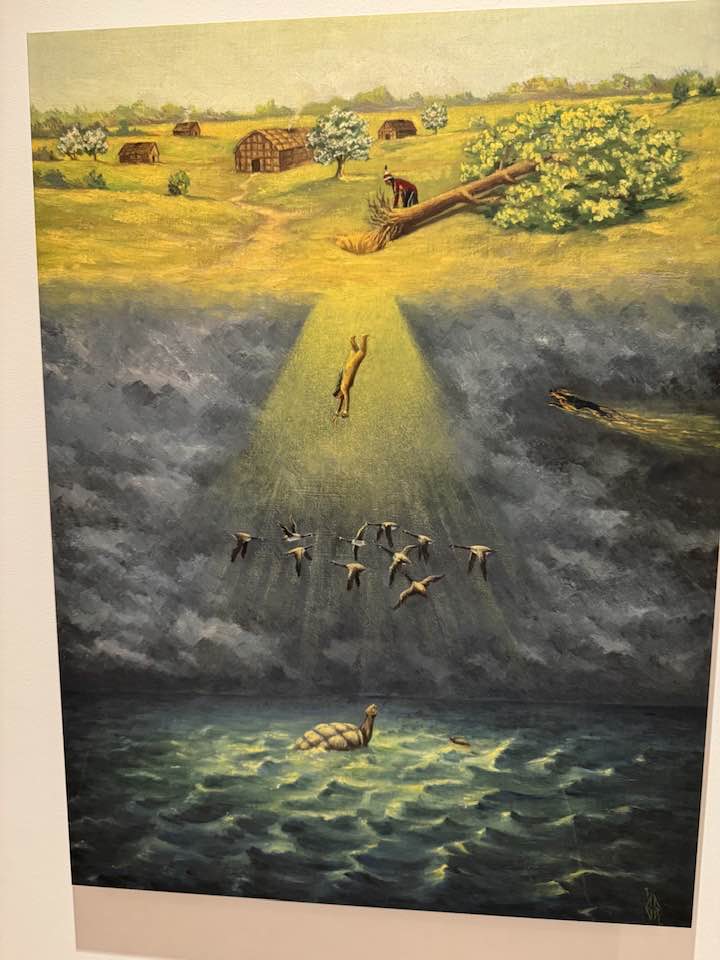

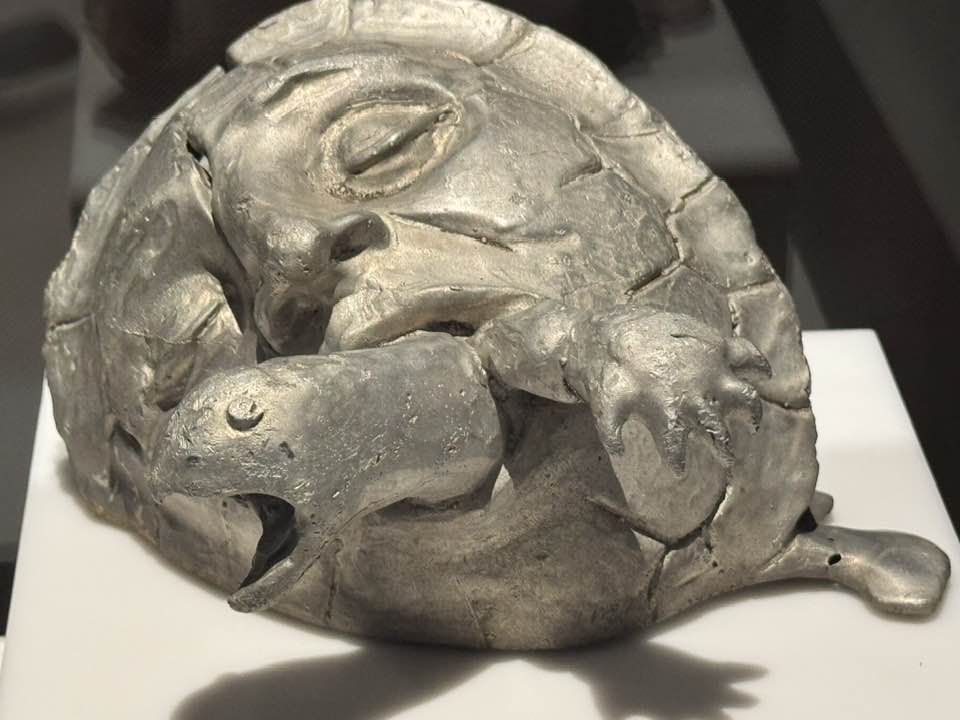

Los Angeles-born Warm Springs Chiricahua Apache artist Bob Haozous, who astonishes in virtually every medium, has a major retrospective. The earth’s degradation is his great preoccupation. Some native American cultures envision North America as a turtle on whose back the creator settled creation. Look for his small sculpture of the turtle crying out in agony.

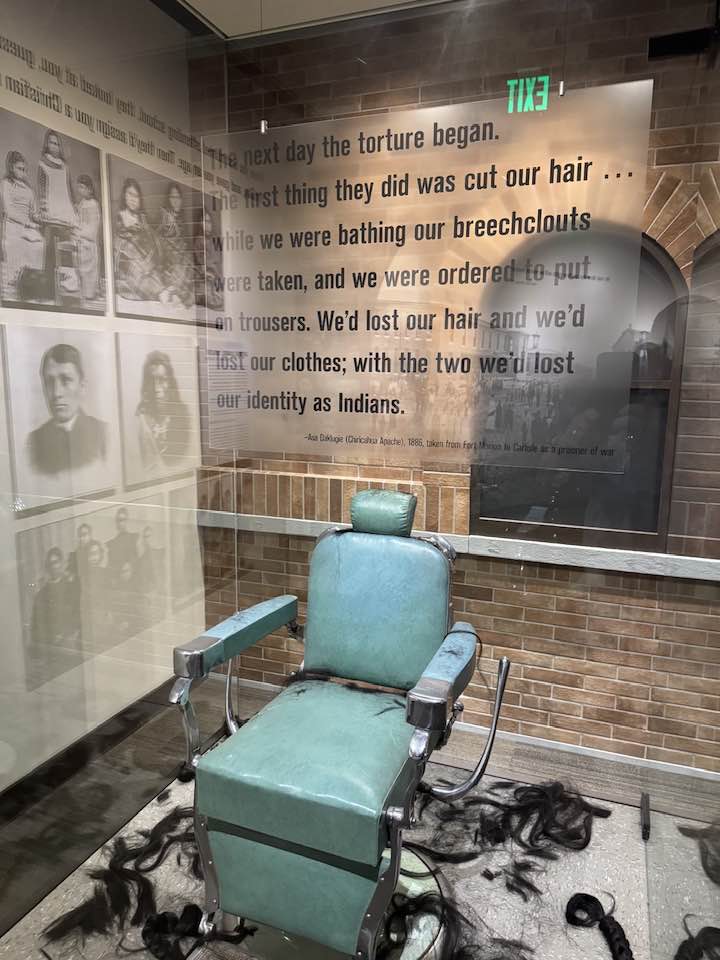

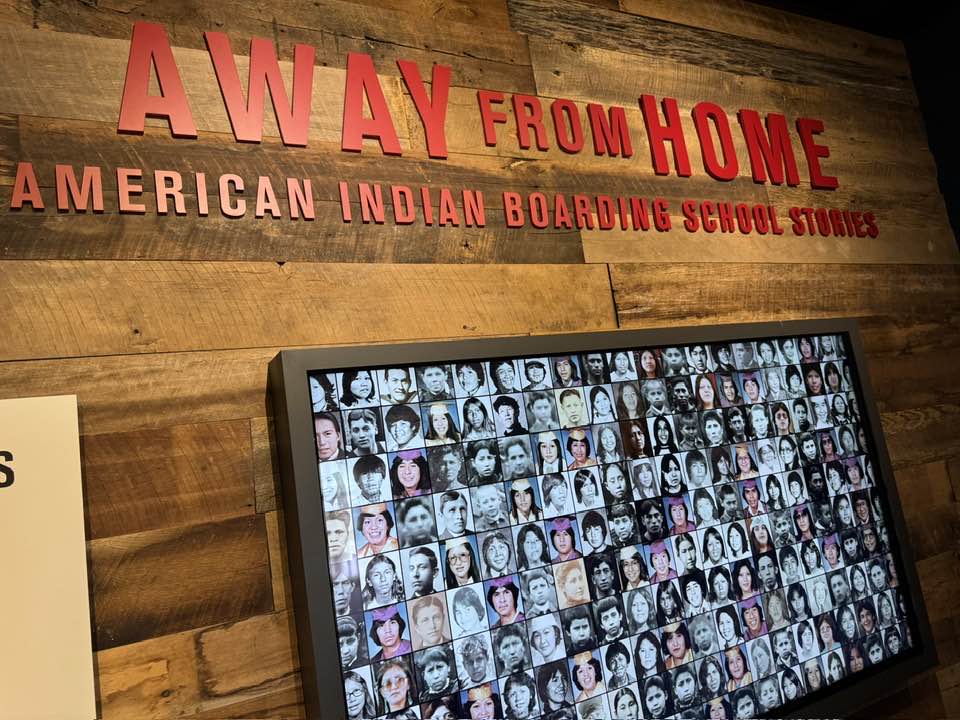

The Heard’s recently updated permanent installation on the United States’ Indian boarding schools is heartbreaking. Imagine the federal government deciding to eradicate a culture by trying to brainwash its children. Look at students’ sorrowful faces after their mandatory haircuts, when they were forced to wear white people’s clothes and forbidden to speak their own languages. From the very beginning of this oppression and abuse, the young people resisted courageously.

My old boss Mr. Nixon gets some props here. In 1970, working with the late Leonard Garment, one of his White House advisors, he called for an end to the prevailing assimilationist policy in favor of one based on tribal self-determination. Congress passed legislation embodying the shift in 1975, the year after his resignation. This is one reason many of our Indigenous American siblings have more successful casinos than Trump. The U.S. Bureau of Indian Education oversees nearly 190 schools in 23 states according to the new principles. Better late than never — and yet so much atoning to do, in memory of the spirits of the ancestors.