As epiphanies go, Thomas Merton’s in downtown Louisville nearly 80 years ago was one of the best. Looking at the crowds on the sidewalks, he said, “I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers.” He said he saw them for a moment as their creator did, saw deeper in their hearts than even they did.

He saw their hearts’ secret beauty. All beloved of God. All made in the image of God. So all worth knowing intimately. And this was Kentucky in 1958. He was looking at all sorts and conditions of people. Racists and radicals, saints and sinners, Republicans, Democrats, and Dixiecrats. People off to buy anniversary presents. People who had lied and cheated at work or were on the way to betray their spouses. People who were thinking about sex or death or listening in their heads as they walked along to “Sweet Little Sixteen” by Chuck Berry or “All I Have To Do Is Dream” by the Everly Brothers.

To know what they were up to, you would have to ask. Just because of who they were, children of God, the answer would always be worth knowing. The theology of Merton’s epiphany is that every human being is of infinite interest. I wouldn’t exactly say I have epiphany envy. I can behave like this whenever I want. Or not. The first two pictures below are selfies of me with people I didn’t talk to on my vacation trip, having breakfast in Boulder City and walking along Fremont Street in Las Vegas, where four bands were playing on Saturday night, including Dr. Rock. Vegas is the most diverse setting one can imagine. Think of the political conversations alone. I’ve no doubt they would’ve Dr. Rocked this never Trumper’s world.

I’m more reticent than you might think about striking up conversations with strangers. I have a childhood fear of being thought weird or an imposition. Also, my annual driving trip is as close as I come to a silent retreat. I’m not working. I’m driving. But visiting our Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles parishes and missions, I can’t get enough. I want to know how long people of been worshiping there and what they’re passionate about. I wouldn’t be afraid to ask, “So dude, what’s with the Pablo Escobar T-shirt?” or compare notes on how we take our coffee.

Congregational life, it seems to me, is an opportunity for almost infinite exploration along Merton epiphany lines. Eighty percent of parish ministry is asking and listening, since people’s answers reveal context, passion, pain, and hope. When we ask, listen, and learn, we plant the seeds of mutually supportive communities of connection and care that, if they proliferated, would cure a good deal of what ails us as a society. It’s a canard that we only use a small percentage of our brains. But I guarantee you that we use a minuscule portion of our curiosity. “There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun,” Merton said. And there is no way of telling all the light we could cast by abandoning our reticence, fear, and selfishness about other people.

I’ve made a couple friends along the way. On Sunday, I abandoned the 40 east of Kingman and took Route 66 through Hackberry, Valentine, Truxton, Peach Springs, and Seligman. In Antares Point, at a place called Kozy Corner, check out the old cars and the giant green tiki head. Inside, Al let me use the rest room. I bought an ice cream and a cap. He asked about my bishop’s ring. He was passing the time with a word search book based on scripture readings. He said he and his wife do it together in the evening.

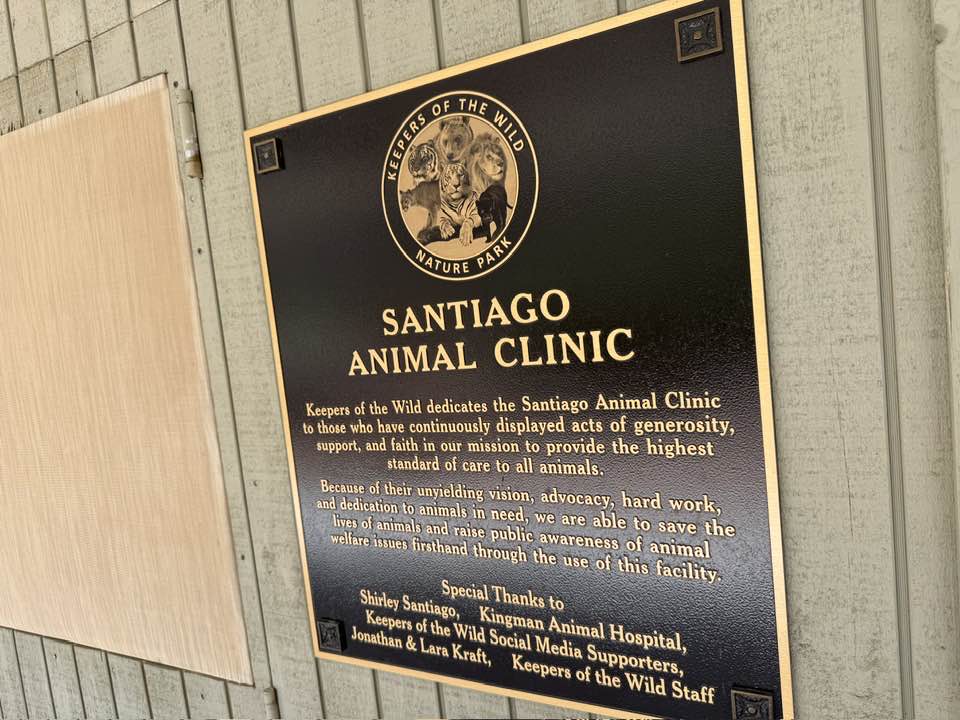

Another irresistible roadside attraction was Keepers of the Wild Nature Park. Lisa and Sparky greeted me and said it was established 30 years ago as a nonprofit to care for animals left homeless by fire or neglected, mistreated, or abandoned by their owners. They have 175 acres of tigers, bears, emus, and hundreds more. I felt a little guilty not taking it all in. The midday heat prevented me from making too many more new friends. Coming back into the office, I apologized, blaming the advancing years. I made up for it in the gift shop. Membership in the people pleasers club has its rewards. Skippy gave me a free shopping bag, Lisa a beautiful Keepers of the Wild wall calendar.

Most people want to be the tourist folks remember fondly. Merton’s epiphany eyes come in handy on the road. Everyone we meet has an encyclopedia of a story. Here at the Grand Canyon, one table server asked me where I was from. He said he was from Cuba via Puerto Rico. I would’ve love to hear that whole deal, but he had eight tables. You also don’t know what strangers have experienced. Another server introduced herself so softly and reticently, retracting her head a few inches as she spoke, that I wanted to lower my voice in response. She offered me God’s blessing when she presented the check.

Merton’s epiphany eyes have x-ray vision. They see the people we don’t even meet. When we leave a hotel room, we can throw our towels on the floor, or we can put them on the counter, so no one has to bend over and pick them up. Making all those beds, they have an aching back. Or we may decide to offer our pronouns when introducing ourselves to an audience. Some Democrats are staking their recovery on abhorring such woke things. But Merton’s epiphany eyes see the person in the crowd we may never know who feels that we have acknowledged their shining sun of an infinitely interesting and priceless reality. Along the way, I’m rereading Michael Connelly’s Bosch novels. “Everyone counts,” LA’s favorite sleuth says, “or no one does.” I wonder if Harry Bosch knew Thomas Merton.