Chuck Berry was behind bars when he wrote “The Promised Land,” one of our greatest songs about the liberating power of the open road. In the early sixties, he served 18 months for violating the Mann Act. The charges involved a 14-year-old girl he met and befriended in Mexico who, he said, looked older. His conviction was clouded by the Mann Act’s racist roots, an 82-year-old district court judge’s racism and palpable contempt for the guitarist and singer, and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s phobias about interracial sex, which drove the investigation. Berry always denied the charges. The young woman did not. Though admiring of his subject, Berry biographer RJ Smith does not argue that it was an undeserved rap.

After appeals, Barry did his time. And one day in federal prison in Springfield, Missouri, using a guitar his family had sent him, he sat down and wrote, “I left my home in Norfolk, Virginia, California on my mind,” beginning the story of a great American odyssey.

The narrator, our hero, calls himself the poor boy. The first part of his trip is touch and go, since it’s all in the south. The listener is thinking about the experience of people of African descent in Jim Crow times, including Berry himself. We especially worry when the bus breaks down in cruelly segregated Birmingham. But the spirit is with him. He buys a train ticket and gets safely through Mississippi to New Orleans. Friends in Houston buy him a silk suit and luggage and a ticket on a 707 to Los Angeles, where he picks up a phone in the terminal and tells the operator: “Tell the folks back home the promised land’s calling, and the poor boy’s on the line.”

You may know Elvis’s version better than Berry’s. Like many of his generation, Elvis pronounces it Los “Angle-is” when talking to the operator about the phone call to Virginia. The Grateful Dead also had it in their set for many years. Balladeer Dave Alvin puts it at the end of a brilliant medley, beginning with his and the Blasters’ “Jubilee Train,” about the Depression, into Woody Guthrie’s “Do Re Mi,” about dust bowl-era migrants to California: “Believe it or not/You won’t find it so hot/If you ain’t got that dough re mi.”

In sudden contrast with the economic gloom and doom, Alvin and his band swinging into “The Promised Land” is exhilarating. But Alvin is swinging for the cycle. We still have so much work to do. Right after the poor boy’s LAX phone call, Barry’s triumphant proclamation of the irresistible lure of the American dream, Alvin’s band goes quiet again. A harmonica wails like a train whistle. Alvin takes the listener back to the beginning, his song about scarcity, promise, and hope:

There’s a young boy on the side of the tracks

Alone with a flag in his hand

He heard the train pass by years ago

He’s waiting for a Jubilee train

The young boy is the poor boy is all of us, whatever we fear and hope. As my annual southwest driving trip nears its end, I’m pretty clear about what I’m looking for. It’s freedom just for a while to go where I will, more or less, awakening for a few mornings in a row to practically infinite possibility. It is also always good to remember the vastness of the country I love as well as the fullness of our union’s perfectibility, so that all might enjoy the privilege that has helped make my trip around my beloved southwestern promised land possible.

I’m spending most of my time in Arizona, where my mother and I lived between 1967-71, when she was an editor at the Arizona Republic, then Phoenix’s morning paper. On Tuesday, heading south from the Grand Canyon, like Chuck, I never was a minute late, because I had no particular place to go. I walked along a few Route 66 blocks in downtown Williams, stopping to read the local paper over coffee at Brewed Awakenings Coffee Co. A reporter disclosed that Sen. Mark Kelly had beat me to the El Tovar Hotel at Grand Canyon Village by a few days. He and other officials announced at a press conference that the South Rim was still open for business, even though the Dragon Bravo fire is still burning at the North Rim.

I got to Prescott, the old territorial capital, in time to hear an evening concert in the town square by the Central Arizona Concert Band. One couldn’t imagine a prettier evening, except if Kathy had been there, though I’d be interested in knowing the name of the bugs that began to sing in four-part harmony as the sun went down. No Chuck Berry or Dave Alvin. But they had our toes tapping to a beautifully arranged Stephen Foster medley.

This morning I went looking outside Prescott for Camp Sky-Y, which I attended for two summers during elementary school, becoming a member of the Raggers Society. I got as far as my grey rag, which was not very far. And yet a posted notice outside the dining hall reminded me that, at about age 14, I had pledged “respect and appreciation for Christ’s principles, the world, our country, our fellow man, and oneself.” Speaking of perfectibility, I am still working on some of that. Numbers fixed to a beam above the dining hall porch triggered a dim memory of lining up before meals by cabin or group number. All the cabins have been rebuilt. An historical cabin was preserved, no doubt for the sake of selfies with historical campers.

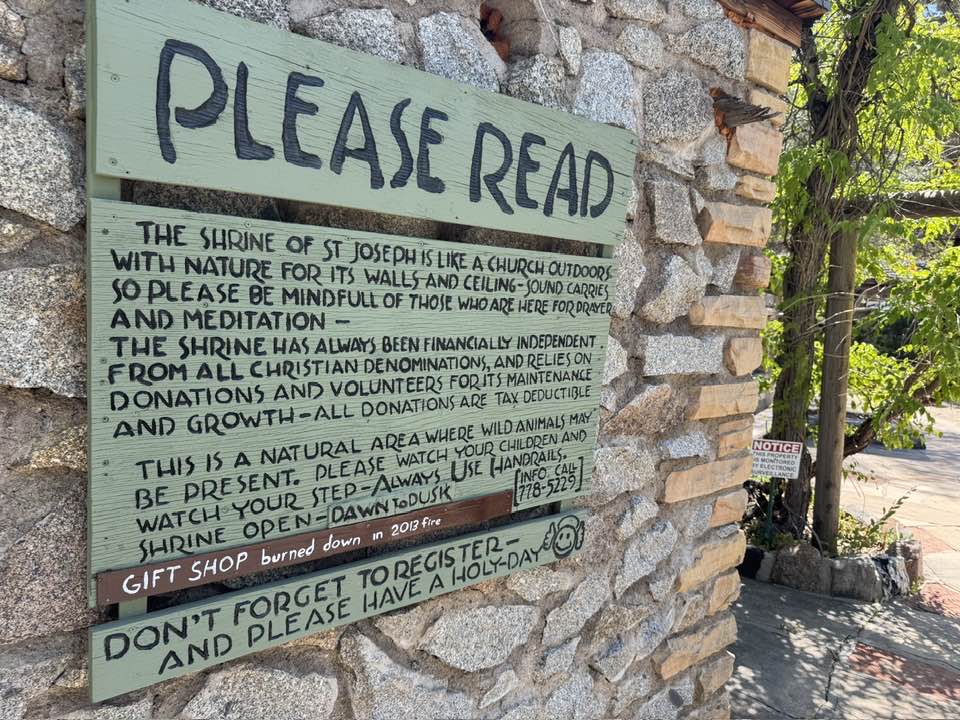

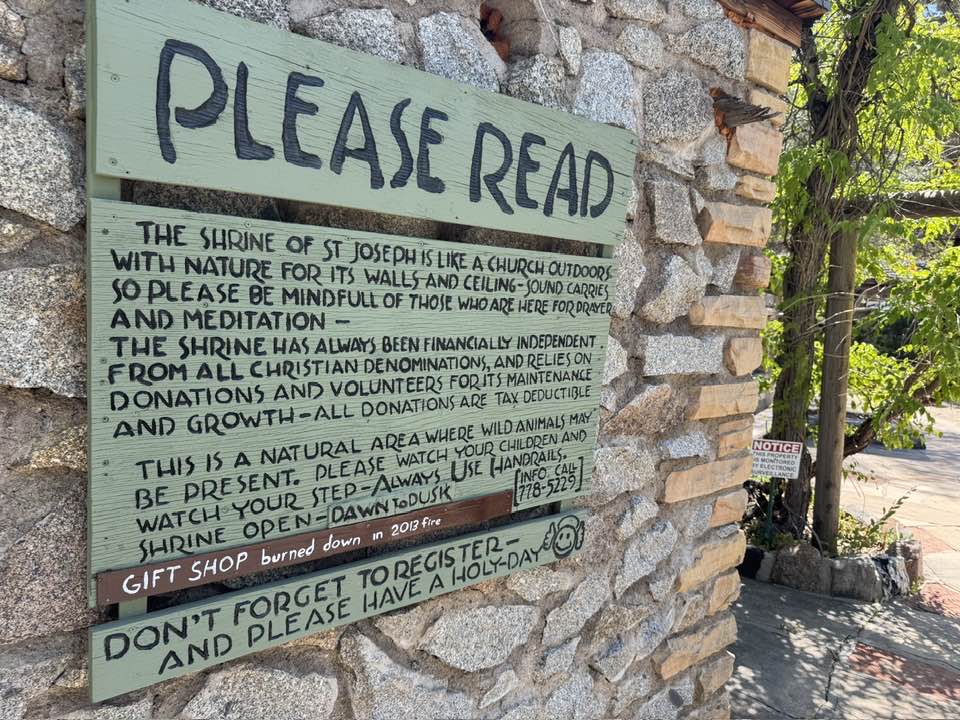

As I set my face for Phoenix, state route 89 yielded two precious treasures in Yarnell, between Prescott and Wickenburg. If Yarnell doesn’t ring a bell, it will. I was the lone visitor at the non-denominational Shrine of St. Joseph of the Mountains. I didn’t come looking for it. I just try never to miss signs for roadside attractions. Carved into a boulder-strewn hillside, the shrine’s impeccably maintained Stations of the Cross were redolent of the Holy Land.

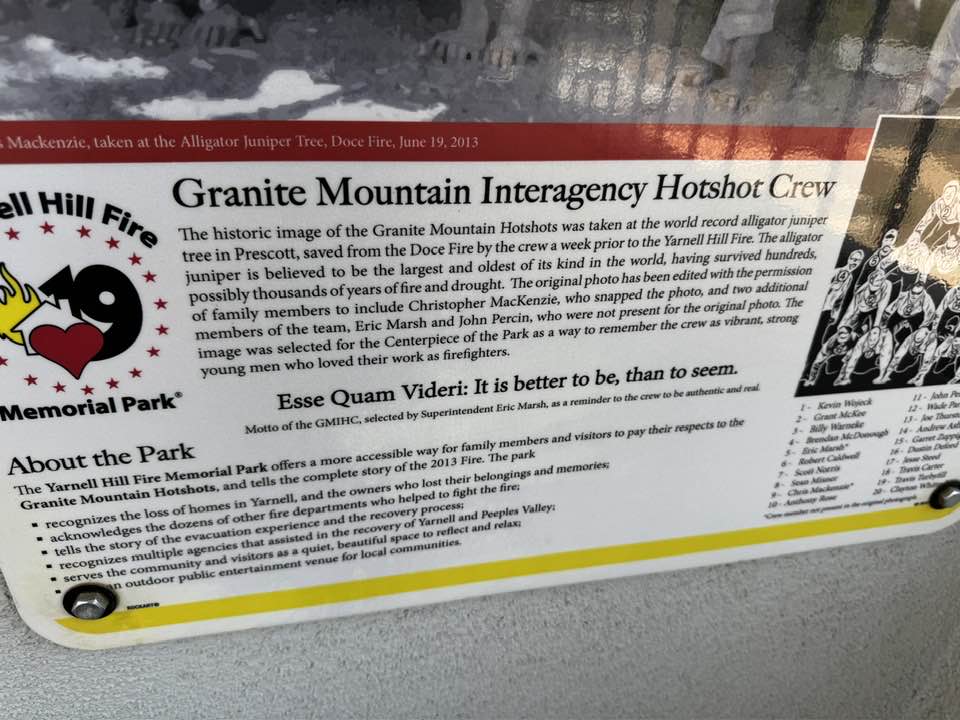

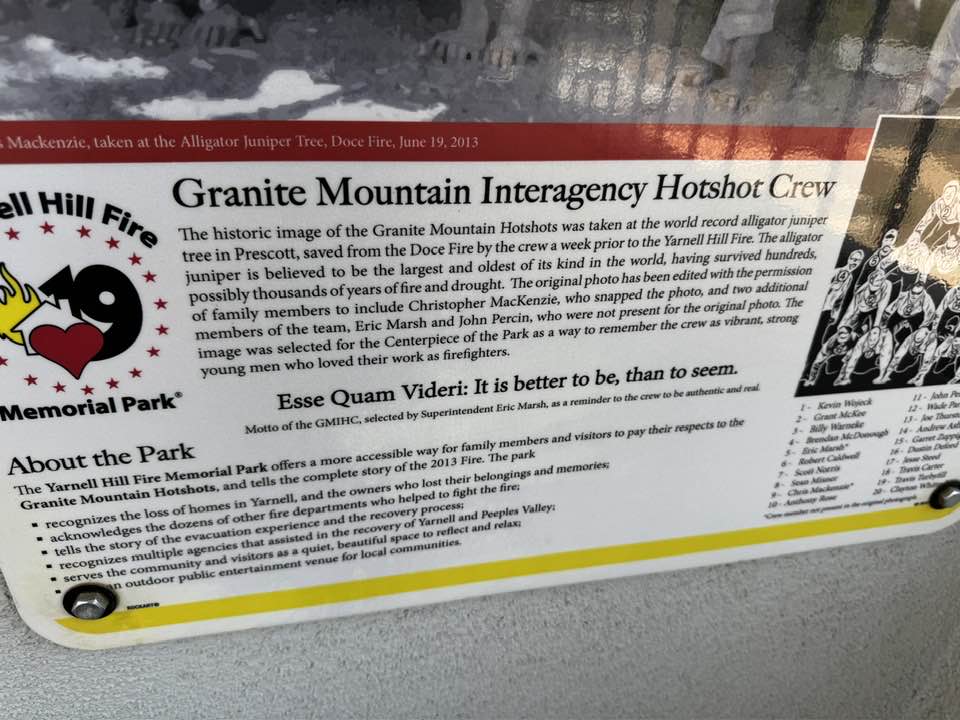

About half a mile away is one of two local monuments to the 19 members of the Granite Mountain Hotshots, out of Prescott, who lost their lives battling the massive Yarnell Hill Fire in 2013. May the promised land be their daily delight and a comforting promise to all who still mourn them.