On the bus on Friday, I told our guests about two sources of violence in American life. Our first stop was St. Gabriel’s Episcopal Church in Monterey Park. They’d of course heard about the mass shooting at a downtown dance studio in January 2023, on the eve of the Lunar New Year. It stunned members of the Chinese diaspora all over the world. The elderly, disgruntled shooter killed 11 and wounded nine before taking his own life.

We drove near the site. I told them the problem was the easy availability of firearms as well as the isolating nature of American life. I said the church of the risen Christ in the U.S. had something to learn from our visitors on both scores. In Taiwan, a free country, it’s almost impossible for most people to own a gun legally. So we can continue to advocate for common sense reform. Taiwan’s Episcopal churches also engage in systematic outreach to their neighborhoods, especially older folks, almost none of whom is Christian. Fewer guns, and more attention to the needs of our neighbors — that’s something to pray for as an antidote against events like Monterey Park.

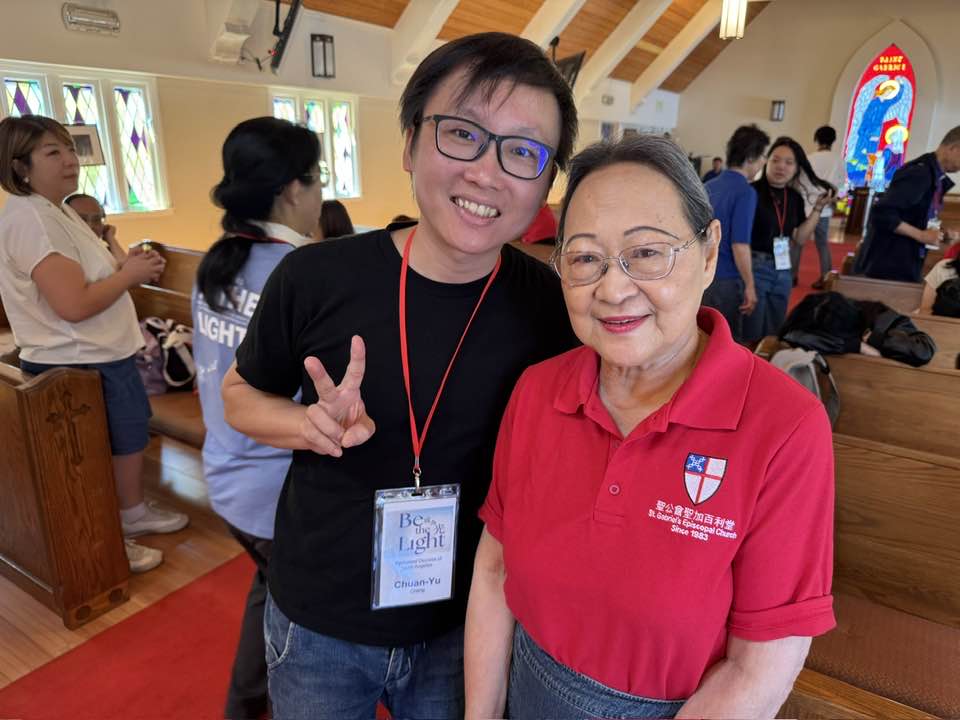

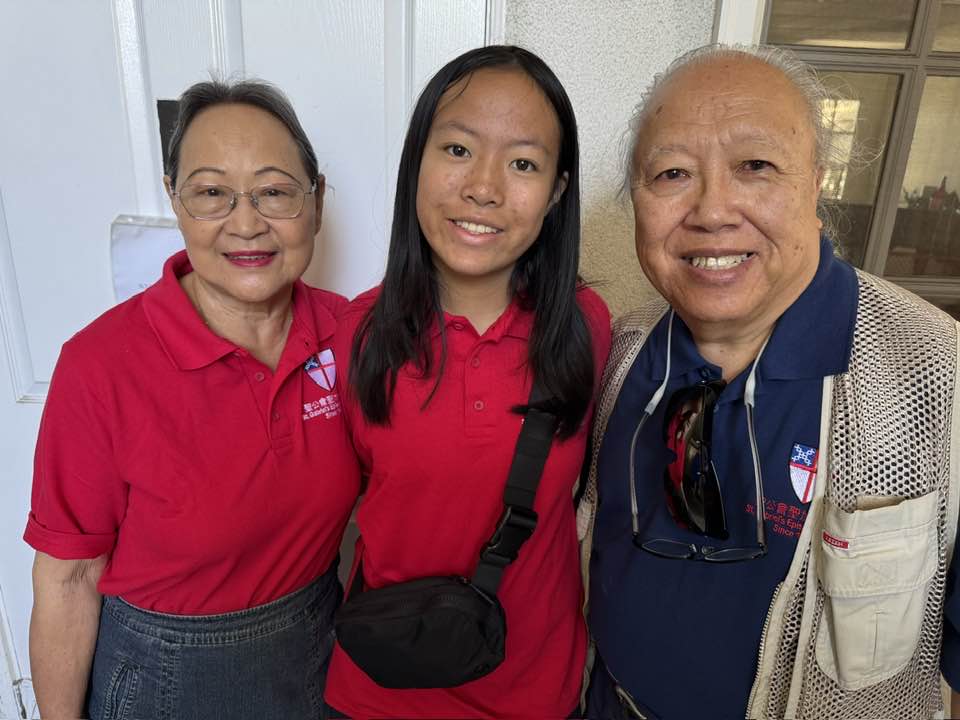

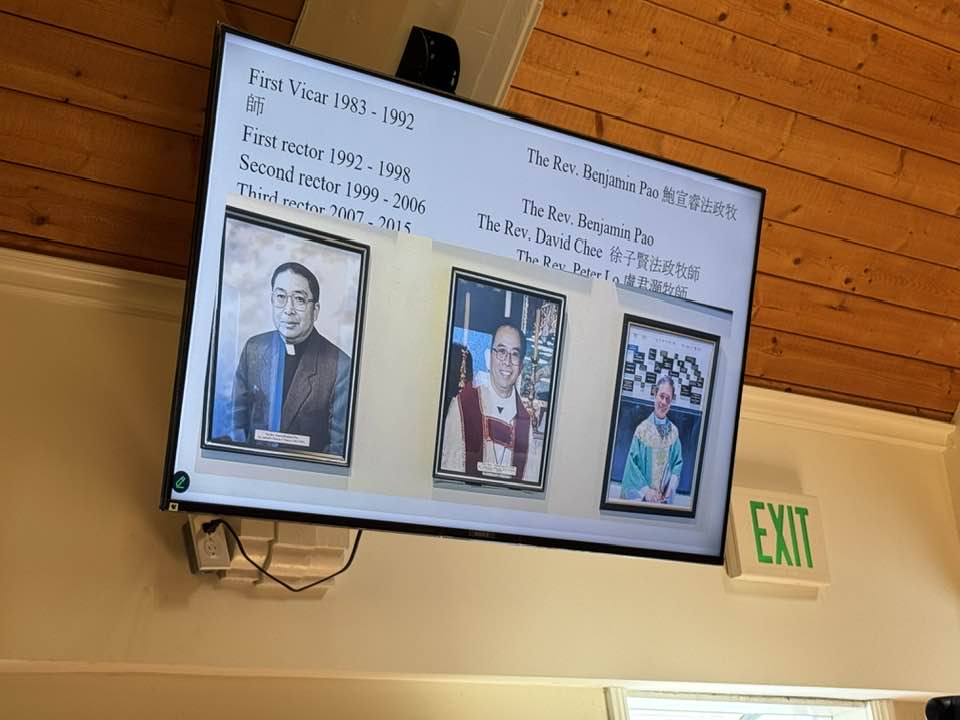

The Rev. Canon Ada Wong-Nagata, priest in charge at St. Gabriel’s, and her devoted lay leaders were wonderful hosts all morning. For over 30 years a neonatal ICU nurse at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles, Canon Ada is an exemplar of Christian love. She was both baptized and married at St. Gabriel’s. Our diocese lagged in Chinese language ministry until the early eighties, when Bishop Robert Rusack lured the Rev. Benjamin Pao from Boston. Fr. Pao said he would only come if he had his own church. So declining Holy Spirit in Monterey Park became ascending St. Gabriel’s, named for the archangel as herald of something new in the city of angels. Volunteers renovated the church and raised money for the beautiful stained glass window at the rear of the nave.

The parish’s tradition of strong lay leadership continues. Canon Ada lives in northern California and helps care for her and her spouse Ronnie’s two adorable grandchildren, so she can’t be present every Sunday. Her team includes guest preachers and lay presiders, teachers, and preachers. As she showed us around the grounds, including the beautifully maintained desert landscaping and the classroom building built by another longtime former rector, the Rev. Canon David Chee, ideas for shared ministry and exchanges abounded in our conversations with Bishop Chang and his colleagues. He and Canon Ada promised to be in touch.

After a magnificent St. Gabriel’s-hosted dim sum lunch in Monterey Park, we headed for Homeboy Industries near downtown Los Angeles, possibly the largest gang intervention and rehabilitation organization in the world, founded in 1992 by Fr. Greg Boyle. So my work on the bus was unpacking “gang violence.” Our visitors already knew about the U.S.’s persistent unkindness to cohorts of immigrant workers, especially from China, now from Central America and Mexico. Parents working multiple jobs (employers saying “stay”) while dodging la migra (opportunistic politicians, promoted by some of those same employers, saying “leave”) are less well equipped than more privileged neighbors to provide impressionable young people with nannies, babysitters, and well-funded after-school care programs.

For many, gangs fill the vacuum. Anthony, our guide, joined one and, at 15, was tried as an adult for attempted murder. Homeboy assisted his transition after his 20 years in state prison. He showed us the enterprises where interns learn skills to list on their resumes, the tattoo removal clinic, and rooms where vital group therapy occurs. At first, Anthony said, it was hard to talk about the violence he experienced in the projects and prison. “But then I began to realize I wasn’t by myself,” he said. “We support one another’s healing journeys.” Our visitors listened with their usual care, making notes on their telephones, asking questions, and posting detailed summaries on-line.

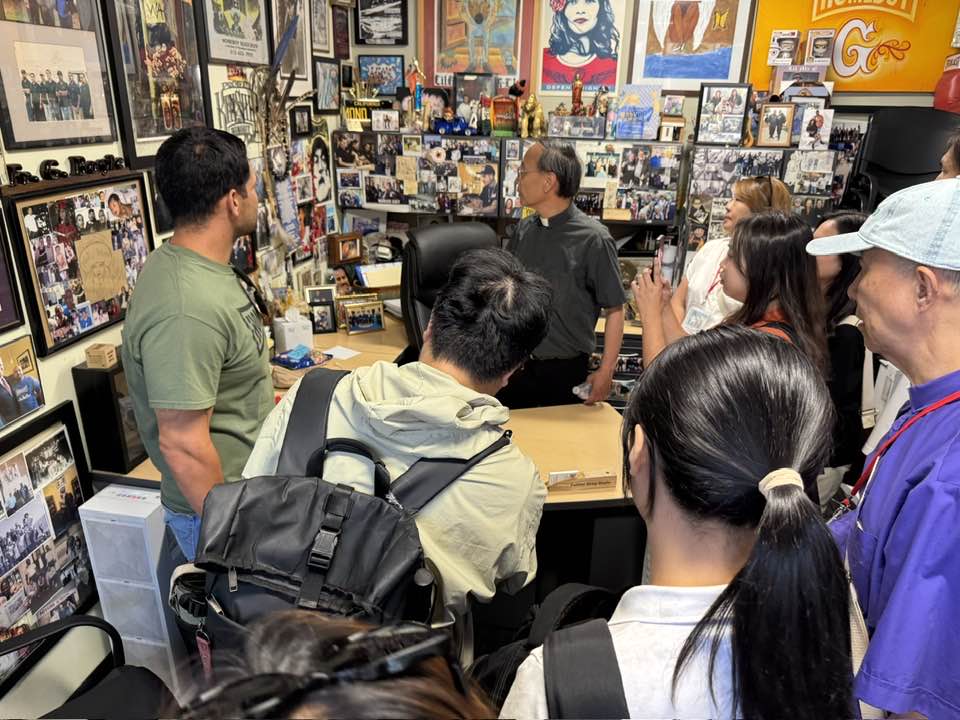

If you’ve never been to Homeboy, it’s as friendly as coffee hour after church. Everybody wants to welcome you and say hello. I have been to places where I have sensed the active presence of abandonment and evil. At Homeboy, one feels the spirit of the living God of love. Fr. Greg was away at a conference, and so we could only gaze through glass at his office, filled with photographs and other treasures. Seeing us, one of the Homeboy staff members, a former gang member like all of them, unlocked the door, and we flooded in, feeling radically welcomed.

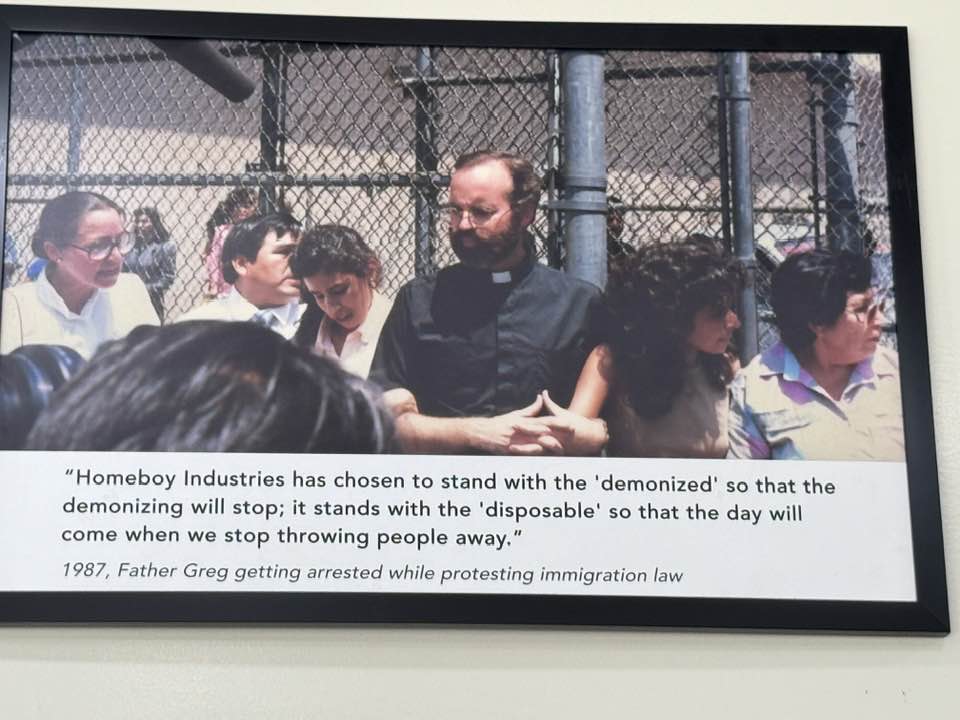

A picture on the lobby wall shows Fr. Greg getting arrested at an immigration protest in 1987. This is his quotation in the caption: “Homeboy Industries has chosen to stand with the ‘demonized’ so that the demonizing will stop; it stands with the ‘disposable’ so that the day will come when we stop throwing people away.” I felt sad talking about things in the U.S. that aren’t going so well. I was proud that Canon Ada’s and Fr. Greg’s fellow laborers from Taiwan also saw us at our best.