When I visited St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, Long Beach on-line last October and met with the vestry, we talked about how a parish known for its activism was contending with a pandemic that was hitting hardest among its unhoused neighbors and neighbors of color. How had they kept glorifying God and caring for God’s people while making sure everyone was safe? “Prudently,” the senior warden said, “we threw caution to the wind.”

Back at St. Luke’s in person Sunday to celebrate and preach as it honored its patron with a lovely bilingual service, I beheld some of the results of prudent institutional abandon. About 125 of us were present as 20 were confirmed. Led in procession by mariachis after church, we made eight stops where, all told, $500,000 was recently invested in improvements to the campus’s public areas.

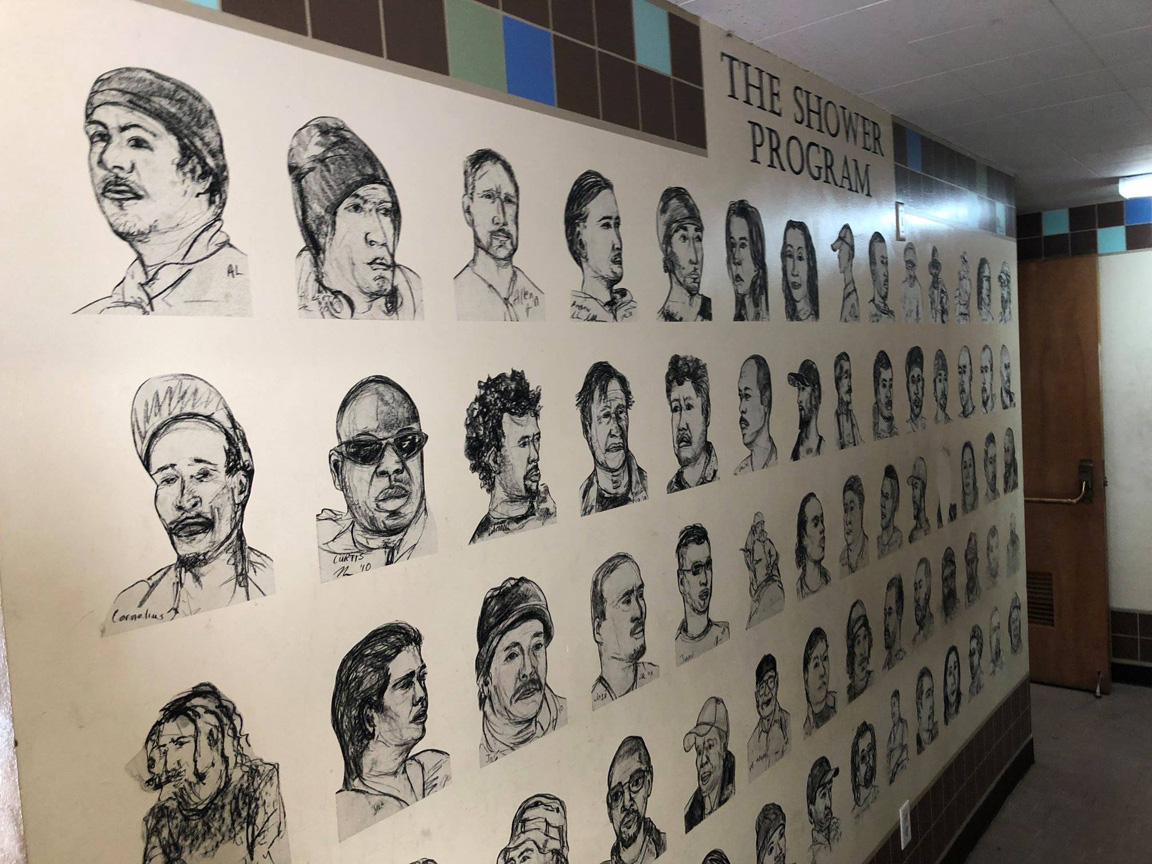

A new, more accessible sanctuary. Laundry machines and water heaters for the legendary Saturday shower program for the housing insecure, which didn’t pause once for COVID-19. A renovated parish hall and the Rev. Canon Gary Commins conference room. All made possible by donors to the St. Luke’s capital campaign as well as by The Ahmanson Foundation, Long Beach Community Foundation, and United Thank Offering.

Among those confirmed or received were shower program clients as well as volunteers, Roman Catholics, Methodists, and evangelicals, and several who’d found St. Luke’s during the pandemic, when it excelled at live-streamed worship. When I met with them before church, they said they’d felt at home because of the parish’s spirit of welcome and its example of a community living out its proclaimed gospel principles of justice and love. During my earlier meeting with wardens Ryan Mascorro Blazer and Brad Neumann and the vestry, these devoted lay leaders described spending pandemic months studying and addressing white supremacy in society and the church.

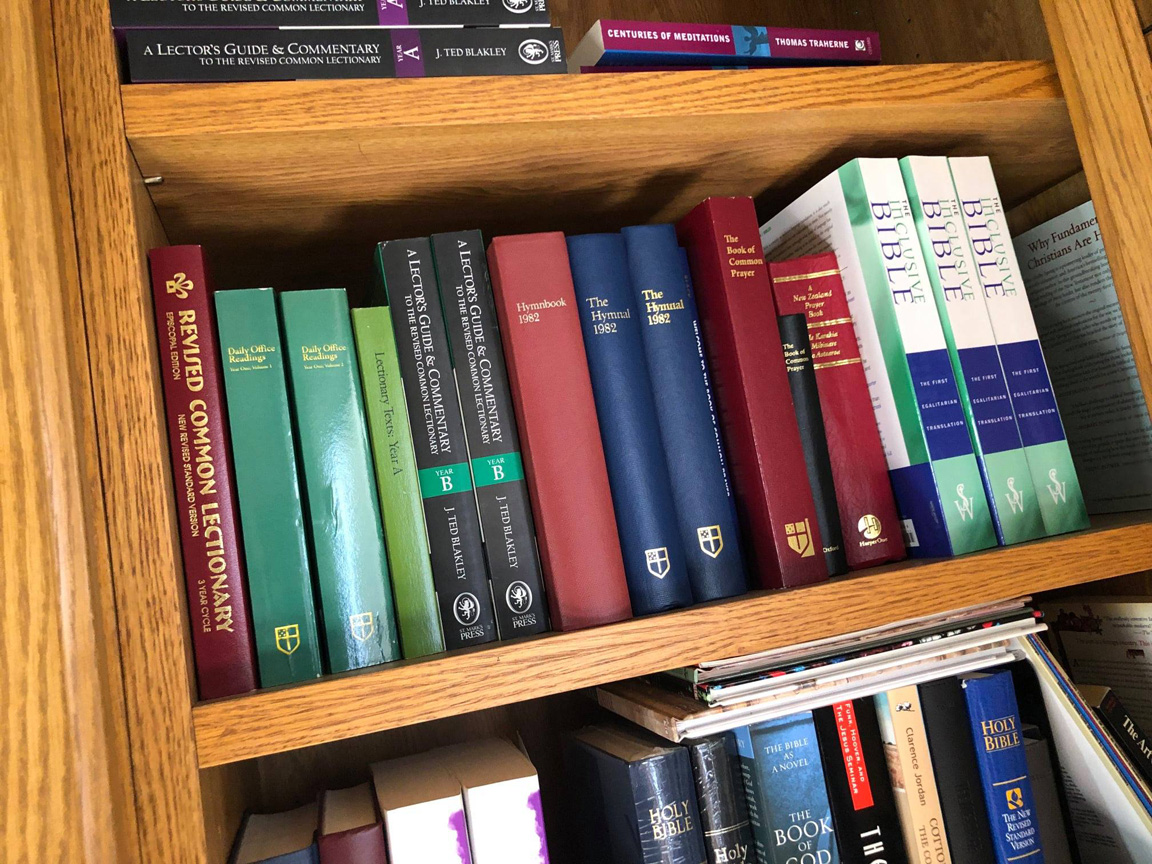

Conversation and fellowship continued over a festive lunch, including with 102-year-old former Pentagon employee, hospital and police volunteer, and scholarship founder Winnie Carter. I got a tour of the St. Luke’s bookstore, where the stock and shelving from the now-closed St. Paul’s Commons, Echo Park, bookstore experience Resurrection life, and blessed Hektor Rivas, sexton and maintenance manager these 30 years, and his family.

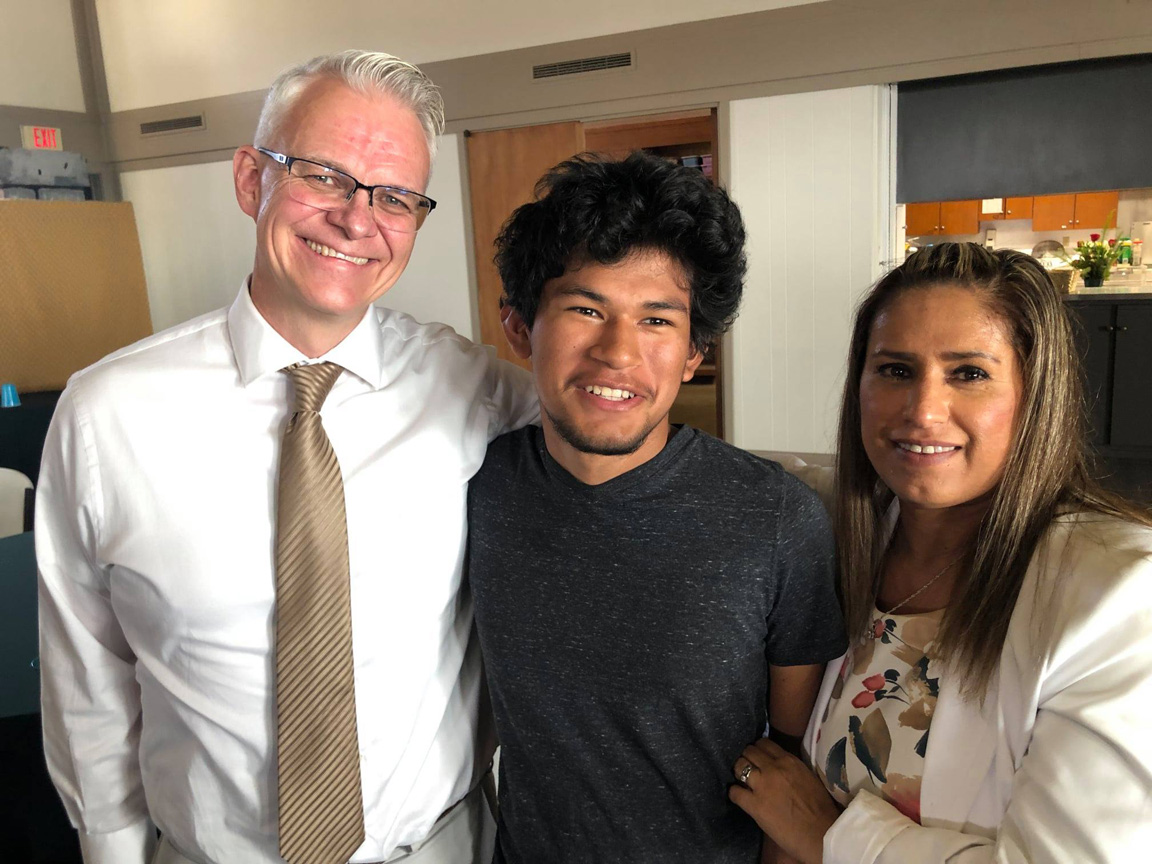

Benjamin Galan, a gifted college teacher in the midst of formation for Holy Orders, served graciously as my chaplain. His son, Salamon, a high school sophomore and violist, helped me understand how people end up playing the viola instead of the cello or violin, because I’d always wondered. In Salamon’s case, his teacher administered a test that showed he found mid-range pitches most pleasing. Typical Anglican!

I even got to compare Andover notes with Jane’s spouse, John, a former Phillips Academy English instructor. During the regular school year, he was one of two house counselors in a dorm called Rockwell, where I lived one summer, also as a counselor, when I taught journalism at the Andover Summer Session — which means, now that I think about it, that John and Jane and I have a 50-50 chance of having shared an address.

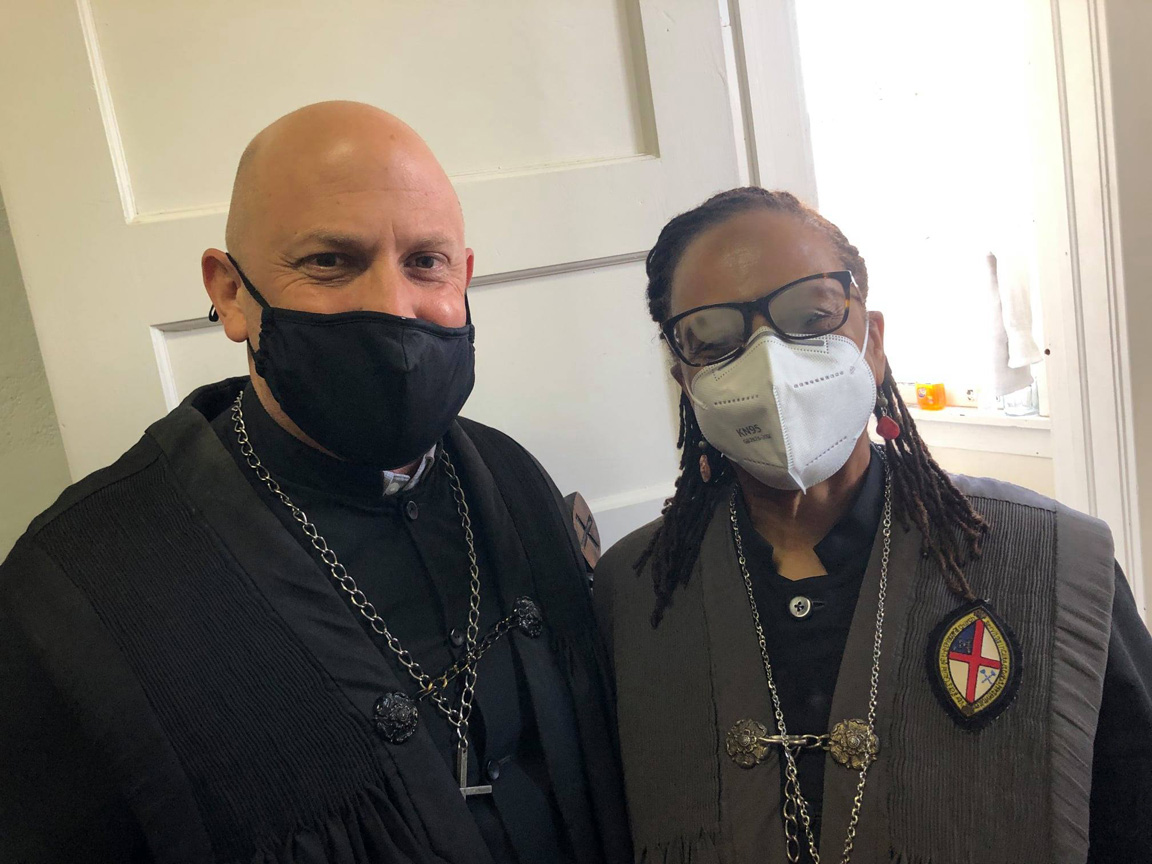

After all this and more, I told Jane that those preparing journal articles and conferences on how to build up the church we need in the 21st century should just hop a JetBlue and spend a week at St. Luke’s. Inspired and inspiring lay leaders as well as Jane’s energy, creativity, and deep understanding of the church are obvious factors. She is quick to acknowledge the legacies of the prior rector, Canon Commins, and former associate rector the Rev. Nancy Frausto, now a seminary professor in Texas. Jane works with a gifted colleague cohort, including the Revs. Dean Farrar, Dr Jennifer Hughes (a UC Riverside history professor who gave me a copy of her new book, “The Church of the Dead: The Epidemic of 1576 and the Birth of Christianity in the Americas”), Peter Huang, and Beryl Nyre-Thomas as well as the Rev. Steve Alder, parish deacon for seven years.

Read more about St. Luke’s here.