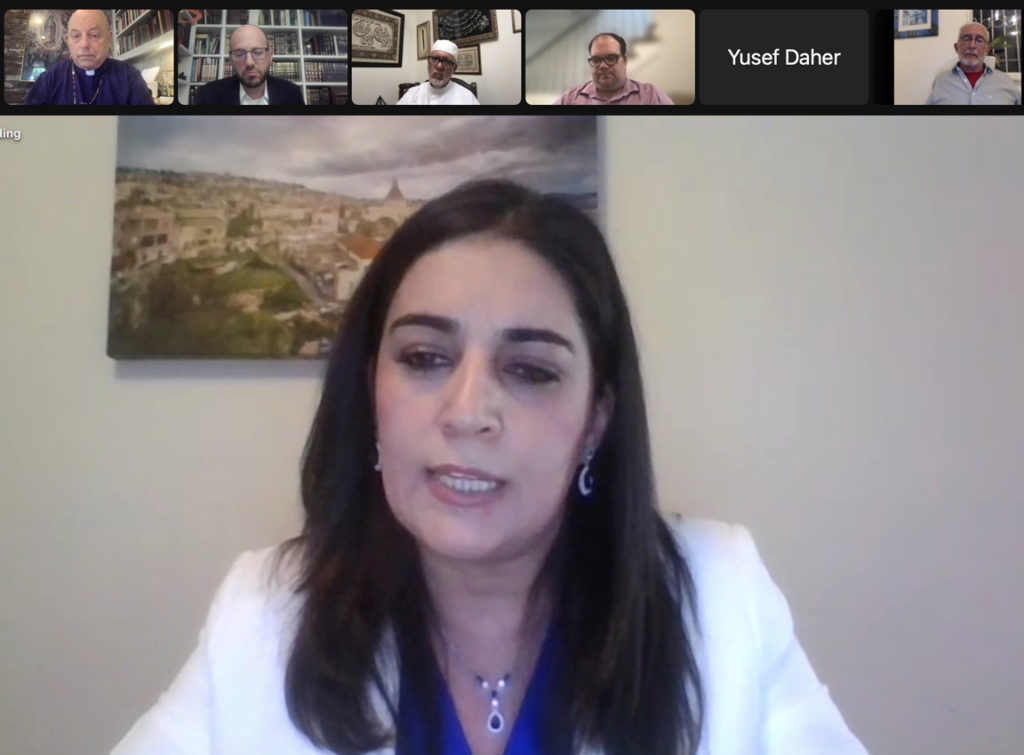

Professor Mustafa Abu Sway, Imam Al-Ghazali at Al-Aqsa Mosque and dean of the College of Islamic Studies at Al-Quds University from 2014 to 2020, was among the panelists at the Oct. 8 CMEP discussion of Middle East tensions. Photo: Screenshot

[The Episcopal News] Without international church and political advocacy, long-simmering tensions in the Middle East threaten to escalate into a global holy war, according to a panel of experts convened by Churches for Middle East Peace at the invitation of Bishop John Harvey Taylor, as the Nov. 11 – 12 diocesan convention prepares to welcome Jerusalem Archbishop Hosam Naoum as keynote speaker.

Taylor, in opening remarks at the Oct. 8 online town hall, called upon Episcopalians “to study, read, debate, follow the news,” and make pilgrimage to Israel/Palestine. He also urged advocacy and prayer for political solutions to increasingly religious conflicts over land and identity. “Never forget that members of the U.S. Senate and House read their mail,” he said.

“Find out who works on these issues in Washington and let them know what you think. Pray – and this is perhaps most important – my daily prayer is this, that all the people of the region will, by grace and by the work of peacemakers, receive what they and all of us deserve; security, peace, freedom, and the right to national self-determination.”

Kyle Cristofalo, CMEP senior director of advocacy and government relations, who served as panel moderator, said the Washington, D.C.-based organization’s goal is to shift U.S. policies “toward a hopeful end to conflicts in the Middle East, with particular attention to Israel/Palestine.” Through a network of 34 partner mainline Protestant and Orthodox Christian communions, the nonprofit organization focuses on education, advocacy, and “elevating the voices of peacebuilders on the ground.”

The five-member panel of Jerusalem- and U.S.-based experts, when asked to send a message to the international faith and political community, called upon them to visit, talk with people, witness conditions on the ground, and renew peace-building efforts.

The 90-minute town hall may be viewed here.

Rabbi Daniel Roth addresses the CMEP town hall meeting on Oct. 8. Photo: Screenshot

Seeking a just, sustainable peace

Chances for a just and sustainable peace in the Holy Land are slipping away, without the support of the international faith and political community, said Yusef Daher, coordinator of the Jerusalem Liaison Office of the World Council of Churches.

The WCC’s 11th General Assembly, meeting in Karlsruhe, Germany in September 2022, called upon “all Christians and churches of the world (to) come together and think about new prospects, and new opportunities for a better solution,” Daher said. The WCC cited a December 2021 statement by the Patriarchs and Heads of Local Churches in Jerusalem, detailing increased attacks on priests and property “by fringe radical groups … in a systematic attempt to drive the Christian community out of Jerusalem and other parts of the Holy Land”.

Radical groups – right-wing extremists across the political spectrum – and government policies have heightened ongoing tensions, particularly between Israelis and Palestinians living in East Jerusalem, said panelists.

Tensions have continued to rise around the Al Aqsa Mosque, sacred to Muslims as the place where the prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven, and known to Jews as the Temple Mount, the place where God was revealed on earth. Violence broke out at the mosque on May 21, 2021, a few hours after a ceasefire was declared in an 11-day conflict between Israel and Gaza’s Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

Professor Mustafa Abu Sway, Imam Al-Ghazali at Al-Aqsa Mosque and dean of the College of Islamic Studies at Al-Quds University from 2014 to 2020, said authorities on Oct. 8, 2022 detained and fined Muslim worshippers praying at the mosque – where Palestinian youth and police frequently clash. “The police have no right to detain people for praying anywhere, and they should not define the mosque for us.”

Rabbi Daniel Roth, director of the Religious Peace Initiative with Mosaica, which works to advance religious peace and mitigate crisis situations, said peacebuilding currently feels like being “stuck in the mud.” He fears a reprise of violence seen on May 21.

“We’re at a very important crossroads; a lot of our work right now is, how do we engage the most influential and often extreme religious leaders around the Middle East, in particular Islamic leaders, the Muslim Brotherhood and others, and the most extreme, influential religious Zionist settler leaders, that are pushing us closer to what might be a holy war,” he said.

Mediation – not ecumenical dialogue – is needed, to “engage each from their place and speak within their language, so that we can alter the course of what we’re heading towards,” and advocate for a “warm, religious peace, that changes the way people are seeing their prophetic visions, in a way that is meaningful.”

Suha Salman Mousa, co-director of the Mossawa Center, the Advocacy Center for Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel, responds to an issue during the panel discussion. Photo: Screenshot

Ongoing political and discriminatory legal systems further complicate challenges on the ground, said Suha Salman Mousa, co-director of the Mossawa Center, the Advocacy Center for Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel, which promotes Palestinian Arab rights in a democratic society.

For example, Palestinians living in East Jerusalem are not Israeli citizens but hold only permanent residency, which can be revoked, along with their right to live there again if they move away. Mousa’s eldest son is among thousands of Palestinians whose official status has been revoked, she said. “He was born in Jerusalem. He lived in Jerusalem. He’s part of Jerusalem; Jerusalem is part of him. Why should this be? Why should the law be there in the first place?”

Similarly, the 2018 “Nation-State Law … essentially defines Israel as a state with the right of national self-determination, being an exclusive right only for the Jewish people,” she said. “In order to protect the holy city and the holy sites for all religions, to protect freedom of worship, we must protect the people living there,” she declared. “We must protect the human and the civil rights of the Palestinians who are denied their most basic rights every day.”

Daniel Seidemann, who has lived in Jerusalem since 1973, has been a member of the Israeli Bar Association since 1987, and specializes in commercial law and land projects, said the religious extremism, coupled with Israeli government urban planning, potentially could endanger the future Christian and Muslim religious presence in Jerusalem’s Old City.

“The impact, first and foremost, is upon the Palestinians … but it’s devastating for the Christian presence in the city,” he said. “This goes far beyond the occasional abuse of clerics on Mount Zion.”

Citing the vulnerability of the Christian community – which since 1922 has declined from 25% of Jerusalem’s population to less than 1% – Seidemann said erection of a pedestrian mall at the entrance of the Christian Quarter in the Old City, and plans to impose a national park over Christian sacred sites, demonstrate the government’s intention to further fragment Palestinians in East Jerusalem, socially, economically and politically, and to encourage “the marginalization of Christian and Muslim identities in Jerusalem.”

The national park plan was shelved after churches protested.

Like other panelists, Seidemann called upon international faith communities to visit the Holy Land, talk to its people, support peacebuilding organizations and advocate with the U.S. Congress for change.

“This will not go away on its own, and it will not go away by expressing opinions,” Seidemann said. “It will go away by a concerted effort by those faith communities who will recover the high ground, … and empower the secular leadership to engage Israel on this rather forcefully. That is an achievable goal. There is room not only to engage Israel in stopping these developments, but by creating the faith-based alternative, to restore the credibility of a multi-phased Jerusalem where no community needs to struggle.”

Roth agreed that religious advocacy is essential, especially with the Nov. 1 victory of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his right-wing party, and the failure of the Arab nationalist party Balad and Ayelet Shaked’s Habayit Hayehudi to garner enough votes to make it into the Knesset, Israel’s governing body. It means “the Islamist party will not be able to be part of a coalition to advocate for Palestinian Israeli rights, as well as the Palestinian cause … (giving) the right-wing Israeli government a full coalition.”

Right-wing Israelis don’t “trust the Americans, certainly not the Biden Administration,” Roth added. “It’s religious leaders that can hopefully try to come here and engage with the right-wing Jews, and … try to help us think differently from a trusted place out of this situation.”

He recalled efforts of former Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury George D. Carey, who in 2002 helped broker a religious peace agreement in Alexandria, Egypt, “during the height of the Second Intifada, when all the politicians and military forces were in a deadlock. But religious leaders were able to come together and say, can we find a way out of this in this increasingly religious conflict, and it was the Anglican Church that helped play that role as a mediator.”