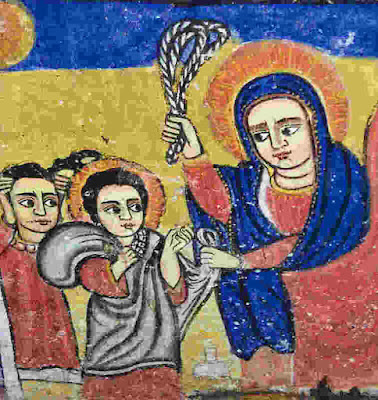

Mary punishes Jesus, from a 14th century mural found in Ethiopia

In a song called “Mary Mild” on “The Last Month Of The Year,” the Kingston Trio’s 1960 Christmas album, three boys of noble birth won’t play with Jesus because he was “but a poor maid’s child, born in an oxen stall.” So he builds them a bridge from the beams of the sun over pools of water in the neighborhood. Exactly where this type of activity would have occurred in first-century Palestine, the song does not say. When the boys drown while playing on their stairway to heaven, their mothers beg Mary to call Jesus home.

The song is based on an English ballad, “The Bitter Withy,” dating from the late 18th century, which tells of Mary punishing Jesus by beating him with a willow branch. This and other stories of young Jesus misusing his superpowers come from the second- and third-century apocryphal literature, early Christianity’s means of filling in the blanks, or accounting for apparent discrepancies or inconsistencies, in the biblical canon.

It’s of course horrifying to think of our Lord causing these children’s deaths. Hunting for the lyrics, I found a version saying not that anyone died but that the mothers’ “eyes [were] all drowned in tears.” Would that this were the case. On the record, the Trio has their mothers saying of their children, “For they all drowned be.” In “Mary Mild,” Jesus’s action seems innocent. But in the 18th century song, he builds the bridge for himself, and the lords’ and ladies’ sons drown when they try to follow him.

The nobles don’t dare send assassins for Jesus and Mary, as nobles normally would. To the balladeers, he was not the prince of peace but a little god of vengeance. Jesus the class warrior. One could easily imagine people oppressed enough to worship such a savior. Don’t forget the bit we usually leave out when reading from Psalm 137, which records the lament of those taken into exile by the Babylonians: “Happy shall they be who take your little ones and dash them against the rock!”

By and large, this is the corner where we’ve kept Jesus. He’s our two-fisted champion. Crusaders sacked Jerusalem and massacred Muslims in Jesus’ name. Preachers waved the Bible while sanctioning slavery and colonizing half the world. Sometimes it’s understandable to think God’s on our side. The allies prayed Jesus would lead them to victory in World War II. Especially this bleak midwinter, Ukrainians are entitled to pray for his protection and for victory over the tyrant. I sometimes have joined them.

Yet by 1865, as the Civil War came to an end, Abraham Lincoln, a pretty good theologian, understood that it was getting hard to go onward with the idea of Christian soldiers. “Both [north and south] read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other,” he said in his second Inaugural address. “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.”

Yet we have a tendency to put Christ to work for our purposes. Maybe I want a guardian to protect my privilege, a moral arbiter to keep my church pure, or a national savior. It’s the human thing to do. I don’t know what fate I would pray for Putin if I were in a basement in Kyiv without heat or electricity, cradling a sick child. Vengeful feelings like those in Psalm 137:9 would no doubt bubble to the surface. Same if I were the parent of a trans child being scapegoated by state legislatures, or of one of the cops Trump’s mob attacked on Jan. 6. But if the baby came down for me and those I love, he came down for everybody, even the Christians who sacked the Capitol and scapegoat trans children. Even Putin. The prince of peace is angling for a room in every heart, thus to activate our infinite capacity for peace.

In the same speech, Lincoln raised the idea of God willing the war to continue “until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.” But Lincoln couldn’t really have believed it. He hated the war; so God must have hated it absolutely. Call that the ontological proof of God’s preference for peace. God grieves every death, on all sides. Every wound. In our lives, every harsh word and action. Every injustice or act of unkindness. Every time someone has to sleep outside or go without a meal. Every time someone is left out or overlooked. Listen to “Mary Mild” if you can find it, and see how you wince at the idea of wild Jesus letting those children die. He wouldn’t. He couldn’t. And he would have us be the same. All the time, until kingdom come.