Clergy of the Diocese of Los Angeles gather for a photo during their annual conference at the Mission Inn in Riverside. Photos: Janet Kawamoto

Bishop John Harvey Taylor welcomes the clergy to the conference, which began on May 6.

[The Episcopal News] The paradox of church leadership today is that “we are Easter people in a world stuck on Good Friday,” Bishop John Harvey Taylor said during opening remarks at the May 6 – 8 annual diocesan clergy conference at Riverside’s historic Mission Inn.

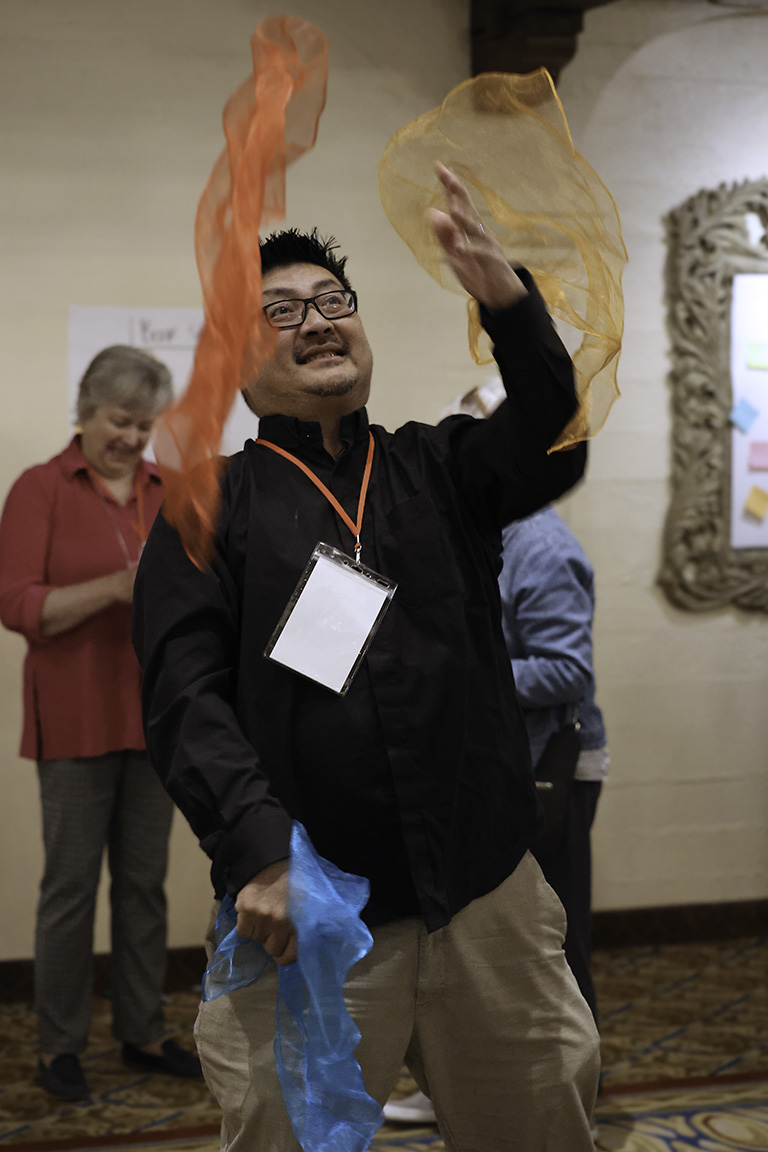

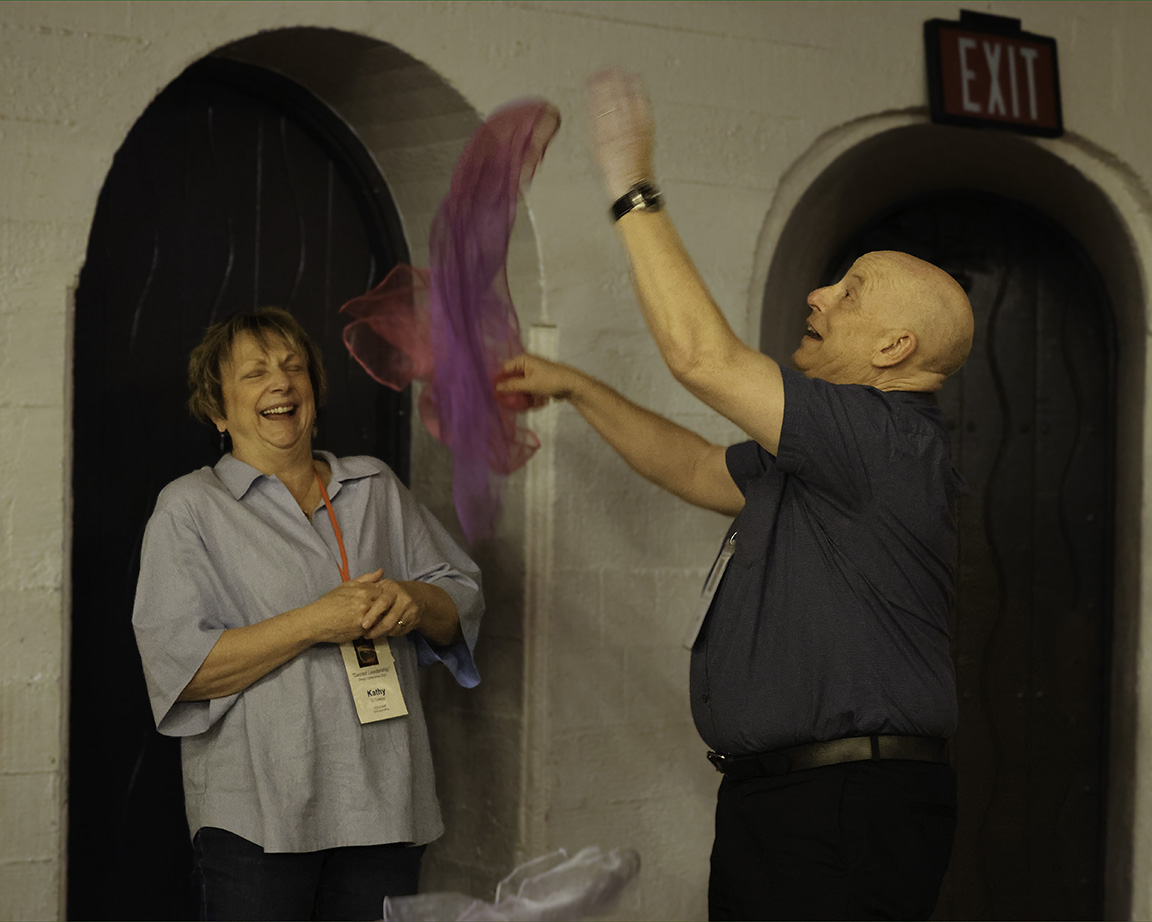

He welcomed Kathy Wilder, executive director of Camp Stevens, a ministry of the diocese, who led the conference, themed “Sacred Leadership.” Wilder, who recently completed her doctorate researching small nonprofit employee resilience, brought a camp spirit, inviting clergy to step apart from the intensity of parish ministry to experience “some time to play, to have fun, to be together, to get to know each other. That’s what Camp Stevens is all about.”

Kathy Wilder, executive director of Camp Stevens, starts Clergy Conference by teaching gathered priests, deacons and bishops to juggle scarves.

Taylor also preached at a May 8 Eucharist, affirming that “love is the only thing that works, the only thing that builds up communities, the only thing that keeps communities together.” (Read his sermon here.)

The annual three-day conference included conversations about trust management, resilience through routine and ritual, and open communication. Conference activities included worship, a screening of the Philadelphia Eleven documentary film chronicling experiences of the first women ordained priests in The Episcopal Church, and separate gatherings for bi-vocational and retired clergy.

Alfredo Feregrino, associate priest at All Saints, Pasadena, tries his hand at scarf-juggling.

“Leadership is a sacred responsibility. It’s especially sacred for you and the work you are doing,” said Wilder. She hoped to offer tools to aid clergy to create spaces for trust, transparency, connections, communication and even coaching, and “storming” or dealing with challenging conversations – all of which lead to congregational resiliency and relies upon having an established and communicated covenant or code of conduct that includes “agreements with people about your time and space, about how we interact. Transparency is a huge part of trust.”

Lenten suppers, special events and programs and potluck meals are opportunities for church members to make connections and to build trust among each other, Wilder said. “It is not our job to make people trust us. It is our job to create spaces for trust to grow.”

Similarly, resiliency involves responding to and adapting to minor change, “because it’s not just about surviving something. It’s about learning from it and thriving.” Wilder encouraged creating regular routines to enhance resiliency before challenges occur, including building spiritual practices and regular “routines around having hard conversations.”

Incorporating an invitation to difficult conversations into regular meeting agendas, for example, can promote openness, and prevent a “you versus me” environment, and ensure that everyone’s voice is heard. It is also important to communicate that sense of openness and inclusion of all voices to the congregation, she said.

Roberto Limatú of St. Anselm’s, Garden Grove and Immanuel, El Monte; Roberto Martinez of La Magdalena, Glendale; and Carlos Rubalcava of St. Luke’s, La Crescenta, pause for a photo.

Coaching and storming

Coaching church volunteers and inviting – rather than squelching – pushback against organizational norms or boundaries can also promote resilience, Wilder said. “Storms – they’re going to happen, and it’s okay. A lot of people spend a lot of time trying to squash the storm, but that storm is still happening … and there’s nothing more damaging to a community than a subversive storm,” Wilder said.

“It’s about creating a culture, a culture in your church, a space in your church, that is open to all ways of being right, that is open to all opinions, open to perspectives that you will not see. That’s very important.”

Wilder also invited clergy to consider creating spaces where accountability, but not perfectionism, is welcomed.

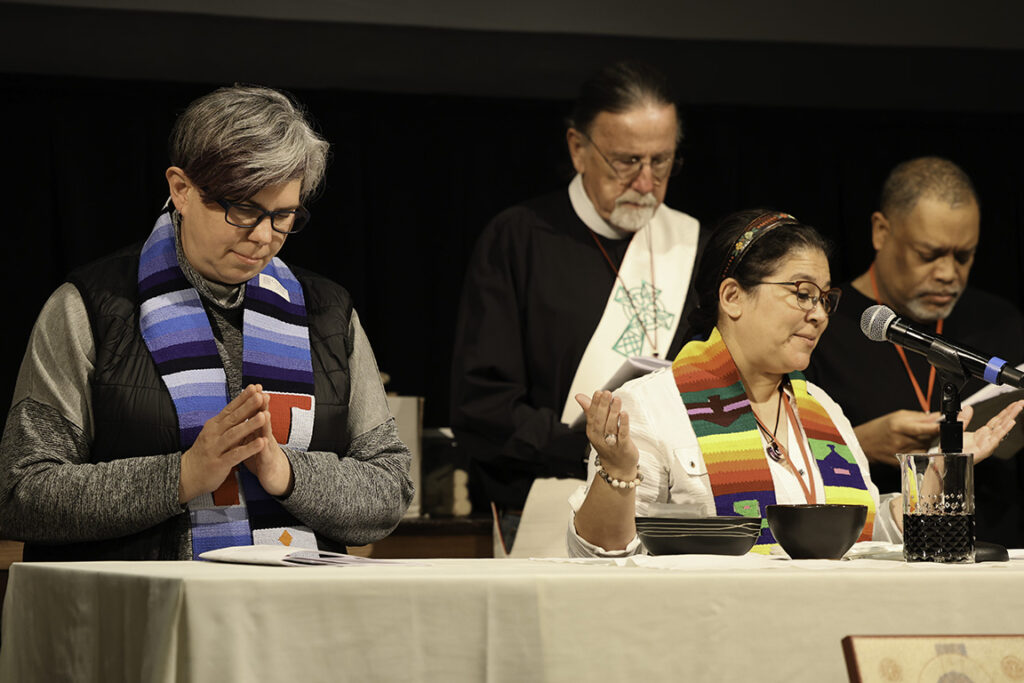

Canon to the Ordinary Melissa McCarthy and Associate for Formation & Transition Ministry Norma Guerra celebrate Eucharist to close the conference.

“We are culturally taught to be perfect. And I cannot reiterate enough about how important it is to create space where this is not something you’re expecting, … although we want people to be accountable. We want people to show up for the work they’re doing, for the way that they’re being in the community. But perfectionism is an unreal standard.”

Taylor said the Rev. Carter Heyward, one of the Philadelphia Eleven featured in the documentary film shown at the conference, will serve as keynote speaker at the upcoming Nov. 8-9, 2024, diocesan convention at the Riverside Convention center.

In the film, “Dr. Heyward said there are some people who just happen to be called to explain and show by virtue of their very being that God is all about justice, compassion, kindness, and mercy, modeling the incarnationality of God, the love of God and healthy networks of human relationship,” Taylor said during the concluding Eucharist.

Bishop Taylor blesses the clergy to conclude the Eucharist and the conference.

“But in our society, bulwarks are replacing networks. We’re more and more isolated from one another by race, age, region, degrees of educational attainment. social economics. It’s not even that we don’t love our neighbor. It’s even worse than that. We don’t notice our neighbor more and more.”

But “curiosity always leads to understanding, which leads to empathy, which leads to love, which leads to obligation.”

Curiosity about our neighbor “is a gospel imperative,” Taylor added. “We are required to speak up and stand against any ideology, creed, doctrine, platform, or policy, including all the principles governing law enforcement, our justice and penal systems, our immigration and asylum systems and the way we use power in the world and what we do with our money.”

Clergy practicing scarf-juggling include, from top: Israel Anchean, vicar of Christ the King, Santa Barbara and Michael Bell, director of housing and business development for Episcopal Communities & Services; Mary Tororeiy, vicar of St. Paul’s and Shepherd of the Desert, Barstow; Neil Tadken, rector of St. Luke’s, Monrovia; Susan Scranton, rector of Grace Church, Glendora; Mel Soriano, associate priest at All Saints, Pasadena; and Bishop John Harvey Taylor, with his spouse, Canon Kathy O’Connor.