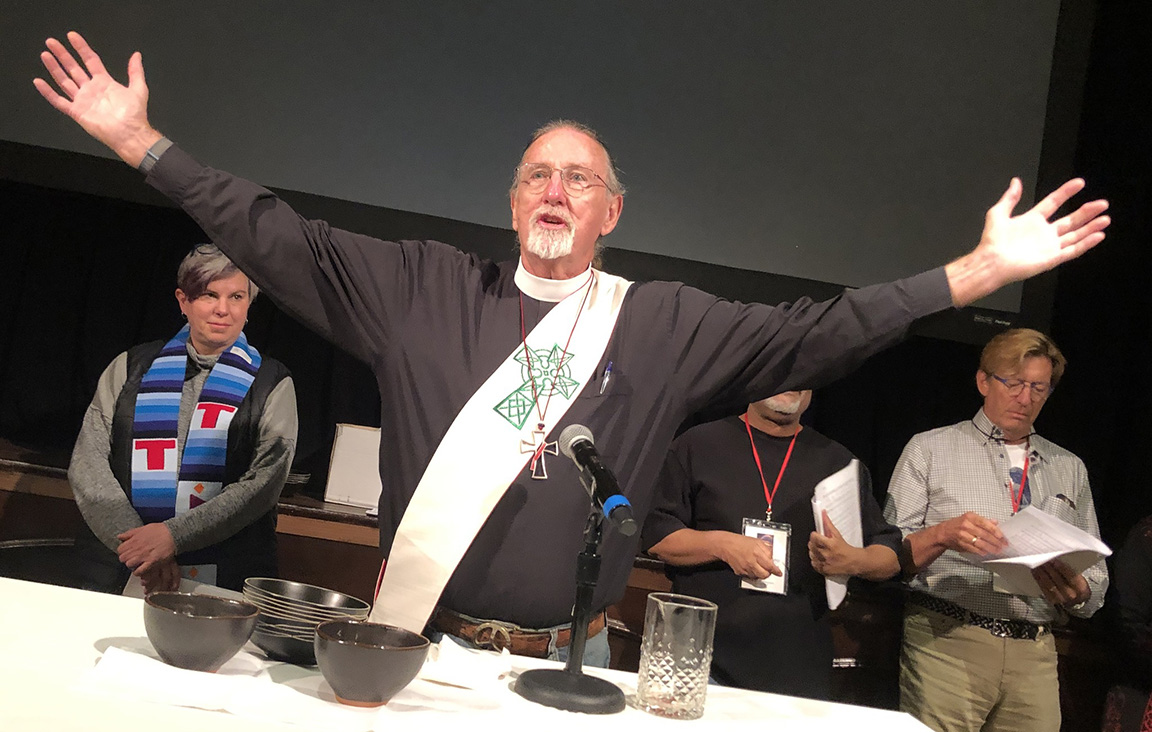

At the conclusion of Clergy Conference the Rev. John G. Draper, who serves weekly in the Federal Correction Institution in Lompoc, sends us out into the world rejoining in the Holy Spirit as the Rev. Canon Melissa McCarthy, who celebrated Holy Eucharist, looks on. Photo: John Taylor

You may remember it from our conversation yesterday, when Dr. Kathy Wilder was helping us with conflict management. Jamie, vicar of The Church of the Epiphany in Oak Park, stood up and talked about the holy space that exists between stimulus and response.

We absorb that thoughtless comment, that shaming email, that belittling criticism. We’re tempted to respond in kind, but our training and experience make us wait. In that holy space, we find the means of grace. The authority of forgiveness. Finally, our feet find their way back to Presiding Bishop Michael B. Curry’s sacred way of love. The grace of reconciliation smothering the spark of escalation.

It takes time – sometimes a lifetime — but we eventually learn that love is the only thing that works, the only thing that builds up community and keeps community together. Sometimes the essence of our diaconal, episcopal, and sacerdotal ministry is in the silence and the waiting — in the intentional doing of absolutely nothing — until we’re prepared to speak and act in love.

In our first reading this morning, you probably noticed the reference to another holy interval of time. In May of 1373, after a childhood and young adulthood buffeted by trauma – political and religious conflicts in her native Norwich, not to mention the Black Death – in 1373, when Julian was thirty and fell gravely ill, she experienced a series of ecstatic visions of Jesus.

Our traditional understanding is that she wrote it all down right away. But as we heard today, it was 15 years before she fully discerned its meaning. She said it took further visitations from our risen Lord. It took 15 years before she was prepared to interpret her “shewings” as proof that love was the alpha and omega.

Julian’s signature assurances are that all manner of things will be well, that we are only to love more and more, that love is the beginning, the end, and the middle. These words roll easily off our lips in these Julian day sermons, but they took their author a generation to utter. We would have to know more about Julian’s life to know why it took her so long.

And so it always goes. If love were easy, everyone would do it all the time. If love were more profitable, no oppressor would have their day. Love does come naturally, only to be smothered by our unnaturalness. If love were the first choice of people in power, no child would suffer, no one would sleep on the street, no one would miss a meal, no one would dine alone. No bomb would fall. No one would weep in the rubble.

But the world operates according to other doctrines. Running pointlessly for president in 2015, talking about immigration, Jeb Bush said that many of those entering our country without documentation to find work and a better life were doing so out of love for their families – which was absolutely correct. And then Trump wrote a TV ad that said: “Love? Forget love. It’s time to get tough.”

“Forget love.” That’s one way to make America great. “Forget love” set the tone for our debased discourse these nine years.

In fairness to Trump, love for love’s sake is rarely proclaimed in politics. Coming first, because sometimes they have to, are struggles against privilege or to keep privilege. Making peace or profiting from war. Harvesting justice or leaving it to die on the vine. Balancing interests and making deals.

Love, it is said, is just for our families or tribes, or something we talk about when we worship Friday at noon, Saturday at sunset, or Sunday morning at ten. Yet thinking even of our fellow people of faith — the extremist Israeli West Bank settler and the Hamas fighter — their scriptures, like all holy scriptures, proclaim the primacy of love. But grievance or suffering curdles the milk of kindness, and people look among sacred texts and find warrant for genocide.

Over and over again in human affairs, something comes before love. Yes, if love were easy, we’d do it all the time.

If you’ve seen the documentary on the Philadelphia 11 that Susan showed yesterday afternoon, you may remember what the Rev. Dr. Carter Heyward says about priesthood. She’ll be with us for convention in November, and it’s really going to be fun. Dr. Heyward said there are some people who are called to explain and show that God is always about justice, compassion, kindness, and mercy – modeling the incarnationality of God, the self-giving love of God, in healthy networks of human relationship.

But in our society, bulwarks are replacing networks. We are more and more isolated from one another by race, age, region, degree of educational attainment, and socioeconomics. “Forget love” is a slogan that can only take hold in a culture where curiosity is on its last legs. It’s not even that we don’t love our neighbor. It’s even worse than that. We by and large don’t notice our neighbor.

But on Tuesday morning, after we interviewed one another, Kelli Grace mentioned “my new friend Shane.” Curiosity built a bridge from Riverside to Corona del Mar. One ordained by Bob Anderson in Los Angeles, the other by Benedict XVI in Rome. Kelli Grace and Shane didn’t need the exercise. They’re priests according to the order of Carter Heyward, and they would have discovered one another in good time.

But even we overperforming practitioners are prone to incuriosity. We too can fall victim our digitalized, polarized economics and politics, their shrewd brokers using lies and algorithms to maximize their profit and build up their power.

Because here’s our secret – and the power brokers know and fears this. The secret is that curiosity always leads to understanding, which leads to empathy, which leads to love, which leads to obligation. Curiosity, understanding, empathy, love, obligation – think of the Spanish work “cuelo,” which means neck, connecting the loving heart with the calculating head.

Shortening the equation, curiosity can beget obligation. We all get this. We all know that asking a stranger at Starbucks how they’re doing may entail a deeper incarnational connection with a fellow child of God than we may be willing to entertain when we’re on the way to work or the way home. And saints preserve us from the parishioner with the same old story or beef every Sunday at coffee hour.

Acting in love almost always ends up being inconvenient. It can use up our resources. And it can be dangerous. Another of the pioneering 15 women priests, Alison Mary Cheek, described in the documentary what it felt like when she learned of plans for their ordination service in July 1974. She said her heart leapt up, but then the news made it up from heart to neck to her wise head, which began pondering the consequences.

Because it’s never easy or safe to proclaim the primacy of love and mutual obligation. Ask the Philadelphia 11. Ask Mandella. Ask Dr. King. Ask advocates for the trans woman in Georgia who just wants to play on her college volleyball team.

My beloved colleagues, it’s hard to do what we do these days. It’s hard to lead well in unwell times. Leave aside the existential dread of this particular political year. The truths we hold to be self-evident, beginning with love your neighbor as yourself and the idea that curiosity about our neighbor is a gospel imperative, since our neighbor is made in the image of God — these ideas are losing their hold on the public’s imagination.

But I don’t think we can have a decent society without them.

I don’t think the United States will endure without a communitarian ethic rooted in the recognition that every person has a degree of moral obligation to every other person.

So we can give up and go home. The last one out can snuff out the sanctuary candle.

Or we can stay and hold the line for our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.

In the 21st century, secularism is in the ascendant, and sacred leadership must make its peace with it. People just aren’t as interested as they used to be in our doctrines and denominations.

But this will never absolve us of our responsibilities as people of faith – people who by grace know that all creation is made in love, saved in love, and bathed in love.

We are entitled and required to speak up and stand against any ideology, doctrine, platform, or policy, including the principles governing law enforcement, our justice and penal systems, our immigration and asylum system, and the way we use power and our money in the world – the gospel requires us to stand up and say no if the proponents of any ideology or policy can’t identify its antecedents in the alpha and the omega, Jesus and Julian’s universal law of love.

Borrowing one of the concepts in Dr. Wilder’s closing presentation this morning, this goes in the box marked “urgent AND essential.” When it comes to the primacy of love, there can be no separation of church and state.

— My sermon at the closing Holy Eucharist service Wednesday morning at our annual Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles clergy conference in Riverside. Our conference speaker was Dr. Kathy Wilder, executive director of Camp Stevens.