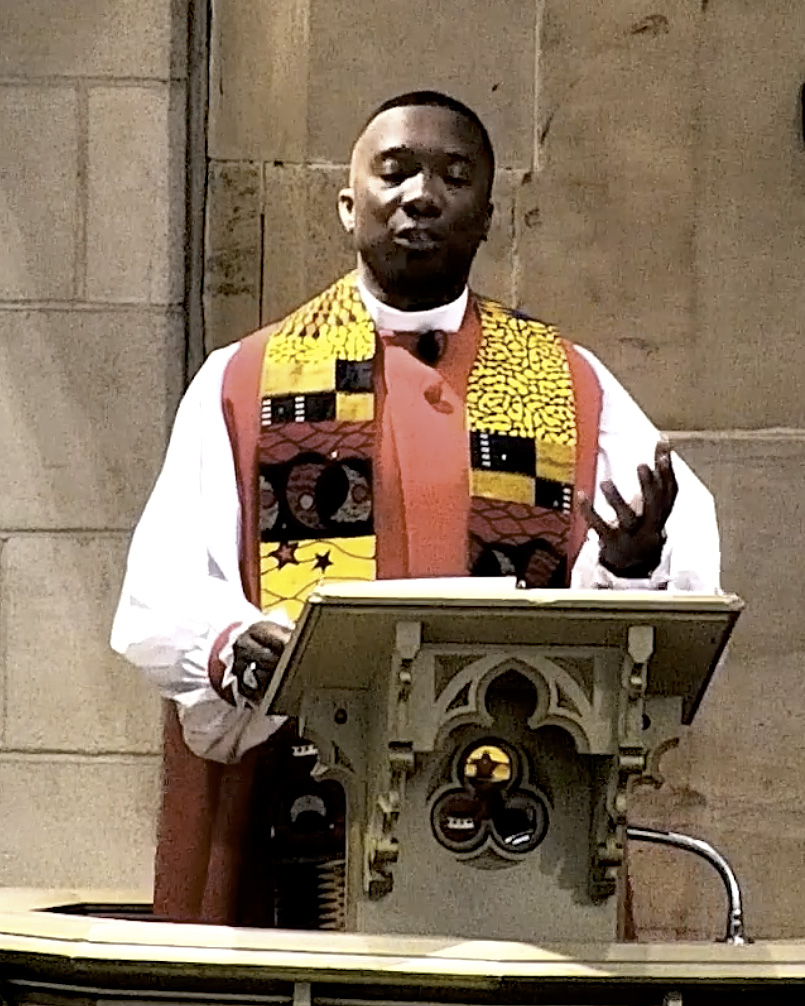

Bishop Deon Johnson of Missouri preaches at the Diocese of Los Angeles’ online Martin Luther King Jr. commemoration Jan. 15. Photo: Screenshot

[The Episcopal News] The Jan. 15, 2022, diocesan celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., “Common Struggle, Common Hope,” featured calls to action from The Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry and guest preacher Missouri Bishop Deon Johnson, spirited music, and reflections from Asian Pacific Islander, Latinx, African American, Native American and LGBTQ members of diocesan New Community ministries.

Hosted in person by Christ the Good Shepherd Church and livestreamed via Facebook and You Tube, the service began with videotaped greetings from diocesan Program Group on Black Ministries co-chairs Canon Susan Edwards Acton and the Rev. John Limo and acknowledgement that the land on which the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles is located belonged to the Tongva people.

“Eighteen treaties were made between 1851 and 1852 with the California tribes, that the U.S. Senate decided not to ratify in secret session at the request of the state of California,” according to Roselyn Smith, of the Pima Saltwater Maricopa Indian Communities. “If the treaties had been honored, the tribes would possess more than 7.5 million acres of land in the state. But today, California tribes own about 7% of the unratified treaty territory.”

Calls to action

Curry, in a Jan. 6 videotaped message from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the one-year anniversary of the capitol riots, cited “forces intentionally seeking and working to divide us. Left unchecked, unaddressed and unhealed, this can lead to the decline and deconstruction of our nation.”

The promise of the United States “as the multiracial, multiethnic, pluralistic democracy that was envisioned … becomes a real and greater possibility if enough of us will summon the spiritual courage necessary to attain it,” Curry said. “It is not an exaggeration to say that we are living in a moral moment of spiritual peril and promise. Such a moment demands moral vision that sees beyond mere self-interest and beholds the common good – a spiritual strength, stronger than any sword.”

Diocesan Bishop John Harvey Taylor served as officiant, recalling King as “both prophet and pastor.” Former Los Angeles Suffragan Bishop Diane M. Jardine Bruce introduced Johnson via a prerecorded message.

Johnson, preaching from Christ Church Cathedral in downtown St. Louis, noted that although King went up the mountaintop and saw a transformed world, he returned and championed the cause of sanitation workers and bus drivers, the poor and unhoused, adding: “God has work for us to do.”

“It is time for you and I … to come down from the mountains of our beautiful buildings and our solemn liturgies and go into the valleys of despair and set all of God’s people free,” Johnson said. “If what we do on Sunday makes no difference on Monday, we have neglected the dream. If we are more content with reading a book on race than going out and doing the hard work of building relationships, we have neglected the dream.”

Casting a new vision, he added: “We must go and tell the dream, go out and dare to be the dreamers, go out and live the dream of a world transformed. We must not just dream. We must dare, and then we must do.”

New Community reflections: creating beloved community

King’s ministry encompassed all people as beloved community, members of diocesan New Community ministries said.

Dustin Nguyen, from The Gathering, a space for Asian Pacific Island American Spiritualty, a ministry of the diocese, connected King’s image of “an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny” with the African concept of ubuntu; “I am because we are.”

“In Vietnam we have our own version of ubuntu,” he said in a pre-recorded message. “We have the saying, lá lành đùm lá rách, which translates to ‘the whole leaf envelops the torn leaf.’ Vietnamese rice cakes are wrapped in layers of leaves and so the whole leaves on the outside … help reinforce any torn leaves underneath. Symbolically, this represents solidarity, interconnectedness. I am because we are. This is the way we create beloved community, because none of us are free till we’re all free.”

Leaving her El Salvador home in 1980 and seeking a better life in the United States was a tough but necessary choice for Sandra Martinez-Moore, but her dreams of golden opportunities faded, she said.

Those dreams “can be true for many, but for a Latina woman with dark hair and skin, this has not been 100% free, nor 100% full of opportunities. My struggle continues day to day. That struggle is much easier now than when Dr. King was alive. I have his dream, the dream that someday the nation will treat me and everyone equal. My dream, I am hoping that one day I will be 100% fearless, if I get pulled over by a police officer, or to know that my dark-skinned son is not at risk of being profiled, searched, and handcuffed, just because his skin is dark.

She has gained courage “to stand up and to stand tall, to feel that I’m valued, that I am worthy, that I am somebody, but that has not come easy,” she added. “There have been many struggles to get opportunities, many sacrifices, and it’s not over yet. But the dream continues.”

Casey Jones, vice president of the H. Belfield Hannibal chapter of the Union of Black Episcopalians, recalled experiences growing up in Columbus, Georgia, about an hour from Montgomery, Alabama, and as an undergraduate student at King’s alma mater, the historically Black Morehouse College in Atlanta, “where everybody has a story about Dr. King.”

Jones told one particularly powerful story: “[A]s a child … Dr. King was convinced he could fly. They say that he jumped from the second story of his house, to prove, I guess, to himself and to the rest of the family that he could fly. As I think about the legacy of the life of Dr. King to our community, it strikes me that he was the guy who was convinced he could fly. And he’s the guy who convinced us that we could fly. He convinced this nation and this world that, with love, with compassion for one another, that we could soar to the heights and the depths of our humanity and become one beloved community.”

Kathleen Dvorak Ashelford, of the Cheyenne River Lakota Tribe and a member of First Women Around the Fire, a diocesan ministry, said that, although King’s contributions to Native American rights “are enormous,” they are not widely known.

She cited King’s 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait, in which he wrote, “Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shores, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. We tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out our indigenous population.”

“Dr. King advocated specifically for the desegregation of Native Americans in school systems,” Ashelford said. King met with tribal leaders, and his work inspired the founding of the Native American Rights Fund, the “oldest and largest legal advocacy group” for Native Americans, she said.

“While King’s courage and dedication cost him his life at an early age, his teachings live on in all those who seek justice. King’s dream was for all God’s children.”

Thomas Diaz, a parishioner at All Saints Church in Pasadena and a L.A. deputy to The Episcopal Church’s 2022 General Convention, cited the witness of Bayard Rustin, a key but relatively behind-the-scenes King advisor for the 1963 March on Washington.

Rustin’s gay identity cost him that visibility, but he maintained that his identity as an African American went hand in hand with his identity as a gay man, Diaz said. In an interview with The Village Voice, recovered in 2019 by National Public Radio, Rustin had said, “It was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality, because if I didn’t, I was a part of the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me.”

Diaz said: “As King proclaimed, freedom is not won by the passive acceptance of suffering. Freedom is won by the struggle against suffering. People like myself, and my gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender siblings know a little bit about passive acceptance. We also know its sufferings and yet we have also made great strides to overcome it.

“We have so much more work to do, to bring along the full liberation for all of God’s children in this country,” he said. “But take heart, because our struggle is the gateway to freedom. We as gay, lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender children of God … are the leaders to this freedom.”

King stood with civil rights leaders to make this freedom possible, he said. “May we be reminded on this day of remembrance of Dr. King that … our struggle will continue to turn into liberation for all peoples. So, keep proclaiming this liberation and its truth. Keep the faith. The Spirit is alive in us. Let us continue the holy work of liberation.”

A history of Christ the Good Shepherd Church

Leonard Jolly-Blanks shared the history of Christ the Good Shepherd Church, born of the merger of three local Episcopal congregations in Los Angeles: St. Andrew’s (founded 1906), Good Shepherd (1912), and Christ Chapel, a mission of St. James’ Church, founded in 1953, and renamed in 1957.

A new church was built at Eleventh Avenue and Vernon and the first service was held in 1959. Jolly-Blanks cited the church’s long history of community outreach and support, including the 1975 establishment of Good Shepherd Manor, affordable housing for senior citizens. In 1986 the church was named a Jubilee center and later sponsored a Black college tour, enabling young people to expand their higher educational opportunities.

Through the church, Canon Percia Hutcherson, a physical therapist and longtime medical missionary, established Mission Kenya, a collaborative outreach between the congregation and the Diocese of Eldoret in East Africa, to assist persons with disabilities. She was also instrumental, along with the church and the Los Angeles diocese, in establishing Good Shepherd Homes, an apartment complex for persons with disabilities.

The church has continued to be a vital presence, providing meeting space and community outreach, including food, clothing and other items monthly, he said. The congregation “continues to serve others and follow the example of Christ in caring for the community.”