Lester Mackenzie, Joe Mendelsohn and Jean Tschohl Quinn led the “Season of Lamentation” panel discussion at St. George’s Church, Laguna Hills, on Aug. 18. Photos: Jean Klein

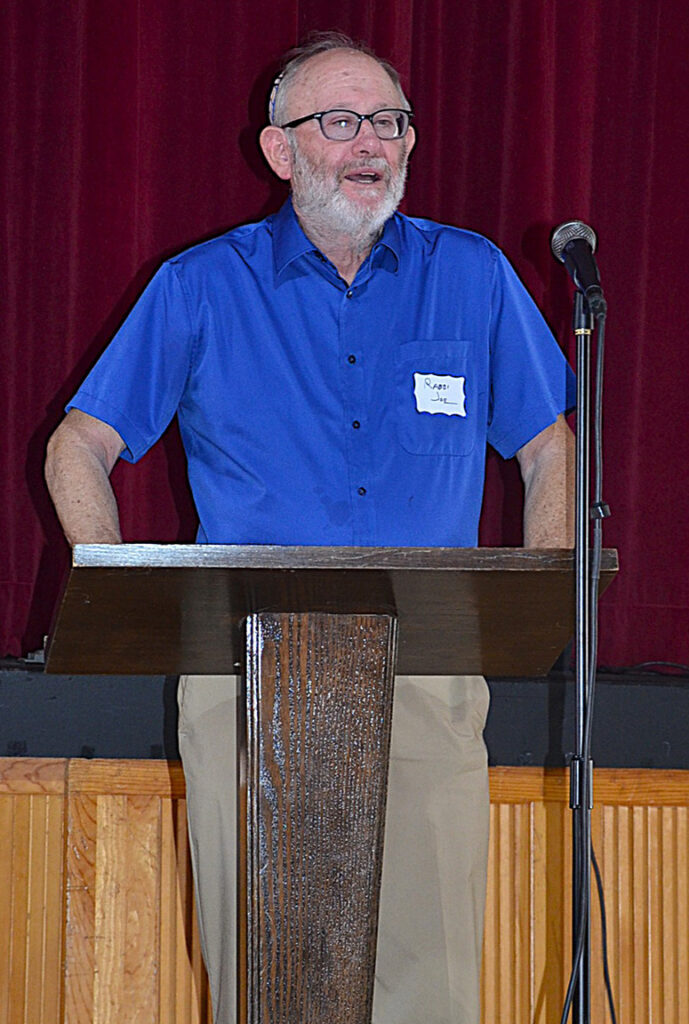

[The Episcopal News – August 21, 2024] A “Season of Lamentation,” an Aug. 18 gathering at St. George’s Church in Laguna Hills, drew participants from across the diocese yearning for common ground and interfaith connection in a conversation led by panelists the Rev. Lester Mackenzie, rector of St. Mary’s Church, Laguna Beach; Jean Tschohl Quinn, chair of the Local Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’i of San Clemente; and Rabbi Joe Mendelsohn of the Reform Temple of Laguna Woods.

The Rev. Vanessa Mackenzie, rector of the Church of the Advent, told The Episcopal News she was willing to brave heavy Sunday afternoon traffic to Orange County from Los Angeles “for an opportunity to dialogue and to listen to and to learn from people of faith with as much diversity as possible.

“It is wonderful to be invited into a sacred space to lament,” about the many challenges today, she said. “When you cry, the whole world cries with you – welcome to the human race.”

Similarly, Amy Clayton, who attends Grace Church in Moreno Valley, said she was drawn to the gathering to share communal grief. “I’ve been doing a lot of grief work. Grief is ephemeral until it hits you in the head,” said Clayton. “It is something you work through; you have to let it teach you. Lamentation seems to be an expression of grief.”

The program was hosted by St. George’s “Loving Our Neighbor” ministry to “focus on learning about our neighbors and hearing their stories along with thinking of ways to heal” from the wrongs of the past as well as the challenges of the present, said Sue Stewart, an organizer.

Inspiration for the interfaith dialogue also grew out of personal experiences with The Episcopal Church’s “Becoming Beloved Community” and “Sacred Ground” programs, Stewart added. “One of the outcomes of Sacred Ground, shared by all the participants, was a need to lament the pain and suffering we had been learning about.”

Sacred Ground is an 11-part film- and readings-based dialogue series focused on Indigenous, Black, Latino, and Asian/Pacific American histories as they intersect with European American histories. Part of the Becoming Beloved Community initiative and a focus of Presiding Bishop Michael Curry’s tenure, Sacred Ground reflects The Episcopal Church’s ongoing commitment to racial healing, reconciliation, and justice locally, communally and globally.

Engaging Sacred Ground led to honoring ethnic and racial diversity in liturgical celebration as well as additional offerings, including “Let’s Talk About Race,” said Colin Stewart, a St. George’s parishioner. “They have helped me understand more about the world around me and the ways that our shared history has created the challenges that we live with today.

“Much that I learned was not anything to celebrate,” he said. “Rather, it was a series of facts that we need to come to grips with as we work to move beyond the shortcomings of the past and the present. A Season of Lamentation is one way to do that as we embrace the hope for a renewed future.”

Panelist Jean Tschohl Quinn, chair of the Local Spiritual Assembly of the Baha’i of San Clemente, leads the gathering in song. Photo: Jean Klein

Panelist Jean Tschohl Quinn told the gathering that while both sorrow and lament are part of human experience, they also present opportunities to forge common bonds.

“Look at Abraham’s sorrow in deciding how to handle the sacrifice of his son,” she said, referring to Genesis 22, in the Hebrew Scriptures. “Or, Jesus Christ, in the garden of Gethsemane. The prophet Muhammad was six years old when he lost his mother to illness. They carried these huge sorrows in their humanness. In this human experience we can relate to one another on a certain level.

“Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Baha’i faith, is no different. He was imprisoned, exiled, tortured, under house arrest for over 40 years; he suffered poisoning. The list goes on and on.”

Bahá’u’lláh, whose name means “glory of God,” founded the Baha’i faith in Iran in 1844 and focused his teachings on unity and religious renewal. Believers consider him to be the latest in a line of messengers from God, including Abraham, Moses, Krishna, Buddha, Zoroaster, Jesus Christ and Muhammad.

Quinn read excerpts from Bahá’u’lláh’s “Fire Tablet,” considered to be his conversation with God, expressing distress over his persecution: “Coldness hath gripped all mankind: where is the warmth of thy love, O Fire of the worlds? Anguish hath befallen all the peoples of the earth: where are the ensigns of thy gladness, O joy of the worlds? … where are the daysprings of purity, O desire of the worlds? … Should all the servants read and ponder this, there shall be kindled in their veins a fire that shall set aflame the worlds.”

Lamentation leads to service, Quinn said. “You can feel the sadness and determine how you can serve others in small and large ways. Don’t waste your time worrying about the judgment of others as you make those choices of light. And cultivate patience, passion for those around, and we can make a better world … Do something. Think love.”

Rabbi Joe Mendelsohn of the Reform Temple of Laguna Woods reminds the gathering to stop and think before speaking to those of different nationalities or faiths to avoid giving unintentional offense. Photo: Jean Klein

Judaism does not dwell on sorrows, but rather on the strength of community, according to panelist Joe Mendelsohn, who noted increases in incivility and hate speech.

Incivility happens daily, he told the gathering, often in unintentional ways, but causes damage nonetheless, he said. For example, at a grocery store a clerk addressed a senior citizen as “sweetie. I could tell from the way she looked at that checker, who was oblivious, who didn’t realize she had been offensive,” he said.

Hate speech also happens in more obvious ways. A friend whose family originally came from China was asked, ‘Why don’t you go back where you came from?’ he recalled. “And she said, ‘Where, Chicago?’ But she knew what was being said: ‘You don’t belong here. You’re not like me.’ It’s a message that is untenable.”

He urged the gathering to “think before you speak. How many times have I been asked, ‘What church do you belong to?’ It’s a wonderful question but … I don’t belong to a church. Buddhists don’t belong to the church. Hindus don’t belong to churches. They are houses of worship. If you’re Christian, that works. But if you don’t know the individual, stop and think before you ask, even though the question was meant in love and respect and you wanted to be inclusive, you could turn around and exclude somebody just with that question.

“We’re supposed to take care of the other, right? The other is your neighbor, your friend. But is other part of we and us, or excluding from we and us? May we all know a little bit more about what hurts someone else and someone else won’t lament. This is our world together. There is no other. There’s only we and us.”

Lester Mackenzie, rector of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Laguna Beach, shared stories of his childhood in apartheid South Africa. Photo: Jean Klein

Lester Mackenzie told the gathering he was born in Johannesburg, South Africa, “and my world view is shaped by apartheid. My world view is shaped by how lamentation becomes a vital tool for the community, to voice suffering, to voice injustice, to voice God’s intervention. Lamentation is less about despair and more about courageously bringing our pain to God, knowing and trusting that God hears.

“In the Christian tradition, lamentation – telling the truth about my pain – is an expression of faith, acknowledging my brokenness while simultaneously opening myself to the grace that I need that God can provide. Lament is not the end, but the beginning of God’s transformation for grace, for you, for me, and so in The Episcopal Church, in the Christian tradition, this aligns with our sacramental theology of confession, absolution and grace.”

Lament is also healing and opens the way to transformation, he said, quoting the late South African Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu: “Without forgiveness there is no future. Lament opens you and me to the grace of forgiveness. If you don’t believe me, go to YouTube and look up the Truth and Reconciliation Commission stories,” he added, referring to South Africa’s reckoning with human rights violations during apartheid.

The TRC’s goals included gathering information, receiving the testimony of victims, publishing a report, examining the findings and promoting reconciliation and forgiveness.

Barbara Van Gasbeek, a St. Mary’s Church parishioner, said she attended Sunday’s gathering as an antidote to rampant conflict and uncivility in the national discourse. “I am so tired of all of it. I came to be educated, to find a way to do something. We need to get together and try.”

Gordon Hill, a member of St. Mark’s Church in Van Nuys, and of the H. Belfield Hannibal Chapter of the Union of Black Episcopalians, said he was hoping to join like-minded people “and to learn and to reaffirm that we are all one in the Spirit.”

Gary Goodman, a member of the Interfaith Council of Greater Rancho Santa Margarita, who attends St. Margaret’s Church in San Juan Capistrano, said such gatherings are important to build unity and to restore hope. “I’ve come to the realization that we’re all in this together. It’s comforting to know that the ‘other’ isn’t really other.”

St. George’s parishioner Kathie Killen said the Sacred Ground, Becoming Beloved Community and Loving Our Neighbor programs “have been a challenging learning experience because loving my neighbor is necessary but not necessarily easy.

“This is why I knew I needed to participate … to face some uncomfortable truths about myself in a safe place with others who were equally vulnerable. Together we’ve sought ways to connect on a deeper level and that is how the Lamentation program came about. My hope is that we’ll continue to discover what binds us and heals us and share that with our communities.

Sue Stewart agreed: “For me, right now, an opportunity to lament the divisiveness in our country and the ongoing wars in the world helps me have some place to put the helplessness I feel.”