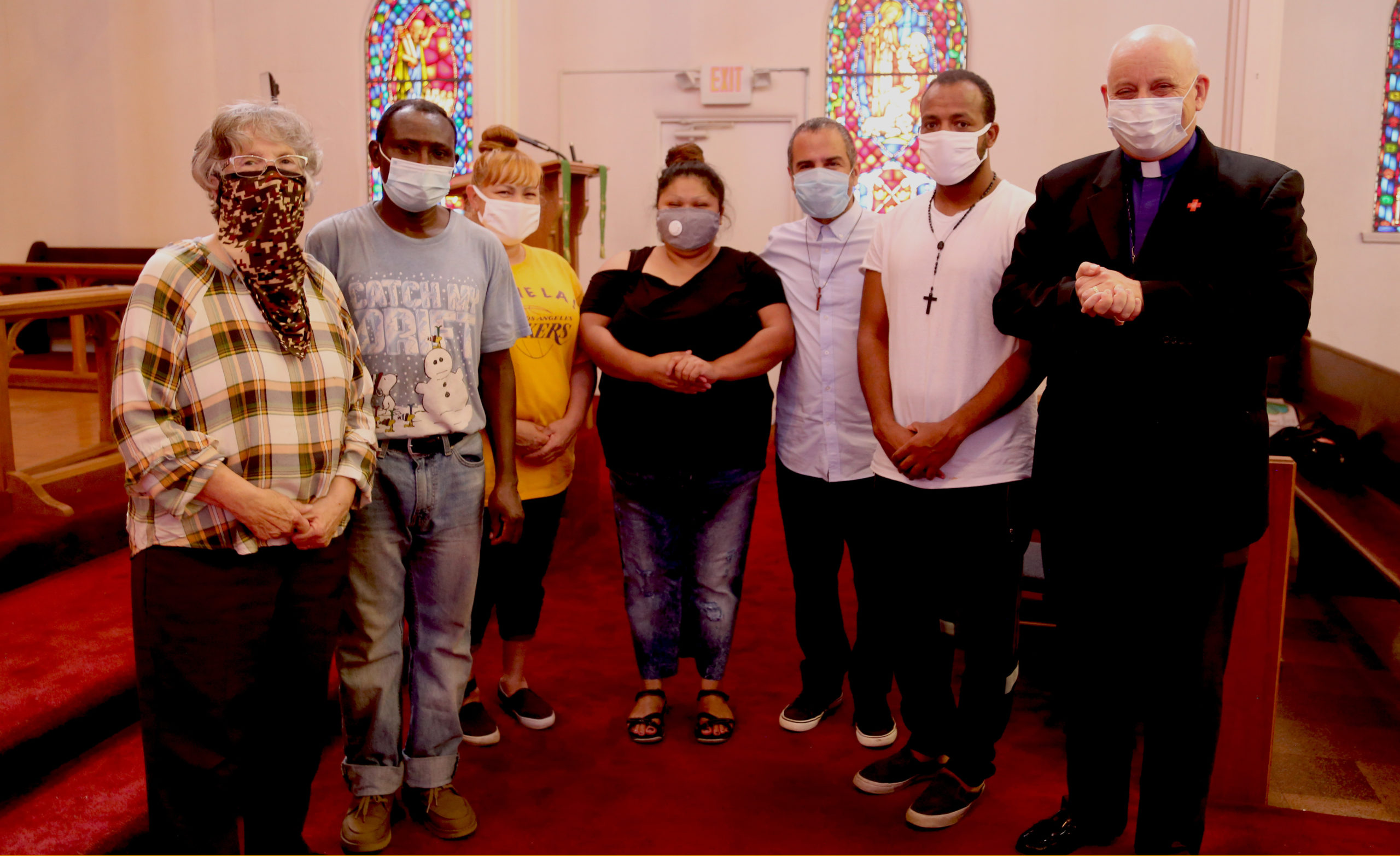

Linda Pederson, vicar, left, Guillermo Torres of CLUE, third from right and Bishop John Harvey Taylor, right, pose with the four asylum seekers now staying at St. John’s Church, San Bernardino. From second right, the asylees are George (from Nigeria), Guadalupe and Maria (from Mexico) and, between Torres and Taylor, Drar (from Eritrea). Photo: Janet Kawamoto

At St. John’s Episcopal Church in San Bernardino, “shelter in place” has taken on a whole new meaning as the parish has become a home for immigrants released on humanitarian parole from detention centers amid coronavirus outbreaks.

More than 50 coronavirus cases have been reported at the Adelanto Detention Center, where George, 79, a Nigerian evangelist, was imprisoned for more than a year after overstaying his visa.

Now he spends his days at St. John’s, sweeping, groundskeeping, and cleaning, “to praise God,” he says.

He dreams of creating an outreach ministry to assist area homeless youth “and to make a difference in this community, this city and this nation, to show other people God is faithful and always there for them.”

He added: “I thank God he brought me here. I am making a new family here. I thank God for using people to be a blessing to me.”

Linda Pederson, deacon at St. John’s, San Bernardino, describes the congregation’s work with asylum seekers. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Those people include the St. John’s congregation, led by the Rev. Canon Linda Pederson; Guillermo Torres, director of the immigration campaign for CLUE (Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice); and Los Angeles Bishop Diocesan John Taylor, who brought them together.

“In the pandemic, some of us are preoccupied with the basic logistics of family, church and our business lives; but virtually invisible, not only in our lives but increasingly in the news, are tens of thousands of asylees in an unjust and not-well-overseen or policed detention system nationwide,” Taylor said during a Sept. 28 visit to St. John’s.

“Our partners in the Diocese of Los Angeles are continuing to look for ways to collaborate on behalf of the gospel of Jesus Christ, on behalf of those most at need among us.”

A video report on the ministry is here.

Torres is calling upon local congregations to join the “Shelter in Place Immigration Freedom Project” he created and, like St. John’s, to convert classrooms and other unused space to protect and house former detainees from coronavirus outbreaks in detention facilities. “Since most churches are not having current physical gatherings right now, opening up just one space will be ideal to help provide housing for a brother or sister,” Torres said.

Activist and organizer Guillermo Torres of CLUE explains how congregations can use empty classrooms or other spaces to shelter refugees, who must have housing before they can leave what he called “horrific” conditions in detention centers. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

“You could save a life, set somebody free from horrible conditions in detention centers,” he said. “Through Bishop Diocesan John Harvey Taylor, we got in touch with St. John’s. The diocese has been part of the Sanctuary Movement for a long time. This is not a homeless shelter; if they don’t have a housing sponsor, they can’t get out. If people in detention don’t have an address or a home to go to, they cannot get humanitarian parole.”

A federal judge allowed the start of a bail process as part of a class-action lawsuit filed by the ACLU of Southern California. The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) had appealed the order to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. That appeal was recently denied, paving the way for detainee release.

Among the conditions at the prison cited in the ACLU suit were inadequate sanitation, beds placed too close together, and lack of proper safety protocols, creating the potential for rapid spread of the coronavirus.

“I am so thankful for a home,” George told The Episcopal News. “In Adelanto, we were treated as animals. We are human beings.”

Church uses empty classrooms to shelter former detainees

St. John’s represents the first larger scale partner to house former detainees, Torres said. The church’s food pantry, open to the community most Wednesdays, is an added benefit, but congregations housing detainees also are aided with donations through CLUE’s network of partnerships.

“It is a great honor that we can serve our neighbors with our food pantry and use our empty classrooms and giant kitchen to make people welcome here,” said Pederson, a deacon who serves the congregation as vicar. “They are able to enrich our congregation and it’s been wonderful for our members to meet them, talk with them, and share in their stories.”

CLUE assisted St. John’s with making repairs, painting and readying unused classrooms. Bedding, linens, appliances, personal care items and gift cards were donated, she said.

Guadalupe and Maria talk about the fears that drove them to seek refuge in the United States from their native Mexico — and how safe they feel at St. John’s. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Currently, St. John’s hosts George and three other residents: Guadalupe and Maria, both originally from Mexico, and Drar, who was born in Eritrea and spent eight months at Adelanto. The church has a total of 10 beds, Pederson said.

CLUE receives referrals from immigration attorneys and works with its partners to place detainees in safe environments, Torres said. “When you’re an asylum seeker, you don’t have family or friends, especially after fleeing your country because of violence, extreme poverty, or other issues” he said.

Relocating detainees has been more complicated because Covid-19 pandemic has made many families less willing to open their homes to strangers, he said. He pleaded with churches to “let us use your buildings. Let us sponsor housing for an immigrant.”

Accommodations at St. John’s are simple, but comfortable, with donated furniture, bedding and other necessities — and refugee residents quickly make them their own. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

For Guadalupe, living at St. John’s represented a special homecoming. “I lived in San Bernardino a long time ago.” After living in the U.S. for 33 years, she found herself detained at Adelanto. “It was a hard place for me to be,” said Guadalupe, who wears an ankle monitor.

The Adelanto Detention Center is a privately-owned center located in Adelanto, in San Bernardino County, housing nearly 2,000 immigrant detainees. It is owned and operated by the Boca Raton, Florida-based GEO Group invests in private prisons and mental health facilities in North America, the United Kingdom, Australia and South Africa. GEO reported a 2019 net income of $166 million.

“GEO is making money off the suffering of immigrants,” Torres said. “This program sets the captive free, freeing them from possible death and even more suffering at Adelanto.”

A GEO group spokesperson has said the company has taken “comprehensive steps” to mitigate the risk posed by the coronavirus pandemic. “We strongly reject these unfounded allegations, which we believe are being instigated by outside groups with political agendas,” the spokesperson added.

CLUE has collaborated with a host of partners to launch the Shelter in Place program, including Taylor and the diocesan Interfaith Refugee and Immigration Service (IRIS), which has provided legal resources, Torres said. The Shelter in Place Immigrant Freedom Project, he believes, can “show the government there are humane alternatives to shelter immigrants. They should not be locked up in detention centers.”

Bishop John Harvey Taylor chats with refugee housing resident Guadalupe on Sept. 28 at St. John’s Church, San Bernardino. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

“We are grateful they have walked along with us,” Torres said. “To walk in solidarity, to join the voices of those clamoring for freedom and justice — not to speak for them. Immigrants have their own voices but sometimes we don’t listen. We are amplifying their voice for justice, freedom and being in this space for them, but they have to have their own voices.”

Pederson said St. John’s hopes to strengthen assistance to their guests. “We hope to provide classes, through other agencies, to work on their English, legal documents and possible job prospects.”

At St. John’s, both Maria and Guadalupe said they feel safe to share their voices, and to tell their stories.

“We came here for help,” said Maria, through a translator. She added, tearfully: “We came here for help. We don’t come here to take nothing from nobody. We just want to be better, to work. I appreciate Miss Linda so much. They opened the doors for us to be safe and to have a place to stay and we appreciate it very much.”

For information about the Shelter in Place project, contact Torres at gtorres@cluejustice.org or 323.228.2753.

Bishop John Harvey Taylor leads vicar Linda Pederson, CLUE organizer Guillermo Torres and the four refugee residents of St. John’s in a prayer. Photo: Janet Kawamoto