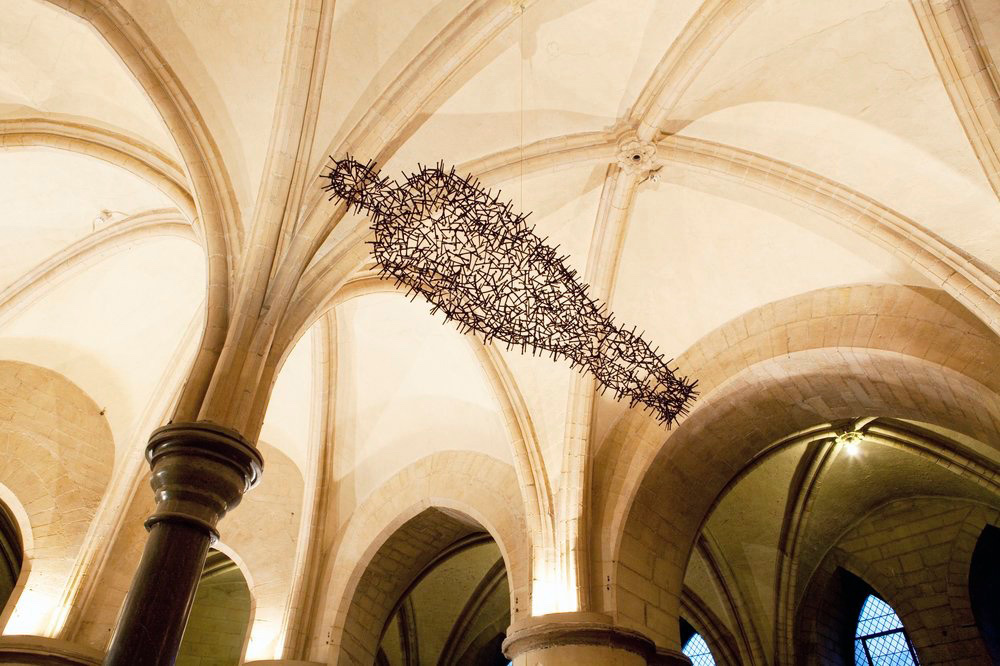

The most arresting sight in Canterbury Cathedral, especially at night, is a sculpture by Antony Gormley called “Transport.” It’s a little over six feet long, in the form of a human body, fashioned from 210 large black nails, some pointing in, others out, evoking the swords used to kill Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket as well as the hair shirt the monks found he was wearing when he died.

It also conveys a sense of betwixt and between. It’s suspended about 12 feet over the site of Becket’s original tomb. He was assassinated four days after Christmas Day in 1170 by knights who had been led to believe that Thomas’ childhood friend Henry II wanted it done. Perhaps another 12 feet above it is Trinity Chapel, where Thomas’s body lay from 1220 until Henry VIII desecrated the tomb and ordered Thomas’ bones destroyed in 1538. The cathedral keeps a candle lit for Thomas on the chapel floor.

It also conveys a sense of betwixt and between. It’s suspended about 12 feet over the site of Becket’s original tomb. He was assassinated four days after Christmas Day in 1170 by knights who had been led to believe that Thomas’ childhood friend Henry II wanted it done. Perhaps another 12 feet above it is Trinity Chapel, where Thomas’s body lay from 1220 until Henry VIII desecrated the tomb and ordered Thomas’ bones destroyed in 1538. The cathedral keeps a candle lit for Thomas on the chapel floor.

“Transport” hovers between those two spots. One evening last week, the Rev. Dr. Emma Pennington, the cathedral’s canon missioner, took 20 of us Lambeth Conference pilgrims on a candlelit tour. (Many more got the same opportunity during the conference.) We started in the Nazareth Chapel in the crypt, which dates from Norman times. Here Emma spoke soothingly about Julian of Norwich, one of her other specialties, and invited us to pray about our ministries and the people we love. She kept stressing that it was our spiritual home, as bishops and spouses, as Anglicans and Episcopalians, wherever we are.

Then she led us to the site of Thomas’s first tomb, which had an opening that permitted pilgrims to touch his body, and shined her flashlight on “Transport,” casting eerie shadows on the stone walls. She and her colleagues had asked us not to take photos during the tour. We just held our candles, and after a few minutes, the rising heat made the sculpture move. Its disquiet was a sight to remember. I read later that the nails the sculptor used were from medieval times, preserved after a roof was repaired. If walls could talk and nails exclaim. Were they in place, holding the cathedral together, when Thomas was killed? Or when Henry VIII tried to erase his name from history? “This is holy ground,” T.S. Elliot wrote in Murder in the Cathedral, “and the sanctity shall not depart from it.”

Then she led us to the site of Thomas’s first tomb, which had an opening that permitted pilgrims to touch his body, and shined her flashlight on “Transport,” casting eerie shadows on the stone walls. She and her colleagues had asked us not to take photos during the tour. We just held our candles, and after a few minutes, the rising heat made the sculpture move. Its disquiet was a sight to remember. I read later that the nails the sculptor used were from medieval times, preserved after a roof was repaired. If walls could talk and nails exclaim. Were they in place, holding the cathedral together, when Thomas was killed? Or when Henry VIII tried to erase his name from history? “This is holy ground,” T.S. Elliot wrote in Murder in the Cathedral, “and the sanctity shall not depart from it.”

We reached Trinity Chapel using stairs rounded by tens of millions of pilgrim feet over the course of 800 years. Behind it is the Corona Chapel, once home to a reliquary containing a piece of Thomas’s skull (corona being a reference to the severed top of Thomas’s head). Then to a spot called the Martyrdom, where the knights killed him gruesomely (look it up if you want) as he and the monks chanted vespers. A few feet away is the door the assassins used to get in after Thomas insisted it be unlocked as befitted, he said, a house of God.

We reached Trinity Chapel using stairs rounded by tens of millions of pilgrim feet over the course of 800 years. Behind it is the Corona Chapel, once home to a reliquary containing a piece of Thomas’s skull (corona being a reference to the severed top of Thomas’s head). Then to a spot called the Martyrdom, where the knights killed him gruesomely (look it up if you want) as he and the monks chanted vespers. A few feet away is the door the assassins used to get in after Thomas insisted it be unlocked as befitted, he said, a house of God.

It didn’t have come to that. Henry and Thomas famously differed over how to discipline members of the clergy. If a priest murdered someone, to offer an extreme example, Thomas still wanted it left to ecclesiastical courts. The old friends were in the laborious process of working things out when, in June 1170, Henry arranged to have bishops not including Thomas crown his and Eleanor’s eldest son as Henry’s successor. He was enraged when Thomas, who considered coronations to be Canterbury’s prerogative, excommunicated the bishops.

It was yet another tussle between church and state. In the matter of Henry vs. Thomas, the score is betwixt and between. If a priest or pastor robs a bank these days, someone’s going to call a cop. But when it comes to heinous abuse, all too often the church has kept it all in its own court, leading to cover-ups and more abuse. As for coronations, Thomas won that round decisively. The archbishop of Canterbury gets the job every time. Should Queen Elizabeth decide to step down in the next few years, several hundred of us just shook the hand that will anoint the next king of England.

It was yet another tussle between church and state. In the matter of Henry vs. Thomas, the score is betwixt and between. If a priest or pastor robs a bank these days, someone’s going to call a cop. But when it comes to heinous abuse, all too often the church has kept it all in its own court, leading to cover-ups and more abuse. As for coronations, Thomas won that round decisively. The archbishop of Canterbury gets the job every time. Should Queen Elizabeth decide to step down in the next few years, several hundred of us just shook the hand that will anoint the next king of England.