Charlie Munger, who died in November within sight of his 100th birthday on Jan. 1, fell ill at his home in Santa Barbara. When he got to the hospital, a nurse asked him how he was. “I’m dying,” he said. “How are you?”

Charlie Munger, who died in November within sight of his 100th birthday on Jan. 1, fell ill at his home in Santa Barbara. When he got to the hospital, a nurse asked him how he was. “I’m dying,” he said. “How are you?”

His daughter Emilie Munger Ogden told the story Sunday afternoon during his family’s beautifully organized celebration of life at Harvard-Westlake School, which he served for 54 years as a trustee and its most generous single benefactor. Kathy and I were along with hundreds of his family and friends, including The Parish of St. Matthew – The Episcopal Church in Pacific Palisades friends Rob and Colleen Wood.

Emilie also said he placed a call from his hospital bed to Warren Buffett, his friend since 1959 and longtime business partner. During the service, Buffett’s daughter, Susie, said the two native Nebraskans, self-proclaimed agnostics, developed an instant man crush. At investing giant Berkshire Hathaway, she said, quoting her father, Warren is the builder, but Charlie was the architect.

The two-hour service allowed plenty of time for Charlie’s famous aphorisms. “You can’t guarantee happiness,” he said. “But you can guarantee misery.” Another daughter, Wendy, said his chief questions were “what the hell is going on here?” and “why the hell is it happening?” Clarity and truth were persistent themes. Famously impatient with ideology and cant, Charlie was know to believe that people in denial always make bad decisions. He called the best relationships “seamless web(s) of deserved trust.”

The two-hour service allowed plenty of time for Charlie’s famous aphorisms. “You can’t guarantee happiness,” he said. “But you can guarantee misery.” Another daughter, Wendy, said his chief questions were “what the hell is going on here?” and “why the hell is it happening?” Clarity and truth were persistent themes. Famously impatient with ideology and cant, Charlie was know to believe that people in denial always make bad decisions. He called the best relationships “seamless web(s) of deserved trust.”

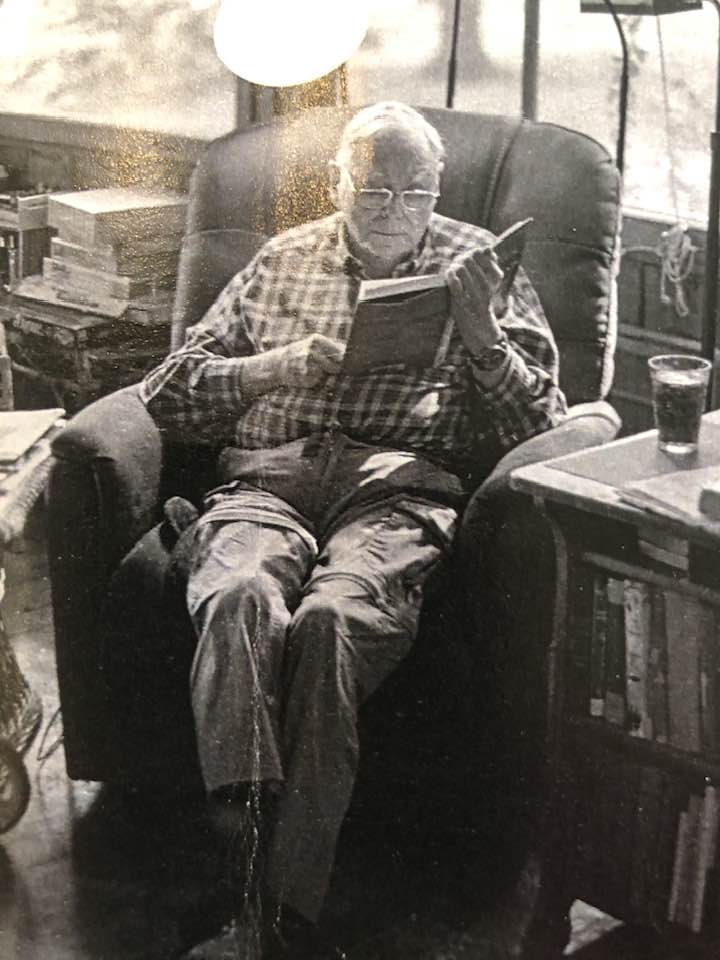

Speaking of Charlie and his second wife, Nancy (also the name of his first), their son Philip Munger’s voice cracked when he said, “My mother and my father were a home for each other.” In a video, a parade of adorable grandchildren and great-grandchildren repeated favorite words of Charlie’s such as twaddle, kapow, skedaddle, and wise-assery. Members of older generations said they were used to seeing him with his nose in a book. In a montage screened before the service, a half-dozen photos showed him reading.

I remember him praising Jon Meacham’s Lincoln biography when we spoke on the phone a couple of years ago. We served together on the boards of Harvard Westlake and Good Samaritan Hospital (he was its devoted and epically generous chair when it was still part of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles), and so from time to time I called for advice and political talk. When I said we wanted to build affordable housing, including for commuter students, on 25% of our church campuses, he made my heart sing by saying it wasn’t the dumbest idea he ever heard.

I remember him praising Jon Meacham’s Lincoln biography when we spoke on the phone a couple of years ago. We served together on the boards of Harvard Westlake and Good Samaritan Hospital (he was its devoted and epically generous chair when it was still part of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles), and so from time to time I called for advice and political talk. When I said we wanted to build affordable housing, including for commuter students, on 25% of our church campuses, he made my heart sing by saying it wasn’t the dumbest idea he ever heard.

Charlie died on Nov. 28, a Tuesday. On the Saturday before, his daughter-in-law Mandy Lowell emailed and asked me to call him on her cell phone in Santa Barbara, which I promptly did, though we didn’t connect. I’ll always be a little curious about that. With a large personality such as his, curious enough to inquire about someone else’s well-being from his deathbed, it could have been anything. We learned Sunday that someone once asked if he knew how to play the piano. “I don’t know,” he said. “I’ve never tried.” Yet he tried and finished so much in his century. Imagine what he is making of eternity.