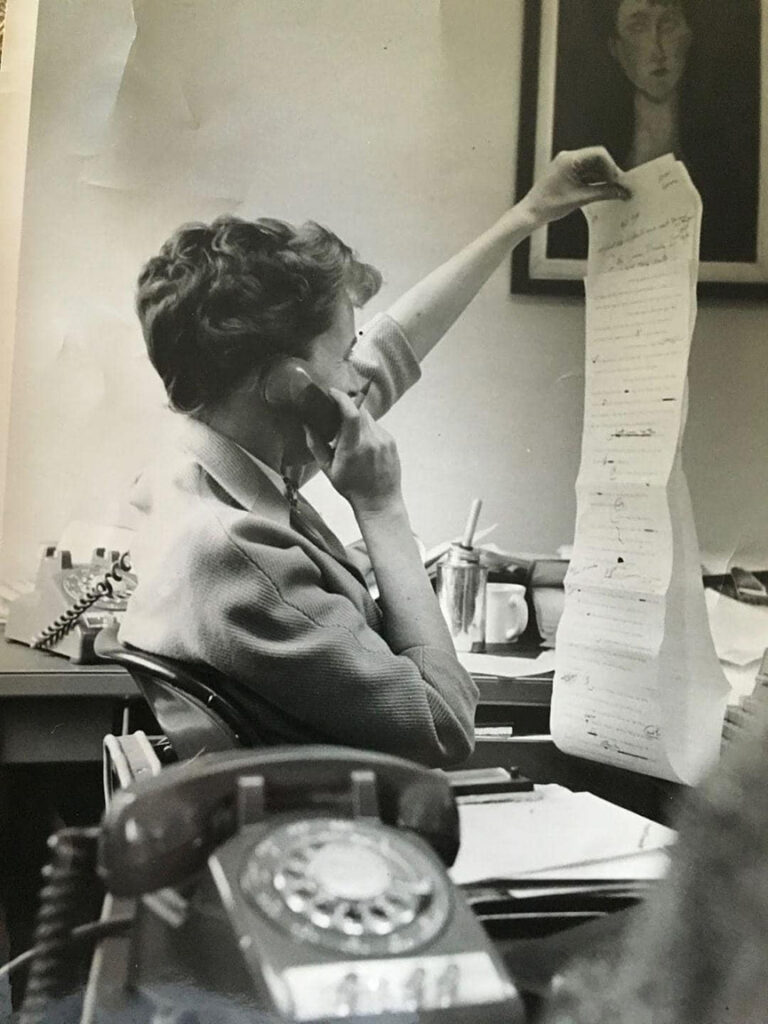

My mother the newspaper editor, launched by Hudson’s.

It’s hard to read the raw statistics without cringing. Sixty percent of the U.S. population is white but just 30% of those in federal prison. Just over 12% of us are people of African descent compared to nearly 35% of prisoners.

People don’t vary according to race in their moral and ethical capacity, although I fear some are still tempted to think otherwise. The only explanation for the disparity is the hard truth that we haven’t reckoned fully with the sins of slavery, Jim Crow, and continuing racism. It’s been 159 years since the Union army arrived in Galveston on that June 19 and proclaimed that Texas’s quarter million enslaved people were free. Let’s break down the walls of the jails and prisons and set free those held unjustly in our time.

It’s a matter first of all of basic human decency. Jail and prison chaplains give us chapter and verse about appalling conditions behind bars. U.S. justice metes out harsh retribution. Those who favor reform and rehabilitation get drawn into wearying arguments about victims’ rights and crime rates. But one can support sending deserving criminals to jail without losing sight of the way prejudice and the iron laws of socio-economics lay disproportionate burdens on the shoulders of young men of color, especially those of African descent. It exacerbates the indecency when we beat the scales of justice into a sword of vengeance.

We all share the urgent responsibility for breaking this cycle of injustice. But how many of us even notice it? Doing so requires white people to do our personal, sometimes unpleasant Juneteenth work.

Here’s mine. At 17, in the late forties in Detroit, when racism was rampant, my mother got a job at a department store. I think of all the Black girls who didn’t have the same shot. My alcohol-addicted father left us when I was two. By then, my mom could afford a babysitter. As a teenager, I was thoughtless and irresponsible. I came home alone after school because my mom worked long hours. But by that time, we had a nice house in a safe neighborhood. At 15, though I wasn’t really qualified, I was admitted to an elite boarding school where my dad had an ancient family connection.

One leg up after another, and I finally straightened out. People mature at different rates. It’s not that I didn’t deserve grace. But millions of Black children deserved it, too. I am not confessing a hidden criminal temperament. But I came home to an empty house on a hill instead of crowded neighborhood where somebody might have led me into an alley, handed me a joint, and redirected my life. Sheer logic suggests that if I had fallen into the wrong circles in adolescence, the victim, one must say, of neglectful or distracted parents and my own diffidence, I could’ve been in prison, too. Some readers who also grew up in privilege may insist that they would have had the character to withstand the chaos of urban poverty. But common sense and our Christian faith insist that we are all equally fallible.

I don’t like thinking or writing about this. It would be easier to lift up my mother’s hard work and proto-feminism as a pioneering reporter and editor. But that narrative leaves no room for the equally qualified 17-year-old Black girls in Detroit who didn’t get mom’s all-important first job at the J.L. Hudson Co. Millions on millions of such moments begat the horrifying statistics with which I began.

And yet here’s another troubling score as hundreds of us Episco-Pals set our sights for the 81st General Convention of The Episcopal Church in Louisville, which begins Friday: 16-2. The Episcopal News Service reports that we will consider at least 16 resolutions on Israel and Palestine. I’m involved in that work myself, and while I don’t underrate its importance, I don’t expect we will have much impact on the course of events. In contrast, by my count, we have just two resolutions on prison reform — odd, when you think about it, since one might argue that we have an occupied West Bank of our own, namely millions of incarcerated people whom we have made victims of our blindness to our society’s lingering inequities.

Both resolutions are serious and substantive. If passed, C010 would recommits the church to federal prison ministry. Painting with perhaps too broad a brush, D034 calls for the abolition of the police and prison system as a racist artifact. Its eloquent authors tend to look askance at the incrementalist reforms I’d prefer, beginning with freeing and providing treatment for all whose misconduct was a consequence of mental illness or addiction and putting white collar convicts to work in non-profits and churches.

And yet I agree with every word of D034’s fourth paragraph: “That this Convention affirm that Jesus proclaimed freedom for prisoners (Luke 4:18) and promised the possibility of justice aimed at restoration even for those who murdered him (Luke 23:34), and thus that our baptismal vow to ‘proclaim by word and example the good news of God in Christ’ calls us to proclaim God’s desire for liberation for all who are incarcerated and for real justice and accountability that restores relationships, transforms situations of harm, and aims at reconciliation, which is the core mission of the Church.” Bidding you Juneteenth blessings, I say Amen!