As we prayed over the Rt. Rt. John Mark Haung Godia, Anglican Church Of Kenya, Maseno West Diocese.

As the 15th The Lambeth Conference comes to an end on Sunday, as much as I’ve enjoyed this mountaintop experience with sibling bishops around the world and The Episcopal Church, I occasionally found myself wondering where everyone else was — as in the deacons, lay leaders, and priests.

It was a feeling not unlike a moment 30 years ago, during my time with Mr. Nixon. I was his staff support and guest at a retreat in northern California, famous for its three-week-long male-only summer encampment (as well as for writing stern letters to guests and attendees who mention the organization by name). Movers and shakers all, as in foreign ministers and CEOs, and of course former and occasionally even sitting presidents. One camp was famous for jazz music. So there I was under the stars on a Friday night, smelling the pines, sipping wine, and listening to George Gershwin songs with a bunch of dudes and asking myself, “Where is everybody?”

Of course I wasn’t a mover or shaker. But bishops are, all 650 of us from 165 countries, at least in our systems back home. The historic episcopacy is understood as an apostolic succession from the beginning of the church. Try as we will to deconstruct it, it is thick with hierarchy and patriarchy. In some parts of the world where bishops are more conservative, they are almost always male, which can’t help but interfere with mutual understanding when it comes to issues of orientation and identification. While this conference placed stress on spouses as bishops’ partners, they weren’t asked to speak in bishops’ plenary sessions except in a pre-taped video or two. Spouses of gay bishops were kept away from formal sessions. The vast majority of spouses are women, most of them mothers. One can only imagine the conversation about orientation and identification in the bishops’ plenaries if women were free to speak and speak freely.

Many bishops’ local systems also hoist them onto pedestals that most missions and parishes in the United States, I suspect, have long since stored in the closet with boxes of 1940 hymnals. At receptions after confirmation services, these Global South bishops are usually seated at the top table. Whereas I yak so much in the receiving line that sometimes, by the time I get to lunch, there are no seats left, and the potato salad’s gone.

Which is actually the way it’s supposed to be. It is good to remember the bit about how the first should be last. One bishop from Africa said that he tries to relate to his folks more democratically by arriving early, before the lavish receiving ceremony is set up, mingling as much as he can, and staying late. But there, here, and everywhere, old patterns are hard to change.

Many Global South bishops have the added responsibility of playing more prominent roles in regional and national politics, and sometimes riskier roles, than most of us do in the U.S. Their churches are larger and more influential. The considerable contingent of Kenyan bishops are leaving a day early because they want to be home by Tuesday’s presidential election. They want to do everything they can to keep things calm and their people safe.

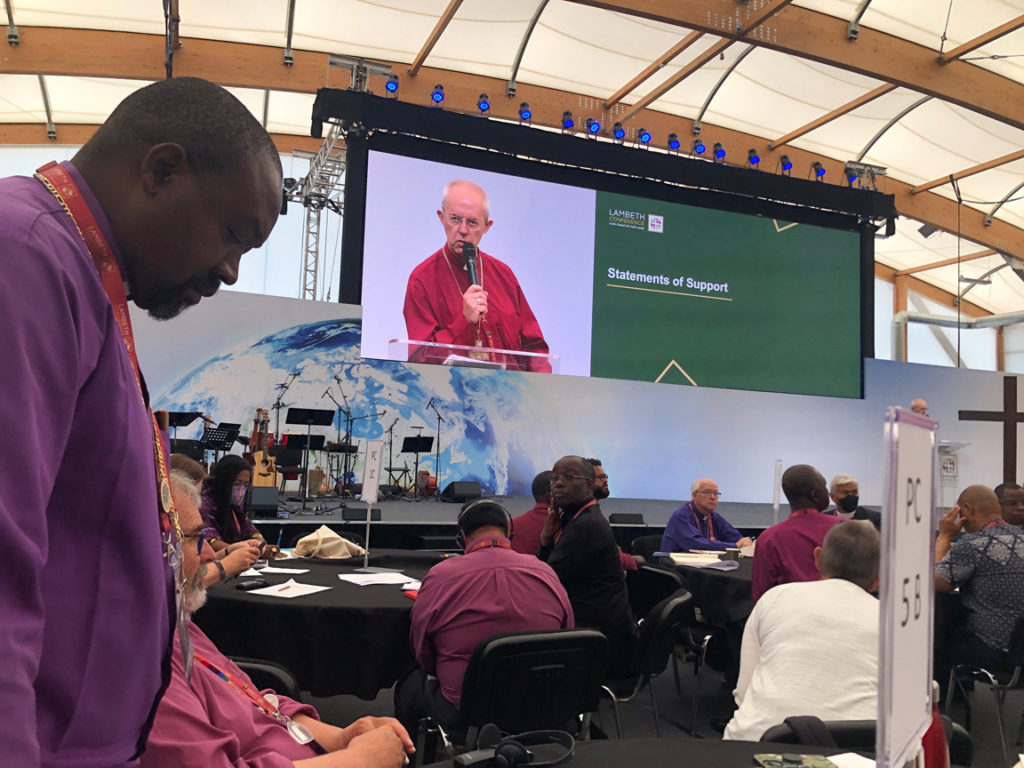

And God’s people are so vulnerable around the world. The conference sometimes felt like the world writ small. As chaotic as U.S. politics seem, as fragile as our democracy may be, we TEC bishops were largely onlookers this morning as Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby moderated an hour of testimony about unrest, injustice, or persecution of Christians. Stories from Congo, Nigeria, Israel and Palestine, Egypt, Sudan, South Sudan, Ukraine, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Tanzania, Afghanistan, Iran, El Salvador, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Brazil, Kenya, and the Philippines. Refugees and migrants everywhere.

The United States was not silent. Presiding Bishop Michael B. Curry submitted an eloquent statement about U.S. gun violence (lifting up Bishops/Episcopalians United Against Gun Violence). But in our quiet, uncontentious hour of prayer, we felt present with tens of millions at risk through the witness of bishops who walk with them daily. If Welby wanted to keep the conference from breaking down over marriage equity, it was because he believes in the unity of the Anglican Communion not for unity’s sake but so our global church can be chaplain to a world in agony.

I leave convinced that this conference was well worth the effort. The Lambeth Calls we adopted will keep Welby busy for the rest of his tenure and the rest of us until Christ comes back — mission and evangelism, safe church, Anglican identity, reconciliation, human dignity (including its deft and historic Shanghai Communique-like language on marriage equity), environment and sustainable development, Christian unity, interfaith relations, intentional discipleship, and science and faith.

It is all magnificent stuff. But more than once this week, I thought of the missing voices in this roughly decennial summer encampment of just bishops, this artifact of Victorian England. At our church’s general convention, the house of deputies is understood to be the senior house. At diocesan conventions of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles, all orders have equal voice. These deserve to be called synods. Lambeth can’t ever be, because of the risk of the imposition of an unacceptable majority view on an issue such as marriage equity but also, perhaps especially, because, well, we’re just a bunch of bishops.