In Willa Cather’s “Death Comes for the Archbishop,” published in 1927, Bishop Latour, patterned after the real-life first bishop of Santa Fe in the late 19th century, sets out through the Arizona and New Mexico desert with his friend, a Navajo chief named Eusabio. I covered some of the same ground earlier this week when I drove to Santa Fe from Window Rock, capital of the Navajo nation.

Our fictional pair were riding mules. Each time they broke camp, Eusabio buried the remnants of their fire and meals. If they’d moved stones or scooped sand, he put everything back. Cather wrote this (and please remember she did so out of a century-old ethos, using the diction of her day): “Father Latour judged that, just as it was the white man’s way to assert himself in any landscape, to change it, make it over a little…it was the Indian’s way to pass through a country without disturbing anything; to pass and leave no trace, like fish through the water, or birds through the air.”

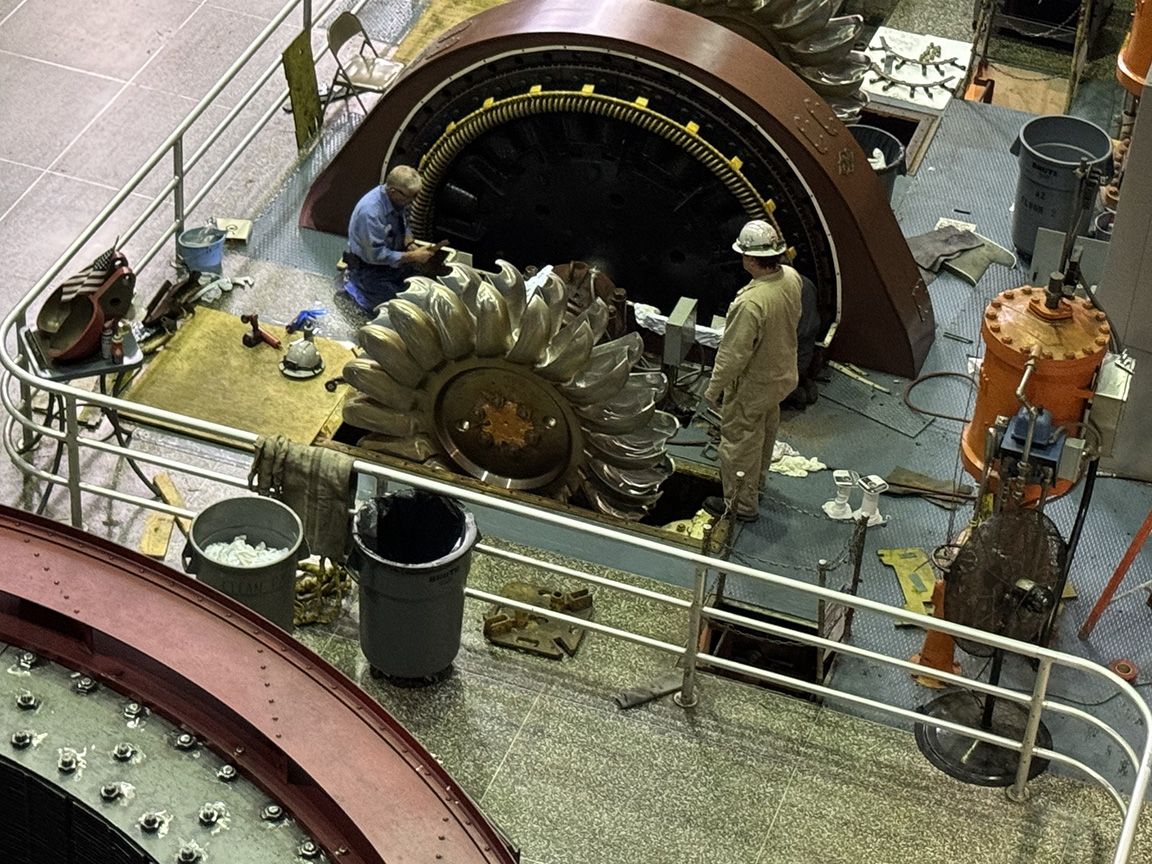

Make it over a little, or a lot. One of my first stops on my week-long swing-state tour was the Hoover Dam, where it took two years to pour over three million cubic yards of concrete. It wasn’t Eusabio’s style. But it makes life easier for tens of millions. It sends electricity to three states. Over half its power is used in the dioceses of Los Angeles and San Diego. But with progress always come tradeoffs. By controlling flooding along the Colorado River and enabling irrigation, the dam helped growers while disrupting ecosystems and the lifespans and sometimes the very existence of animal, fish, and plant species that had been thriving before someone thought to pour all that concrete into Black Canyon.

Make it over a little, or a lot. One of my first stops on my week-long swing-state tour was the Hoover Dam, where it took two years to pour over three million cubic yards of concrete. It wasn’t Eusabio’s style. But it makes life easier for tens of millions. It sends electricity to three states. Over half its power is used in the dioceses of Los Angeles and San Diego. But with progress always come tradeoffs. By controlling flooding along the Colorado River and enabling irrigation, the dam helped growers while disrupting ecosystems and the lifespans and sometimes the very existence of animal, fish, and plant species that had been thriving before someone thought to pour all that concrete into Black Canyon.

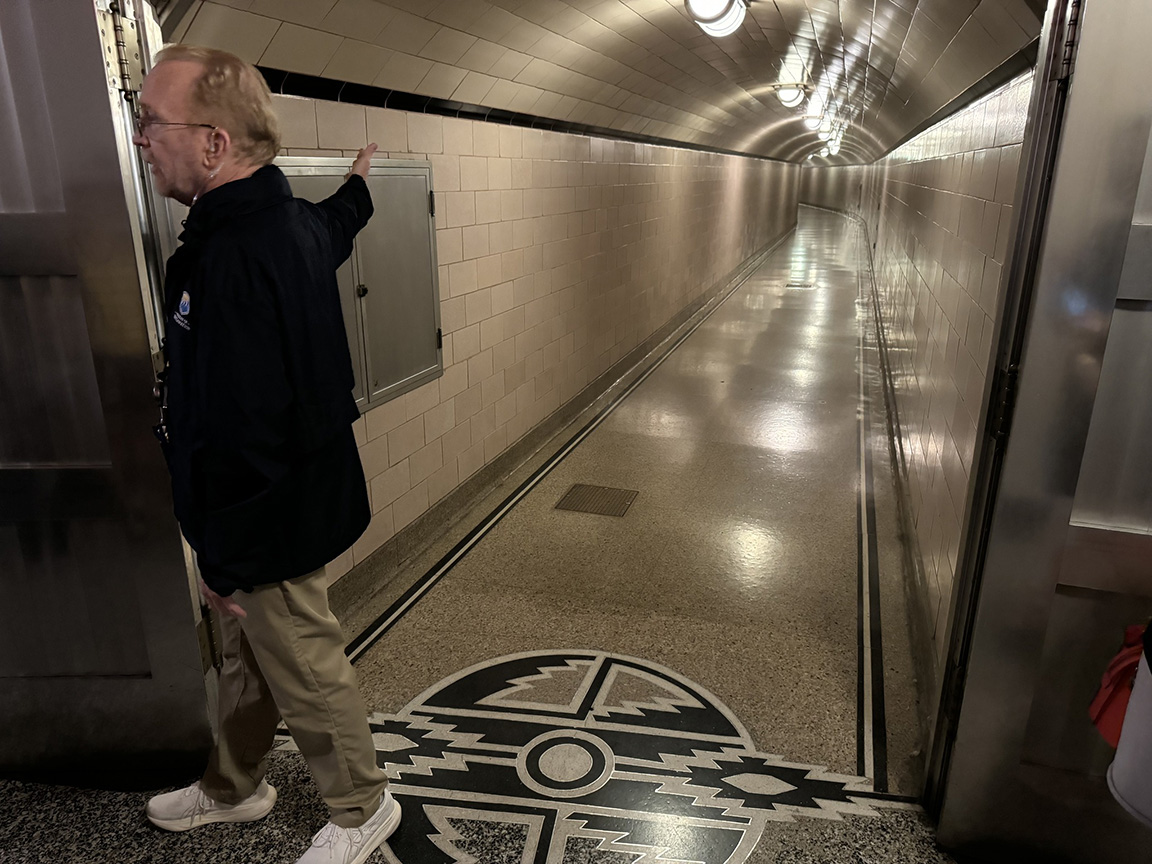

And yet, in its way, it’s beautiful, the way downtown Los Angeles looks beautiful against the San Gabriels, or Air Force One as it lands, especially when it’s bringing visitors who, we trust, are doing the best they can for the largest number of our people. As they cheerfully belabored the same pun (“I hope you enjoyed your dam tour”), our docent guides were proud to be part of a really big dam story, every one of its technical and Art Deco touches. I asked one what he meant when he said it would take some of the concrete another 20 or 30 years to cure. Dry out, that means, when the dam becomes completely stable. Imagine that: Water molecules still holding their own under all that weight, in all that darkness. There’s a baptism sermon living in there, too.

Our guide also told us that, without the use of computers, they had overbuilt the dam by 60 or 70 percent. Better safe than sorry, though it would make Eusabio wince again. I thought of him on Friday as I took the long way from temperate Gallup to the Sonoran Desert climes of southern Arizona, enabling another long look along the Salt River. No doubt disruptive to ecosystems in its own way, its dam system enhances life in Phoenix, where my mother and I spent four years a half-century ago. All these tradeoffs are open for discussion. If saving the planet means finding gentler ways to live, so be it. We should, and we shall.

But these days, we should also worry about our human ecosystems. During this latter leg of my journey, I actually started to feel a little self-conscious about my license plate. When I stopped for Mexican food in Show Low, every car in the lot besides mine was a pickup. A guy waiting for his food inside wore a t-shirt that said “Don’t California my Arizona.” Down the street, the Trump gift shop and headquarters for like-minded candidates took up half a block. One Trumpy state senate candidate’s sign said she was for election integrity.

Based on the company she’s keeping, I have no doubt she’s for the exact opposite. But I caught myself as I began to argue with her out loud as I drove south down the 60. I hope I’m not the only one who does that sometimes. Because what would Eusabio say, he who feared to move a rock or leave empty a hole he’d dug in the sand? Cather’s not here, but having spent much of my journey with her, I can make a pretty good guess. Her character would say that we can always afford to be gentle, that courage and kindness needn’t be incompatible. He would counsel us to take people as we find them. Protect ourselves, of course, but don’t judge until you’ve heard their story. Listen to what they teach before teaching what you know. You can’t change them. Only the Spirit can do that. And the Spirit is at work on you, too. Dam straight.