As I arrived in Santa Fe the other evening, Archbishop Jean Marie Latour was on his deathbed — on books on tape, that is. Thanks to a gloriously apt suggestion from a Facebook friend, Jean and his vicar, Fr. Joseph Vaillant, the main characters in Willa Cather’s 1927 book “Death Comes for the Archbishop,” had been my companions as I drove east through Arizona and New Mexico.

As I arrived in Santa Fe the other evening, Archbishop Jean Marie Latour was on his deathbed — on books on tape, that is. Thanks to a gloriously apt suggestion from a Facebook friend, Jean and his vicar, Fr. Joseph Vaillant, the main characters in Willa Cather’s 1927 book “Death Comes for the Archbishop,” had been my companions as I drove east through Arizona and New Mexico.

I was coming to the end of my day’s drive, and Bishop Jean’s end, right on time. I was especially eager to get to the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi, centerpiece of old Santa Fe, and see the evening sun play against its famous sandstone facade. I’d just read about the fictional bishop discovering the stone himself a few hours’ mule ride to the south.

Sure enough, here was the mighty church, glowing like butter and maple syrup on Denny’s pancakes. Which is why it was a little disconcerting to find out that, these days at the cathedral, perhaps depending on whom you ask, Latour’s name is adobe mud.

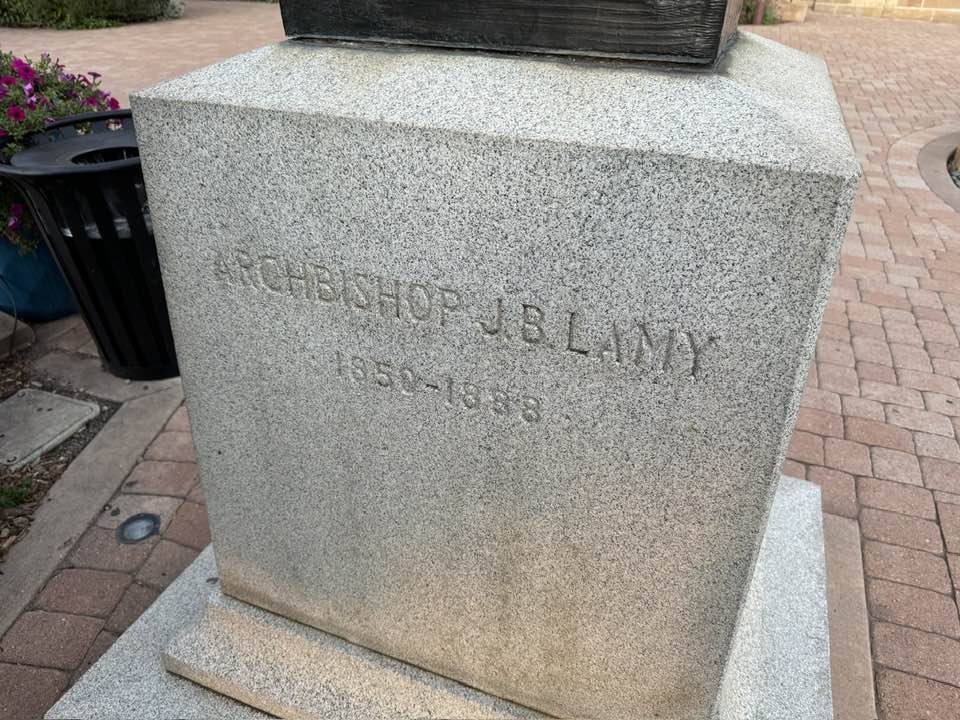

Cather based her character Jean Latour on the life of Jean Baptiste Lamy, who, like Latour, was vicar apostolic of New Mexico and then the first archbishop of Santa Fe from 1875-1885. I read the book in the early eighties and again perhaps 15 years ago, for an adult education class I organized at St John Chrysostom Church in Rancho Santa Margarita.

Along my holiday road this week, it came alive as it never had before. I listened to Cather’s account of Bishop Jean and his friend Eusebio, a Navajo chief, setting out for Santa Fe from the Navajo reservation, a journey by mule of 400 miles, while I was covering the same ground in the mighty Honda on I-40. Cather’s description of life in the Pueblo of Acoma deepened my sense of wonder when I visited the old Acoma mesa myself, continually occupied for nearly a thousand years.

Needless to say, I galloped into Santa Fe with an heroic view of Cather and her episcopal character. Yet a cathedral docent took a different view when I visited the next morning. They greeted me warmly and explained that Archbishop Lamy, a French missionary, had naturally chosen the midi Romanesque style when he rebuilt the church. I replied that I was recently steeped in Cather and asked if it happened that the actual archbishop had found the sandstone himself and fallen in love with it. Their smile faded. I got the feeling I get when I realize I’ve offended someone. They said they’d read the book some years ago but stressed that it was pure fiction. They said Cather had only spent five or six months in Santa Fe. They couldn’t confirm the story about the sandstone.

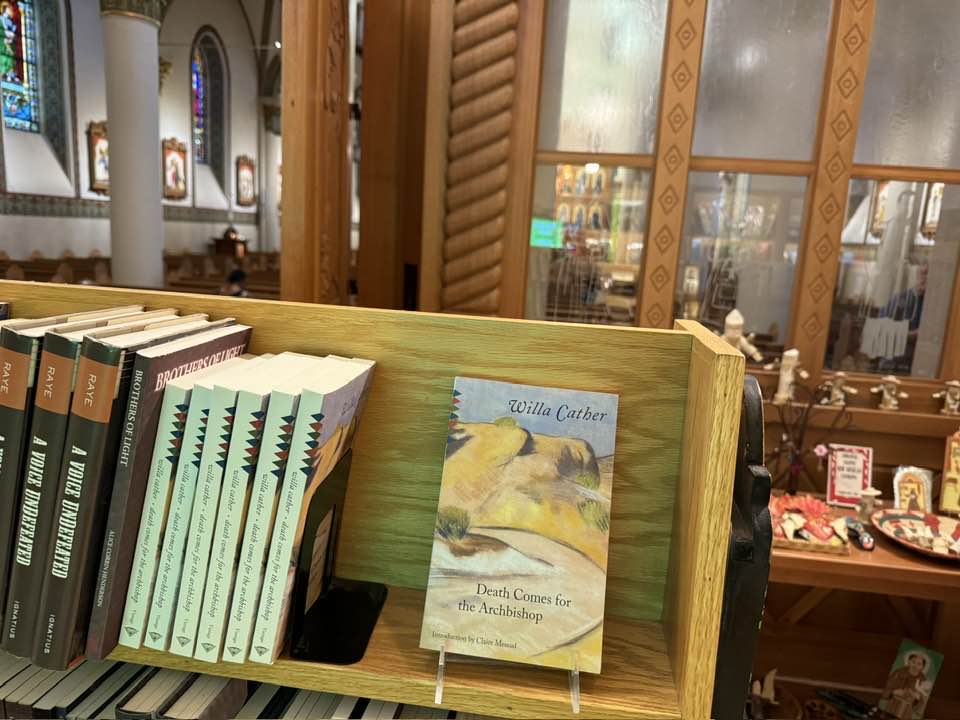

There’s no accounting for taste, of course. And the docent was right to say the novel is fiction. But the Cather question must come up pretty often. She might not deserve her own chapel, but a Cather corner wouldn’t be out of bounds. Given the savage abuses of some of the Franciscans in Spanish colonial times, the pious, compassionate ministry of Bishop Jean and Fr. Joseph, albeit fictionalized, couldn’t possibly put a kinder face on the Roman Catholic Church’s mid-19th century mission work in the New Mexico and Arizona territories. The book also glows with Cather’s deep Catholic faith. I’d tell visitors that her work should be taken as fiction, scrupulously compared with historical sources, and admired as a timeless gift of love to the church and heart of Jesus Christ.

The good news is that Cather’s book is on sale at the cathedral bookshop. So was the current edition of a guidebook, first published in 1947, which discloses that the cathedral’s golden brown sandstone came from atop a mesa in a town now called Lamy, named for the real archbishop, located 18 miles south of Santa Fe — a long afternoon’s mule ride. I was tempted to follow in Jean and Joseph’s steps. Instead, I followed in Kathy’s steps several years ago and headed north to Chimayo, which Cather also mentions, to scoop up some holy dirt. So I’ve got that going for me. Which is nice.