Notwithstanding the careful work of Cold War-era diplomats, history has not yet decided for all time if the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan are two Chinas or one.

But there is definitely just one tropics. When my Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles colleagues Fennie Hsin-Fen Chang, Katherine Feng, Thomas Ni, and I stepped into the Kaohsiung (say “gao shung”) sunshine Wednesday morning after a high-speed train ride from Taipei, I remembered my long-ago visit to a city across the Taiwan Strait in mainland China called Xiamen (“shah men”). It was 1985, when I was adjutant to former President Nixon. Xiamen has the same bright, clear sun as Kaohsiung — low nineties, high humidity, like Miami in late summer.

Traveling the world and meeting with leaders were among 37’s sources of both recreation and, he hoped, redemption. China’s rulers flew us south from Beijing (on a private 727; those were the days) because they wanted 37 to learn about ambitious plans for the region’s economic development. The night we arrived, Xiamen’s Communist Party boss hosted a dinner in Nixon’s honor that featured several rounds of toasts with Maotai, a high octane liquor that had sustained China’s communist revolutionaries during the Long March.

Traveling the world and meeting with leaders were among 37’s sources of both recreation and, he hoped, redemption. China’s rulers flew us south from Beijing (on a private 727; those were the days) because they wanted 37 to learn about ambitious plans for the region’s economic development. The night we arrived, Xiamen’s Communist Party boss hosted a dinner in Nixon’s honor that featured several rounds of toasts with Maotai, a high octane liquor that had sustained China’s communist revolutionaries during the Long March.

Earlier in this visit, Nixon’s security aide and I had lunch in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People with Deng Xiaopeng’s assistants, one of whom challenged Nixon’s bodyguard to a Maotai duel. In Xiamen, I remember the three of us giggling a little in the hotel elevator as we rode upstairs to our rooms after the banquet. It was the only time in 15 years I saw Nixon even slightly overserved. I hasten to add it was also one of my few such experiences. The lesson is to be respectful of Maotai.

In our defense, we had been toasting world peace and the friendly relations between China and the United States that Nixon had forged 13 years before with his historic visit to Beijing. Nixon’s partner Henry Kissinger, jokingly giving Maotai partial credit, had, with the Shanghai Communique, launched a half-century of what’s called strategic ambiguity. Taiwan could go its way economically and to an extent politically as long as no one messed with mainland China’s insistence that someday the island nation will become part of the behemoth nation.

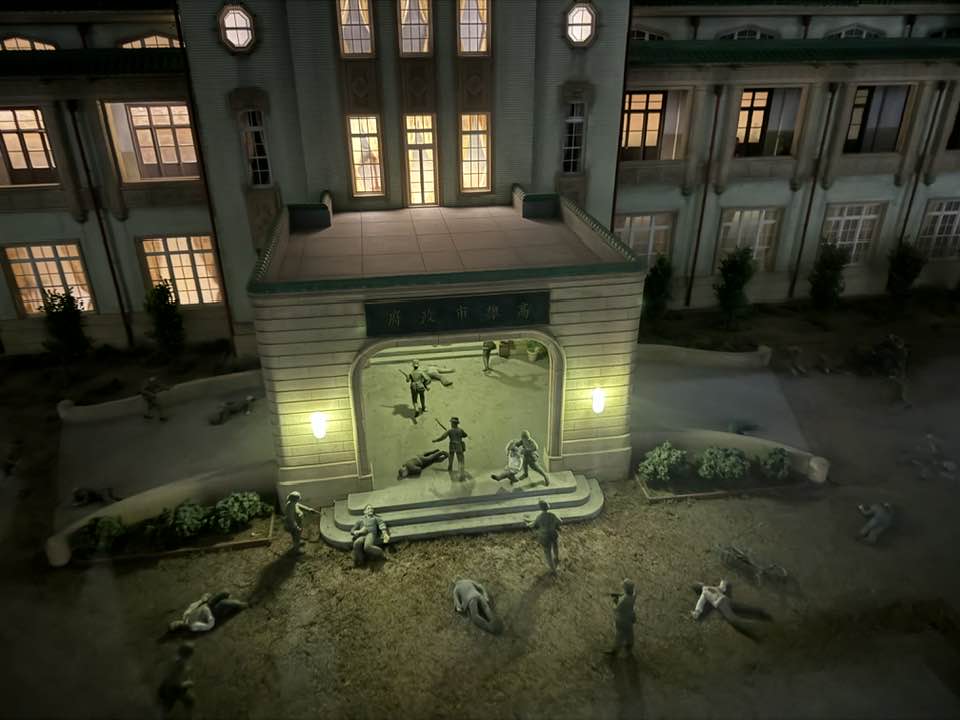

In the mid-eighties, the diplomatic skies were still Kaohsuing- and Xiamen-clear, with a 100% chance of more mutually profitable joint business ventures. Taiwan Strait skies are now threatening. The ignoramus Trump, insecure PRC strongman Xi Jingping, and pro-independence Taiwanese have all done their part to clog the well-lubricated gears of strategic ambiguity. The chances of conflict are said to be higher than anytime since Nixon’s historic visit. One hears, from well-connected Episcopal Church sources no less, that the Pentagon thinks war may come in 2027. Or war may not. Wars don’t just happen, of course. People start them. One between China and Taiwan could end up being the bloodiest event of the century so far, especially if the U.S. was drawn in. It’s hard to believe anyone wants it.

But China insists it has a red line, and Taiwan dare not cross it. A lively city of 2.7 million, Taiwan’s largest port, Kaohsiung faces the mainland and would be a top military target. Yet geopolitics have come up only tangentially during our visit so far, though when one mentions them, the listener’s eyes and nods instantly register awareness. But nobody wants to say much. Nearly three-quarters of Taiwan’s people express trust in their government. Loose, careless talk wouldn’t help. So folks are keeping calm and carrying on.

During a dinner meeting with priests from southern Taiwan, politics only came up when two rectors mentioned losing congregants after the government turned military housing into affording housing. And good for the government. Socially progressive, democratic, prosperous, and innovative, rich with history and in spirituality, Taiwan’s the greatest country in the world recognized by the fewest number of other countries. Most of the world is caught in the gravity of China’s growing power and wealth.

This week, we are feeling the pull of Taiwan’s love. Among its Episcopalians the last four days, we’ve never felt more welcomed. On Thursday morning at St. Timothy’s in Kaohsiung, we hung out for three hours with 30 seniors at their weekly fellowship, exercise, and lunch meeting. Three undergraduates from a nearby university helped out, including by offering blood pressure checks. Though many of the participants in this government-supported program weren’t church members or Christians, our host, St. Timothy’s priest-in-charge the Rev. Stoney Chia-Kuei Wu, reflected for a few moments on Christ the good shepherd. Everyone joined in the songs.

This week, we are feeling the pull of Taiwan’s love. Among its Episcopalians the last four days, we’ve never felt more welcomed. On Thursday morning at St. Timothy’s in Kaohsiung, we hung out for three hours with 30 seniors at their weekly fellowship, exercise, and lunch meeting. Three undergraduates from a nearby university helped out, including by offering blood pressure checks. Though many of the participants in this government-supported program weren’t church members or Christians, our host, St. Timothy’s priest-in-charge the Rev. Stoney Chia-Kuei Wu, reflected for a few moments on Christ the good shepherd. Everyone joined in the songs.

Stoney’s spouse, Wendy, sat with us at lunch. We talked about the joys and challenges of raising her children, fourth grader Phoebe and fast car-loving Timothy, turning five this month. Timothy is one of the 200 preschoolers and kindergarteners at nearby St. Paul’s Church, which we toured with its vicar, the Rev. Deledda Tsai, wandering among the neat lines of backpacks, helmets, and shoes, waving and bumping fists. Rev. Tsai picked us each a fig from a tree out front.

When the St. Timothy’s seniors spotted one of their own — I will be in the market for a ministry like this before too long — they invited me to join in at ping pong toss and a pinball game using handmade cardboard machines. One member, Christy, who bubbled with joy and presented herself as the de facto organizer, disclosed that just five years ago, she was in the depths of depression. We gave thanks for her healing. The gracious senior warden’s father, who founded St. Timothy’s, is near death. Warden Jane’s two sisters have arrived from abroad to help keep watch. I anointed his spouse, who had come to spend the morning with her friends.

All of this extended family stuff should sound familiar to church people. As sometimes also happens, a few conversations were edgier. Over the course of a day and a half, my colleagues and I had some chats with Dr. Danny Ho, a retired child psychiatrist. He believes Taiwan’s people should stop moving to the U.S., where they are coming to fear gun violence and racism, and stay home to keep China strong. As we compared family pictures, Danny and I agreed that war the worst sin — war in Israel and Palestine, Tony said, and, we of course meant, the future war that may not be over Taiwan.

It quickens one’s prayers for peace to have personal experience of a gracious land, making friends among its people, participating just for a moment in the peaceful courses of their lives, while knowing that in a nearby capital, plans are being drawn for aggression and conquest that would turn every tender, everyday scene into catastrophe. Whether all of Taiwan’s precious, inalienable birthrights, especially peace, justice, and freedom, will continue to coexist is up to powerful people in three capitals, summoning all the prudence, firmness, and humanity they can. So send down the Holy Spirit upon them, mighty God, or let’s get out the Maotai — whatever works.