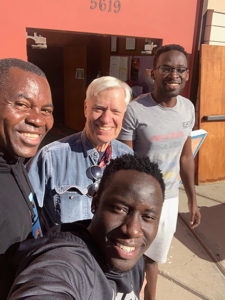

Clarke Prescott, center, poses with three clients of Casa de Caridad at All Saints Church, Highland Park.

On a recent morning, Johnson, Musa and Hakim were helping to hang new doors at their home—at All Saints Episcopal Church in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles.

There, they share the kitchen and facilities, a television, and sleep in the choir loft, as residents of Casa de Caridad (Home of the Heart), lovingly dubbed Casa de Clarke, a homeless shelter started by All Saints’ priest-in-charge, the Rev. Clarke Prescott.

“Currently we have eight people in the shelter; five men; thee women. All but one are refugees seeking asylum,” Prescott told The Episcopal News. “Most are young. Most are educated, with college degrees. They’re good folks that just have been caught in tough circumstances.”

Resisting oppression; forced to flee

Civil war forced Johnson, 50, a former high school geography teacher, to flee the Central African nation of Cameroon. He left behind five children, aged 2 to 27, his wife and extended family members.

“Villages were being burned down and people killed,” Johnson (whose last name was withheld for his protection) told The News recently. “I lost many of my colleagues.”

He, along with other teachers, trade unionists and professionals joined nonviolent demonstrations to protest government efforts to impose the French language upon English-speaking regions of the country. The government response was swift and brutal, pitching the country into civil war.

“When they started chasing us, I went to Eastern Europe, studied for a master’s degree in community development and urban planning, assuming that the protests would be over when I finished,” Johnson said.

“I thought the government would be looking for lasting solutions to bring an end to the protests. Instead, they went from protests to full-fledged war.”

Aware that returning to Cameroon would place him in danger, he applied for an educational program in Los Angeles. He is hoping, with the aid of Casa de Caridad and the Los Angeles Program for Torture Victims (PTV), to gain asylum.

For Hakim, 28, it is a familiar story. A grassroots activist in Uganda, he worked as a counselor helping to inspire and resettle children living on the streets.

“We had an idea to bring artists, people who have made it from our country, to inspire the kids, to show them that, though you might be street kids, you can make it,” he told The News.

The group hosted popular artist Robert Kyagulanyi, also known as Bobi Wine, whose pop music lyrics were frequently critical of the authorities and who reportedly was considering running for president of the country. The effort sparked a government crackdown on artists.

Afterwards, “people who helped with the campaign were abducted,” said Hakim. “They were accused of trying to help take over the government through our organization.”

He fled, eventually arriving in Los Angeles along with his cousin Musa. Through PTV they Casa de Caridad, where they have been living since July.

“We came here and Father [Prescott] was really good to us,” said Hakim. “Since that day to today is a very great change. We are seeking asylum.”

Initially, they felt overwhelmed by bureaucratic red tape. “We don’t know what to do about filing cases and dealing with the system. We were feeling very stranded, very insecure with community.”

Eventually, they learned about PTV. “By then, we were sleeping in our car,” he recalled. “We were going to try and look for a place to stay. But, unfortunately, we couldn’t get one.”

Little organizations, mighty missions

PTV “is a little organization with a mighty mission, not unlike Casa de Caridad,” according to clinical director Carol Gomez. The nonprofit program was founded nearly 40 years ago by two asylum seekers who fled to the U.S. from Argentina and Chile for their own lives, she said.

“Fr. Clarke and Casa de Caridad have truly been a Godsend to us in times of crisis,” Gomez said. “They have kept some of our people from sleeping in their cars or on the street, as they await their asylum cases and for their work permits to come through.”

PTV “provides refugee survivors with a safety net of trauma-specialized case management, psychological healing and care, medical care, legal forensic evaluations and expert witness testimony in immigration court.”

Additionally, weekly gatherings help promote resilience, creativity and sow seeds to reconnect with trust, break from isolation and find hope and strength to move forward, Gomez told The News.

“We support refugees who are asylum-seekers from more than 70 countries who have reach the U.S. after escaping state-sponsored torture or persecution as a result of their political opinion or membership in a targeted social group of tribe, ethnicity, religion, gender or sexual orientation,” she wrote in a recent email. “Most arrive severely traumatized, with psychological and physical wounds, and with little more than the shirts on their backs.”

She added: “Within two days of [PTV] connecting with Fr. Clarke, an immigrant mom and two kids called PTV in crisis as they were dealing with a multitude of critical health situations for one of the children, and were living in their car. Fr. Clarke welcomed them into Casa de Caridad with open arms.”

Responding to community needs

Casa de Caridad began with a phone call about four years ago, recalled Prescott, who retired in 2005 as rector of All Saints Episcopal Church in Riverside. Although he had moved away from the Southland, a call to serve eventually brought him back. He served at churches in Menifee and Lake Elsinore in the Diocese of San Diego.

In 2014, he was invited to serve as priest-in-charge at All Saints, Highland Park. The scrappy congregation has maintained its mission-mindedness, with an average Sunday attendance of about a hundred. An English-speaking service congregation typically numbers about 35 and a Spanish-language service has as many as 60, depending on the occasion, Prescott said.

It was an especially active El Niño winter season when a local nonprofit agency contacted Prescott to see if the church would be willing to help shelter homeless people from the heavy rains.

Instinctively, “I said yes,” Prescott recalled.

The seasonal shelter opened that first year, and “the second year we did a winter shelter, and housed 35 to 50 people from December to February,” Prescott told The Episcopal News.

“We did not do that this past winter. We did a smaller year-round shelter for 10 people.”

The shelter is self-funded and self-supervised; typically, residents stay six months. A resident advisor, also a member of the program, opens the doors each evening. Roles and chores are decided by the members.

“There is no paid staff. We have a supervisor who helps. Residents are allowed to stay from 6 p.m. to 8 a.m., seven days a week,” Prescott said. “On Sundays, they make sure the church is clean and ready for worship.

They cook, clean, and maintain their living space. Women live in a separate residence, a small house on the church property. Although most are refugees; at times residents include the local homeless population, Prescott said.

Working with PTV, residents receive legal, medical and other assistance in seeking asylum. The goal is to help them get green cards and find work and stable housing. Prescott puts them to work as well, with routine chores and even hanging church doors.

The irony is not lost on Hakim. “In my lifetime, I have never lived in a church. I am a Muslim,” the 28-year-old told The News. “I’m glad to tell you that this has been amazing and very peaceful, very beautiful.

“On Sundays, of course, we leave the church. We make sure it’s clean so others can use it.

“It feels good to live here, especially from where we were before. We were stranded, we had nowhere to live. We didn’t know if we would eat.”

Seeing others come and go, aided in finding housing, fills him with hope.

“My cousin and I have an appointment next month with immigration,” he said. “With this, we applied for working permits so we could work and then find a place to stay. I am planning to go back to school.”

Often, he goes with Prescott to pick up donations from food banks and distribute them to the local homeless. Of Prescott, he says: “He is our father. He’s a great guy.”

Johnson agreed that Casa de Caridad is a bright spot in otherwise difficult circumstances for him. He hopes to be reunited with his wife and children someday and to move them from Cameroon to Los Angeles.

“I must assure you that there is nothing in life, nothing in life more difficult, than each time my daughter asks my wife when I am coming,” he said, his voice tinged with sadness.

“She is seven. Her name is Peace. She does not understand why she cannot see me anymore. She does not know what is happening.”

He said, “I am praying to God. Praying for the American government to grant me asylum. If, in due course it gives me asylum, I think of nothing but my children.

“I have no relation here who can house me and [because of legal status] am not able to work. It is not a very easy living. Sometimes, I have to be visiting parks, and moving around or looking for a place to sit down.”

Casa de Caridad and PTV, he said, “have done a great job for me. I am somebody who is always grateful for life. This is a wonderful initiative. We have food. We have heat. We have electricity.”

Prescott said the causes of homelessness are complicated and varied, endless.

“Whether someone got sick, whether they lost their job, their rent was increased, they had a fight with their parents, or divorce, the reasons for it are just endless and, because of that, there is no one response that’s going to work.

“It’s been a longtime challenge for Los Angeles for over 30 years,” he continued. “There is not enough low-income housing. As rents go up, people are unable to afford them. If they have a choice, whether to eat or put a roof over their head, most people decide to eat.”

“People can’t afford to live in L.A. anymore. Houses in my neighborhood are a million dollars. My whole congregation together couldn’t buy a house.”