Arthur and Peggy Littleworth are pictured in their Riverside home in 2010. Photo: Gabriel L. Acosta/UCR Magazine

Arthur Littleworth’s amazing life has inspired both a film and a book, but the 98-year-old retired Riverside attorney and lifelong Episcopalian considers his extraordinary leadership simply to be what faith, civic responsibility and the times in which he lived and the community he loves needed of him.

In 2020, the City of Riverside produced a two-hour documentary film, A Good Life, about Littleworth’s contributions, and proclaimed him its “citizen of the century.” The film chronicles Littleworth’s exceptional accomplishments through the eyes of those who know and worked alongside him to make Riverside public schools the first to integrate in the nation without a court order; to save the iconic Mission Inn, the largest mission revival style building in the United States; and to ensure quality regional drinking water.

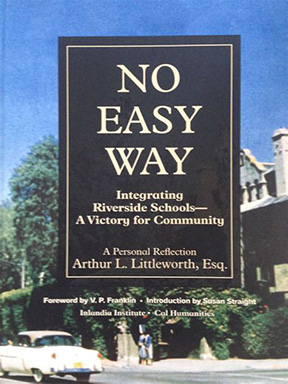

Six years earlier, Littleworth had written a memoir, No Easy Way, borrowing the title from a column about him by Tom Wicker of The New York Times. Wicker described the challenges Littleworth faced as school board president when on Sept. 7, 1965, a month after the Los Angeles Watts riots, an arsonist firebombed Riverside’s segregated Lowell Elementary School.

No arrests were made; the attack prompted boycotts by Black students and amplified already-heightened racial tensions so much it forced Littleworth’s family to relocate because of threats of violence, his daughter, Anne Taylor, recalled in the film.

Littleworth’s memoir, “No Easy Way,” describes the difficult, but successful effort to integrate Riverside’s racially segregated schools in the 1960s.

Awakening one morning, she looked out, “and there was a cross on our lawn,” Taylor said. “And I quickly went in and told my parents, and it was after that time that we went to another home where there was security.”

Littleworth called the attack the beginning of “the week from hell,” but by the week’s end, the school board had pledged to have an integration plan within 30 days.

“I had concluded in the first days after the fire that the crisis would get worse if nothing were done, and if we were going to do anything constructive, we had better do it at once,” Littleworth wrote. “To ‘study’ the situation would have been a disaster. To minority groups, the word study is a euphemism for not doing anything. Delay was not going to teach us anything new,” he added in the memoir, which he dedicated to the parents, the school board, educators and individuals “who stretched their vision to see the future and become a small part of the history of the United States.”

A timeline was quickly established, and Lowell students were redirected to other schools with low minority pupil enrollment. “We did what the Board thought was right,” Littleworth concluded. “Within a week we decided that all three segregated schools, Irving, Lowell, and Casa Blanca, should be integrated and … within approximately 30 days, we had a plan for complete integration – a pragmatic plan without developing a deep split in the Riverside community and thereby avoiding a violent confrontation. “

The effort brought him to the realization of “how left out the minority community felt. They didn’t believe anything we said,” he wrote.

“We had to show people that they could have faith and trust in the leaders of the community,” he recalled. “So, we just listened, and then we tried to do what we could about the righteous complaints. To the parents, this was an education problem, but it really was a Riverside community problem – the problem of trying to be one people, one community. For a generation or two, we had some success, but times do change.”

A life of faith and service

The son of British immigrants who met on a boat trip to Canada, married and later moved to California, Littleworth grew up at Grace Episcopal Church in Los Angeles (later demolished to make way for the 110 Freeway). There he met his first wife, Evelyn Low, and the Rev. Douglas Stuart, a priest and mentor whose friendship had a lasting influence.

“Every Sunday at Sunday School the rector read from the Offices of Instruction of the [1928] Book of Common Prayer, and we responded appropriately,” Littleworth told The Episcopal News. “The Ten Commandments are summed up in these two commandments: Thou shalt love the Lord thy God, and thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” This was the core of my religion. It still is, and has guided all the affairs of my life.

“I considered becoming a priest, but I did not have the calling,” Littleworth wrote in response to questions emailed to him by The News. He survived a disabling stroke in 2008 that left him with limited speech.

Excelling early in life as a leader, Littleworth was president of his 1941 Washington High School graduating class and won a Pacific Coast Regional Scholarship to Yale University. There he earned a bachelor’s degree with honors in history and won the Andrew White Prize in History for the best essay in English, European or nonwestern history.

But he received his degree by mail, having enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He served from 1944 to 1946 in the South Pacific aboard the USS Currituck, part of the fleet that accepted the surrender from Japan in Korea and China.

After the war, he and Low married at Grace Church on Sept. 20, 1947, the same year he earned a master’s degree in American History from Stanford University. He graduated from Yale University Law School in 1950, winning the Francis Wayland Prize, awarded to the student showing the greatest proficiency in preparing and presenting a case in negotiation, arbitration, and litigation.

That same year, he became a member of All Saints Episcopal Church, Riverside and joined the Best, Best and Krieger law firm because he believed the Inland Empire city to be a good place to raise a family and serve his community.

The Mission Inn, a distinctive cultural and architectural gem in Riverside, is still intact partly because of Arthur Littleworth’s determination to save it from ruin.

Appointed to the school board in 1958, he served until 1972, including 10 years as president. In 1976, Littleworth was appointed the first president of the Mission Inn Foundation, a group of Riverside citizens charged with the operation and restoration of the Inn. Working with the Riverside Redevelopment Agency, the city acquired the inn, which was in bankruptcy and disrepair. A year later, it was designated a national historic landmark. Eventually the city sold the hotel to a development firm, which began a seven-year $50-million renovation project. In 1992, the inn was purchased by a local owner and successfully reopened.

Littleworth’s stellar career as an environmental and water attorney is well-documented. In 1977-78, California’s then-Governor Jerry Brown appointed him to Brown’s Commission to Review Water Rights Law. Littleworth’s clients included the State Water Contractors (serving 20 million people); East Bay Municipal Utility District (serving Oakland, Berkeley, the East Bay); Riverside, Pasadena, Ventura, the Long Beach Desert Water Agency; the Metropolitan Water District; and the Irving Company.

He represented the City of Riverside and most of the Riverside area pumpers (about 4,000) in contentious litigation among San Bernardino, Riverside, and Orange Counties over the waters of the Santa Ana River. The litigation, settled in 1969, assured Riverside’s historic water rights. The wells are the city’s principal water supply source.

As Best, Best and Krieger law partner Eric Garner said in the 2020 film: “The lasting legacy of Art Littleworth and water is that when you wake up in the morning, and you turn on the tap, you don’t have to think about where the water comes from.” Garner and Littleworth also published three editions of California Water, a definitive resource for water education in universities and for water rights attorneys.

In 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court appointed Littleworth a Special Master to decide a case between the State of Kansas and the State of Colorado involving the water rights to the Arkansas River, nearly a century’s-old dispute. The case lasted 17 years and was tried in five phases, with the court confirming Littleworth’s decisions in each phase. The case established legal precedents, particularly financial damages for shortages in interstate river flow.

Attorney David W. Robbins, who represented the state of Colorado in that proceeding, recalled in the film that Littleworth “encouraged my opponent, Mr. John Draper, and me to treat one another collegially. In part the result of that, Draper, who was the attorney for the state of Kansas, and I have, over the years, become friends. [Littleworth] is the most amazing gentleman, a calm but commanding presence.”

That same year – 1987 – Littleworth established an endowed scholarship for students attending UC-Riverside, an act of generosity that changed the lives of students like Bailey Powell and Austin Claiborne, who also appeared in the film.

“The scholarship truly changed my life,” Powell said. “It’s changed me as a person. Truthfully, I don’t think I would push myself as hard. For me, this scholarship was a support system … for four years it was me telling Arthur and [his second wife] Peggy about the things I was doing … and I was always met with incredible support and excitement. And it just made me want to push more and more.”

Claiborne, program coordinator for the NBA’s Golden State Warriors Foundation, said the scholarship not only offered financial support but also afforded him confidence, the passion to pursue his dreams and the inspiration to pay it forward.

“If there’s any way that I can make an impact or say thank you, it’s trying to recreate that in my own self, trying to help as many people as I can,” Claiborne said in a film interview. “Sometimes, they just need a mentor like Mr. Littleworth, who inspires them to be able to realize that their dreams are possible … if you’re able to do that, I think it’s huge.”

La Sierra University presents an honorary Doctor of Law degree to Arthur Littleworth in 2017.

In 1994, 10 years after the death of his first wife, Littleworth married Peggy O’Neill Shaw, who has become his caregiver since the stroke paralyzed his right arm and side. Since the stroke, he performed many hours of physical therapy – regaining the ability to walk with a cane and limited speech – and began painting with acrylics. Left-handed, he was able to continue to communicate by writing on yellow legal pads.

Friends like Jane Carney recall Littleworth’s penchant for international travel, for parties and celebrations, and a light-heartedness that, at times, seemed incongruent with the local, regional and nationally recognized attorney and civic activist. In 2017 he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from La Sierra University and, until recently, continued to advise colleagues about legal matters.

“Here is this very dignified man, the very image of what you think of as a community leader, a senior attorney, involved in an important law firm – and he is so much fun. He loves to dress up in costumes,” Carney laughs heartily as she remembers some of the parties. “He’s also a wonderful photographer, and a rabid Rams fan. He just loves to have fun.”

Littleworth often dressed as Santa Claus at Christmas and drew inspiration for Halloween costumes from NBC’s Saturday Night Live Coneheads skits, and from the Blue Man Group, Harry Potter’s Dumbledore, as well as pirates, monks, even a Scottish Highland warrior.

Now, facing another daunting challenge – advanced kidney disease – Littleworth remains faith-filled.

Says Carney: “He’s a man of really outstanding character. I assume that a large part of that comes from his faith. He is consistently just what you would call a virtuous man.”

All Saints’ rector, the Rev. Canon Kelli Grace Kurtz, agrees. “His faith has taught him that all are beloved of God, and that truth has influenced and guided his life, his vocation, his ability to love his neighbor. Nothing short of treating the other as a child of God worthy of dignity and grace can satisfy Mr. Littleworth’s efforts. He is a witness for the Good News and All Saints is a better faith community for his witness.”