Hearing loss is tough for a music lover. For all I know, loud music was the culprit. I hear worse with my left ear, which was closer to the “Thunder Road” coming from driver’s side speakers all those years. I could’ve turned it down, of course, but it always sounded better loud.

I’m paying the price. In recent years, even familiar songs deconstruct themselves in my weakening ears. I hear the sound but often can’t quite catch the key. Imagine the beautiful harmonized “ah” at the beginning of “Don’t Worry Baby” without the harmony, just a blur of atonality. I’ve chosen to blame compressed digital audio files for not sending enough information to my brain. It’s easier than blaming my brain.

A magic “music” option for my hearing aids helps some. Even better is live music, which comes through clearer than recordings. For the last year or so, on a half-dozen Thursday evenings, I’ve purchased a really good seat at the LA Phil. The time is now. Music may keep getting fainter and more indecipherable, plus I won’t always work six minutes from the Disney Concert Hall.

Tonight was a program guest conducted by Rafael Payere, the dynamic music director of the San Diego Symphony Orchestra, featuring Brahms’ First Symphony. Payere didn’t use a score, which conductors often don’t with warhorse pieces like this one. It opens with a wall of sound Brian Wilson would love, probably does, which, familiar as it is, was hard for me to make out at first. After I made a few technical adjustments on my iPhone, which talks to my hearing aids, it settled in.

Tonight was a program guest conducted by Rafael Payere, the dynamic music director of the San Diego Symphony Orchestra, featuring Brahms’ First Symphony. Payere didn’t use a score, which conductors often don’t with warhorse pieces like this one. It opens with a wall of sound Brian Wilson would love, probably does, which, familiar as it is, was hard for me to make out at first. After I made a few technical adjustments on my iPhone, which talks to my hearing aids, it settled in.

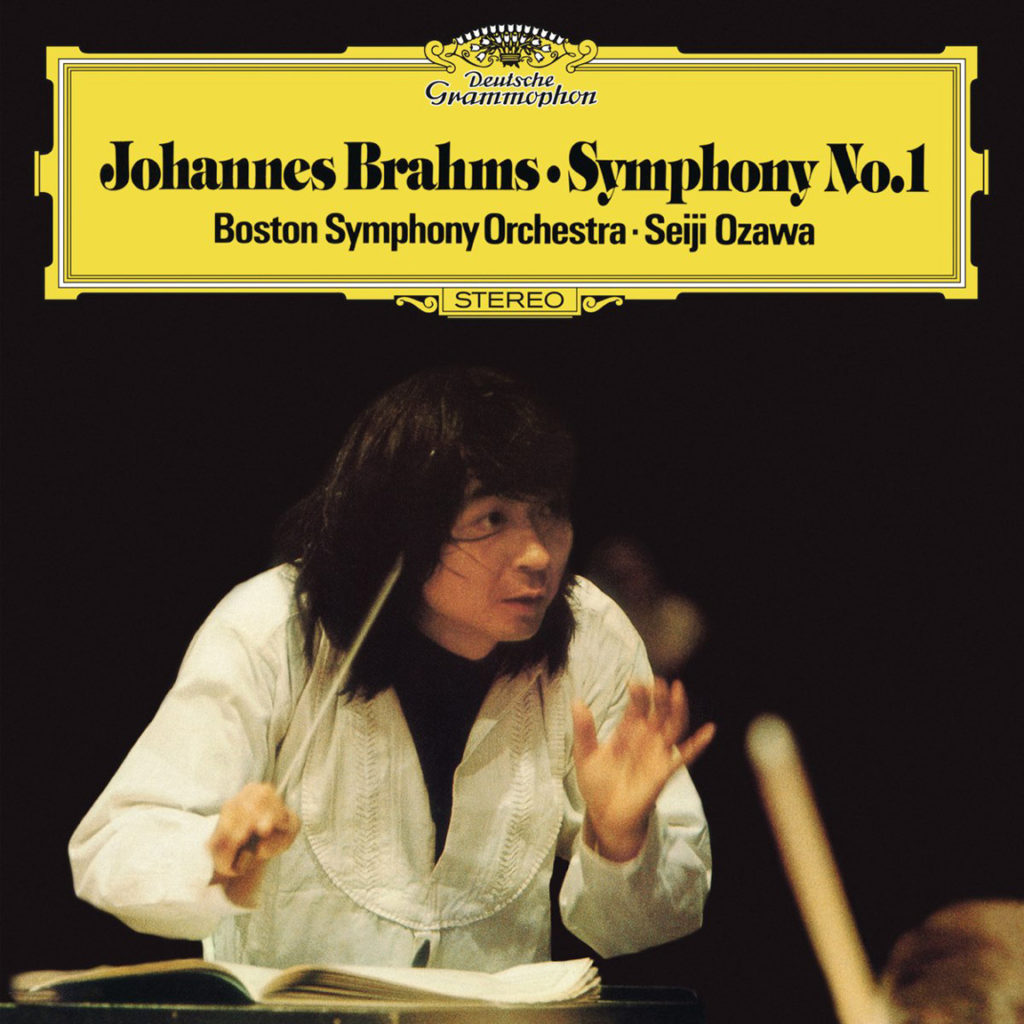

I’ve loved this music since the late seventies, when I bought and basically memorized Seiji Ozawa’s recording with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. I’d never heard it live until tonight, and it occurred to me I might not again. I was on the edge of my seat for 45 minutes.

Said to have been intimidated by Beethoven’s Ninth, Brahms waited until middle age to finish it. If you don’t know it, it’s a musical ten-layer fudge cake, with dozens of themes and hooks to look forward to. A brass fanfare in the fourth movement, first quiet, later thrillingly loud, as though the gates of heaven are opening. In the second movement, a simple melody, ascending and descending, also offered twice, first by woodwinds, then taken by the concertmaster’s violin and a French horn while the orchestra thumps triplets underneath.

Beethoven had his “Ode To Joy” in the fourth movement of the Ninth. Brahms matched it with a sturdy folk tune played by the strings in the fourth of his First that, a century later, the Kingston Trio borrowed for their Christmas album. When I hear it, I can’t help hearing them singing: “The white snows of Christmas/Fall into the quiet town…”

Beethoven had his “Ode To Joy” in the fourth movement of the Ninth. Brahms matched it with a sturdy folk tune played by the strings in the fourth of his First that, a century later, the Kingston Trio borrowed for their Christmas album. When I hear it, I can’t help hearing them singing: “The white snows of Christmas/Fall into the quiet town…”

I was a half-hour late tonight because of a family errand and so was not eligible to be seated until intermission. I’d come for the Brahms, which was last, so I wouldn’t have minded waiting. But four ushers collaborated to enable me to sit in an odd little room that can only have been made possible by Frank Gehry’s architecture and where I could watch the second selection, a Wagner vocal suite, on CCTV while hearing the music waft up from the auditorium. They didn’t have to. They just did. Such kindness in Eastertide, like the music we love, makes the heart sing.