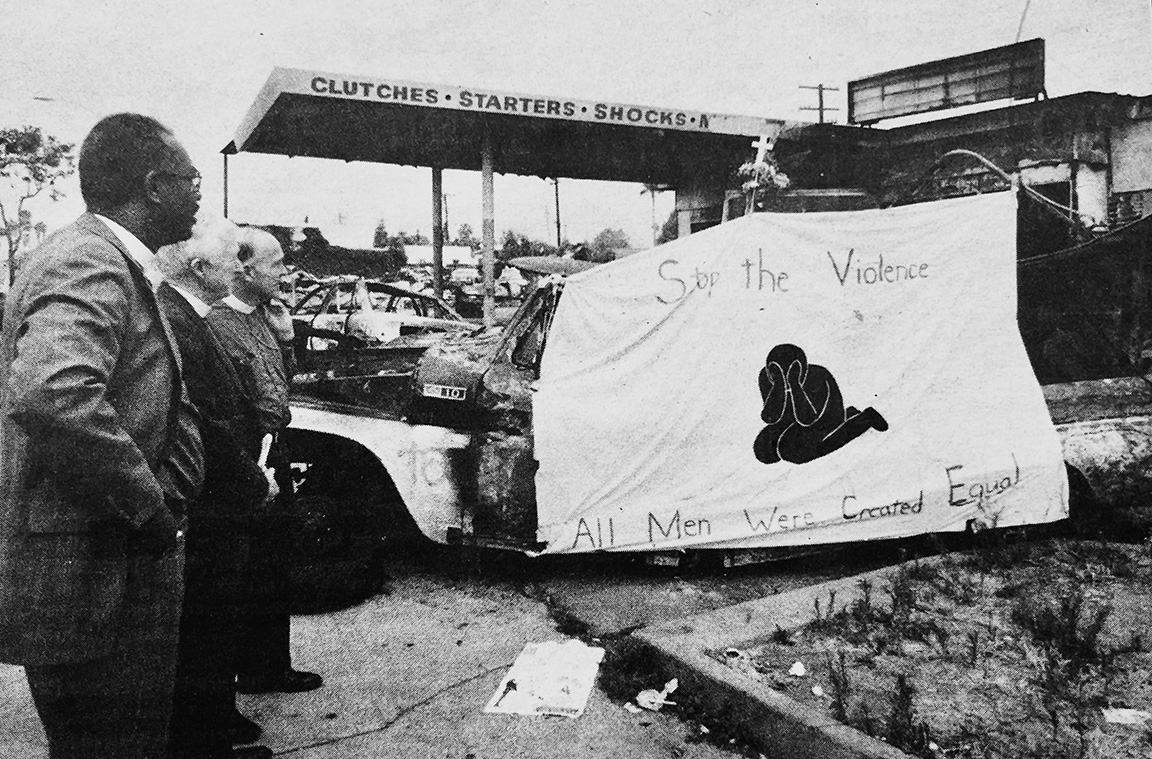

Surveying sign affixed to burned truck at L.A. intersection of Florence and Normandie in wake of 1992 uprising are (from left) Bishop Suffragan Chester Talton, Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Edmond Browning, and Bishop Diocesan Frederick Borsch. (Episcopal News photo by Al Bender)

[The Episcopal News] Spared destruction in the city’s worst rioting, churches in the Los Angeles Diocese mobilized quickly to offer physical and emotional support to a dozen congregations most deeply affected by the violence.

Bishop Frederick Borsch announced on the morning after the initial eruption that eight (later nine) churches would be eligible for $4,000 grants.

It was later decided that the money – to come from Borsch’s own discretionary fund and a $25,000 emergency grant from the Presiding Bishop’s Fund for World Relief – would be dispersed to rectors of churches with largely black and Korean congregations for the human needs of their members.

During the scramble to mount relief efforts, the steadily expanding violence forced closure of Diocesan House’s West Fourth Street building on April 30.

Staff worked out of the Christian Education offices at St. James, South Pasadena, through the weekend, coordinating offers of help from various churches in collecting food, clothing and money.

By Sunday, food was piled high on the lawn of All Saints, Pasadena, where the Rev. Jesse Jackson preached. St. Augustine’s Church, Santa Monica, collected $2,553.30 which the Rev. Fred Fenton turned over to the First African Methodist Episcopal Church in South Central Los Angeles.

Three of the dozen Los Angeles churches eligible for the bishop’s relief set up food and closing drop off centers.

On May 6, Presiding Bishop Edmond L. Browning brought promised of support and additional aid from The Episcopal Church.

But mobilizing the physical aid, for many, was the easy part.

More difficult was the struggle to deal with the horror and comprehend the genesis of the forces that sparked eruption of the violence.

“It may be that the most important thing that we can do now is to come together and pray,” Borsch told 300 clergy and lay leaders who gathered on May 3 at St. James Church, Los Angeles, while fires still smoldered and National Guard units were posted nearby.

“People are angry and upset, deeply saddened and deeply hurt. Many people I talked with today are in desperate situations,” Borsch said.

Bishop Suffragan Chester Talton said he was at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, along with other religious and city leaders, on the night of April 29 as violence escalated in South Central Los Angeles.

“We were reeling from the verdict,” Talton said of the acquittal in Simi Valley of four police officers accused of beating black motorist Rodney G. King – the event touched off violence.

“All of a sudden there was some way to be involved We went to the church. It was full of people. It was a wonderful and heroic effort to channel emotions from that verdict,” Talton said.

Racism blamed

During the meeting at St. James, several pleaded for an end to racism.

“How can we become one with people we sometimes don’t want in our churches?” Hispanic Missioner Carmen Guerrero asked. “People cannot go forward in a healthy manner unless we acknowledge what happened. Unless we begin to realize what is going on beyond the wall, we’re only kidding ourselves.”

Earlier in the day, Borsch honored a long-standing commitment for a visitation to St. Philip’s Church, Los Angeles. There he stressed the need for resolve in rebuilding the community.

“We must have a vision to change the situation,” Borsch said. “We do have enough resources in this country if we would only share them.”

Many of the parishioners said they had steered clear of the violence but still felt the impact.

“It hasn’t affected me in any way,” said vestryman Arnold Sharp. “But it has caused animosity. I went into a market and the way people looked at me, I was lucky to get out alive.”

Eduardo Bresciani (ordained the next month), who prepared the children for the baptism ceremony, said people in the area, now peppered with burned-out markets, were “afraid to go out of their homes.”

He added, “The kids have been very broken. They have been crying and asking why all this happened.”

He said water was also scarce because tap water coming out of the faucet had turned brown because of heavy use of water to fight fires.

The riot forced cancellation of the diocese’s Los Angeles regional celebration scheduled for St. James, Wilshire. It was reset for May 30.

The following week, Borsch asked each of the congregations to obtain access to a fax line to aid coordination with churches needing assistance.

Healing and hope

Parishioners of churches most affected by the riots returned to St. James Church on May 9 for what was described as a service of healing and hope.

Several speakers from the Korean community called for a new resolve to rebuild lost businesses and foster a new understanding.

“Koreans are seen as rough on the outside, but we are very warm-hearted people,” said Steve Rim, from St. Francis Church, Norwalk.

“This creates problems for those people who are not aware of our backgrounds. We have to think how to heal and recover from this situation,” Kim said.

He called for lending a hand “to those who have difficulties in their lives” and learning “each other’s culture so we can have a better understanding.”

“I do not think this was a senseless striking out,” Talton said of the riots. “I think it was meant to say, ‘Look, pay attention,” to those who have power and benefit from power.”

The message from the poor and minorities, Talton continued, is “We are human and if we cannot live, you will not live comfortably. The police are killing us and we will not suffer alone.”

The bishop said that African Americans and Korean Americans “should not be at odds with one another. What we should do is to come together with Spanish-speaking people… and all who feel themselves oppressed in this society.

“What we should do is to seek the real power that we can amass by realizing that until there is justice for everyone, then there cannot be justice for anyone.

“But make no mistake about it, the African American community is at the bottom and until there is justice at the bottom, everyone is in jeopardy.”

Talton called for a new effort in rebuilding society for the long term.

“There is unfinished business in this country,” Talton said. “But all of you must work together.”

He added, “Those who have been privileged must be prepare to give up what they have enjoyed if they are sincere.”