Ugandan praise dancers from St. Mark’s Church, Van Nuys, perform at the Juneteenth Evensong at St. John’s Cathedral on June 18. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

The sweet sounds of the Episcopal Chorale filled the air, youthful Ugandan praise dancers swayed gracefully, and worshipers called out the names of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, Bishop Edward Mackenzie and others in an ancient African water ceremony honoring the ancestors at the first annual diocesan Juneteenth Jubilation Evensong celebration on June 18.

Canon Chas Cheatham leads the congregation and the Episcopal Chorale in “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” sometimes called the Black national anthem. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

About 75 worshippers were greeted by the cathedral co-dean, the Very Rev. Mark Kowalewski before Canon Suzanne Edwards Acton, co-chair of the diocesan Program Group on Black Ministries, and Casey Jones, vice president of the H. Belfield Hannibal Chapter of the Union of Black Episcopalians welcomed them to the 4 p.m. inaugural gathering of Juneteenth Jubilation.

A gallery of photos from the Evensong is here.

Bishop John Harvey Taylor presided over the event, recalling in opening remarks that even after the June 19, 1865, origins of the celebration, when Gen. Gordon Granger made his historic announcement of emancipation for slaves in Galveston, Texas, “slavery persisted in Delaware and Kentucky, where the enslaved had to wait until the ratification of the 13th Amendment” to the Constitution of the United States.

“Even then people of African descent weren’t even free to celebrate Juneteenth in public spaces, so they bought their own parks, and they brought the celebration into the church where it belongs,” he said.

Taylor has said that in 2023 diocesan programming will focus on racial reconciliation. He added: “For those most wounded by the sin of slavery our nation holds justice at bay in too many ways to count, and yet we must count them, and count them we shall.”

Imagining himself among those hearing Granger’s General Order 3 that day, Taylor added, to hearty applause, “I like to imagine and pray by God’s grace that the hearts of the oppressed swelled with hope, hope that better days of freedom, justice and peace were coming. We’re still waiting. But hope won’t die. I give thanks for all the voices lifted in prayer and song today … for all God’s people may justice, freedom, and peace rise and rise and reign.”

U.S. President Joe Biden signed legislation a year ago proclaiming June 19 a federal holiday, which took effect this year, according to a statement from the White House.

“It is a day of profound weight and power that reminds us of our extraordinary capacity to heal, hope, and emerge from our most painful moments into a better version of ourselves,” the president said in the statement. “Great nations don’t ignore their most painful moments. They confront them to grow stronger. And that is what this great nation must continue to do.”

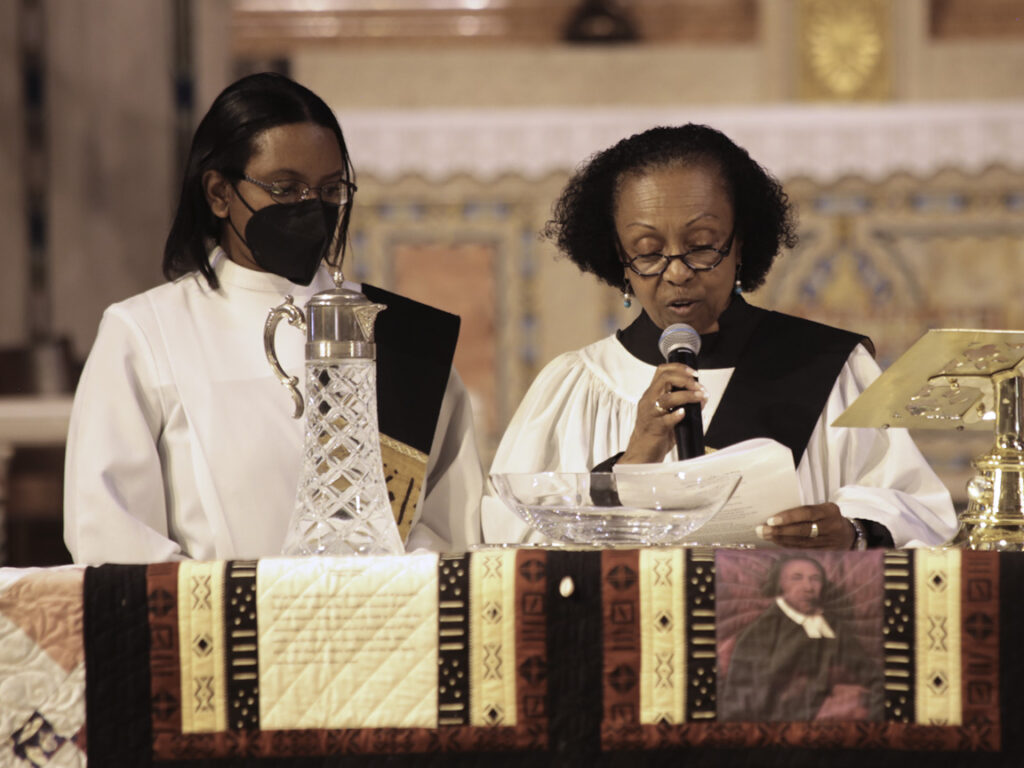

The Rev. Margaret McCauley led a libation ceremony, an offering of drink, usually water, to ancestral spirits, in homage to the African tradition.

“This water represents the Holy Spirit of God, prophetic healing, prosperity and the living waters that flow from a spring of water gushing up to eternal life,” she said, as fellow deacon Dominique Piper poured water into a bowl at the altar.

“We pour these libations in gratitude to God for our ancestors, who built civilizations, survived the horrors of the Middle Passage, who stayed faithful to God through slavery, who maintained their dignity in the face of physical and psychic violence, who lived, laughed, and who gave us life,” said McCauley. “In the name of Jesus.”

She also invoked the seven principles of African communal life: “Umoja (unity), Kujichagulila (self-determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics); Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity) and Imani (faith).” These principles are also celebrated each year at Kwanzaa (Dec. 26 – Jan. 1).

Deacon Margaret McCauley and Deacon Dominique Piper lead a libation ceremony adapted from an ancient African custom.

In song and spoken word, Qwendolyn Price performed “The Negro Mother,” a poem written by Langston Hughes, a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance.

In the poem, published in 1931, the mother speaks to her children, as an ancestor to Black Americans, describing hardship and struggles during the slave trade and slavery and challenging them to pick up the torch and to carry it, to continue fighting for freedom and equality.

Price was accompanied by the Episcopal Chorale, directed by Canon Charles “Chas” Cheatham, who recently retired to Georgia, but flew to Los Angeles to take part in the Juneteenth celebration.

The Rev. Guy Leemhuis, who serves at St. Luke’s of-the-Mountains in La Crescenta, continued that theme during a sermon frequently interrupted with applause and “Amens” from the congregation.

He offered “a context for why we all we need to celebrate Juneteenth regardless of color, creed, race, national origin, sexual orientation. We all can learn a lesson and celebrate the freedom obtained by the descendants of slaves.”

Especially, he said, in a time when simply telling the truth about the nation’s history—especially regarding slavery and racism—is under attack in many places. About 23, or nearly half of all U.S. states, are in the process of banning or restricting teaching critical race theory, which holds that race is a social construct, and racism is not merely the product of individual bias or prejudice, but also something embedded in legal systems and policies. (Critical race theory is not, in fact, taught in elementary, middle or high schools, but only at the graduate university level.)

“We need to have truth telling before we can get to a reconciliation,” Leemhuis said.

Acknowledgement also must be made about The Episcopal Church’s complicity in slavery, “a church that regularly funded the ships to go pick up my siblings and bring them over here in forced slavery.

“You can look in church records and find that, in the retirement of priests, some of them were given slaves as part of their retirement,” he said. Referring to Taylor’s remarks, he added: “So, as the bishop said, it is apropos that we, more than anyone, as the church, need to be celebrating Juneteenth.”

The Rev. Guy Leemhuis delivers a sermon at the Juneteenth Evensong. “We as a people have been ‘invisibalized’ for hundreds of years, all the way up to today,” he said. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

He noted that slavery’s impact is sometimes diminished by the notion that it’s ancient history. Yet, its legacy of trauma continues through the present, in an increasingly negative political climate. For example, a modern narrative blames people of African descent for systems that have rendered many educationally, financially and socially impoverished. Such narratives, Leemhuis said, have “invisibalized” them.

“It means to intentionally make a person invisible. We as a people have been invisibalized for hundreds of years, all the way up to today,” he said. Truth-telling countering that narrative must happen before reconciliation can occur, he said.

He cited the slave labor that built the White House; the destruction of Tulsa, Oklahoma’s Greenwood District, known as Black Wall Street, that was destroyed by a white mob on May 31, 1921; and such personalities as Madam C.J. Walker, a hair care entrepreneur in the early 1900s, who is recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records as the nation’s first self-made female millionaire.

Leemhuis also cited African American political participation during Reconstruction, a period of time after the Civil War, when some 2,000 African Americans held public office, both locally and nationally.

“We are people who make something out of nothing,” Leemhuis said amid enthusiastic applause. “There has been such misinformation of our history. We can’t make this right until we tell the truth, because if we continue to perpetuate the lies, that keep people degraded and oppressed, we can never be reconciled.

“If you’re sorry, say you’re sorry, mean you’re sorry, behave like you’re sorry,” he added. “Repairing the breach doesn’t mean anything unless you put action to it. Reparations are an action.”

Pointing to a nearby icon, depicting Jesus as Black – painted by the Rev. Canon Warner Traynham, retired St. John’s rector – he added that the image of Jesus as white is a false narrative that must be dismantled before reconciliation can occur.

“We all need to celebrate, to teach, because we need to hear the promise of Jesus who said it’s time to set the captives free. It’s time to recognize that we’re all God’s children.”

Dismantling white supremacy involves being humble and listening, he said, and working together to understand the false narratives that have dominated American culture and life.

Such false narratives as: “Some of us in a certain generation were told we’d never amount to anything,” he said. “We were told we had to work twice as hard as white people. You can’t get to beloved community without doing the hard work.”

Also present was a display of quilts by the Rev. Canon Jamie Hammons, a member of the Union of Black Episcopalians, and the African American Quilters of Los Angeles.

Hammons said her father, a tailor, taught her to sew. Among the quilts displayed was one dedicated to the jazz tradition in Black American culture. Another was dedicated to Absalom Jones, which she designed and made in response to a call from the Los Angeles UBE chapter to be creative in celebration of the Feb. 13 commemoration of Jones, the first African American ordained a priest in The Episcopal Church and the founder of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia in 1792, the first African American Episcopal Church in the U.S.