Sharon Crandall, director of Prism, prays with an inmate at Men’s Central Jail in Los Angeles. Photo: Chris Tumilty

[The Episcopal News] For Prism staff and volunteers, the need to be companions and to share communion with those in local jails and detention centers in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic has never been more urgent or more rewarding.

“People are daunted by the issue of incarceration, but that’s not what we’re doing,” says Ann Noble, program coordinator of Prism, the restorative justice ministry of the Diocese of Los Angeles. Often, she says, “it’s just one human being talking to another human being and sharing a story. So, it’s the biggest deal, and yet it’s not a big deal. It feels like it requires so much and all it requires is the greatest gift you have, which is your presence, and everyone can give that.”

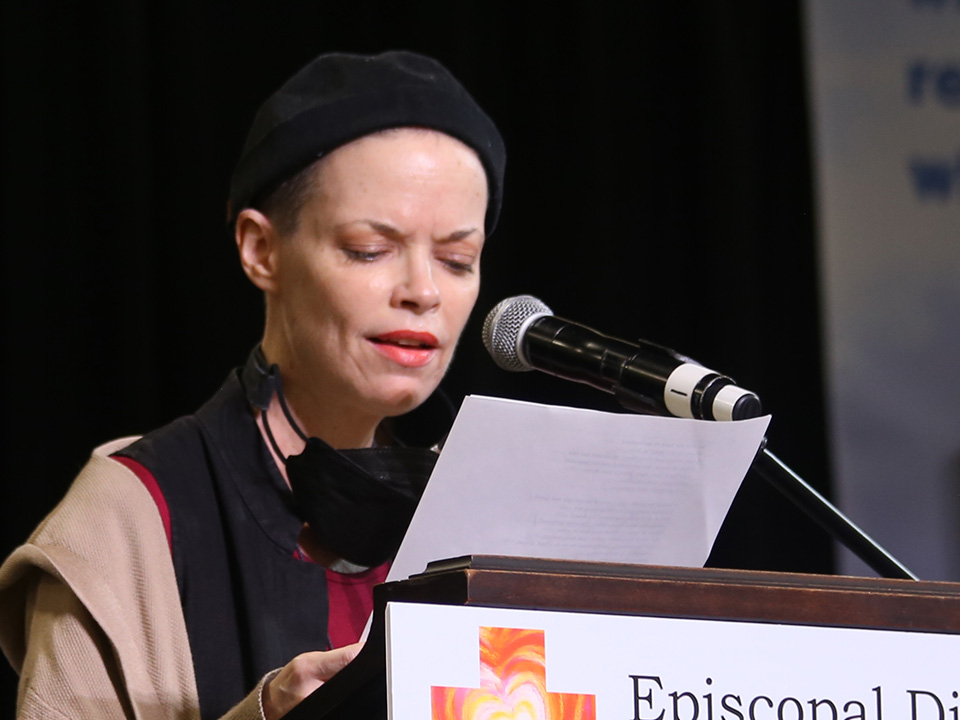

Anne Noble of Prism reads a poem during noonday prayer at Diocesan Convention 2021. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

While visiting those confined to Twin Towers, the Men’s Central Jail, and the Century Regional Detention Facility in Lynwood can seem scary, “an encounter can be sitting one-on-one with one person,” she said. “It can also be participating in a small service, a mass, just a small group of people in a circle.

“We don’t preach at them, we share. So it feels much more communal. We don’t get up at a podium and talk at them, we sit with them.” With Eucharist, she said, “there’s an opportunity to share the bread, an opportunity to anoint with oil, an opportunity to sit and chat.”

Continuing Covid restrictions have limited the Sunday gatherings to about 10 people, and “that really cuts our numbers down,” according to Sharon Crandall, Prism director. But as soon as the jails re-opened to visitations, Prism was back, she said, because “it’s about the people we serve.”

Prism has recently shifted its base of operations to All Saints Church in Pasadena, a move that the Rev. Mike Kinman called “a natural partnership.”

“One of the first things I did when I got here, before I officially started as rector in October 2016, I went to a Prism fundraiser and learned about the ministry,” he said. “Literally, the next day I called [the Rev.] Dennis Gibbs and said, this is something I feel I need to do, particularly as a congregation that skews wealthier and more privileged.”

Sharon Matsuhige Crandall is director of Prism, jail ministry of the Diocese of Los Angeles. Courtesy photo

Since then, former Prism directors Gibbs and the Rev. Greta Ronnigen, co-founders of the Community of Divine Love, have relocated their monastery to the San Luis Obispo area. After their departure, Noble and Crandall, who were long-time volunteers, assumed leadership roles.

“If we’re truly going to be God’s beloved community, then we need to be actively involved in places where some of the least privileged members of our society are,” Kinman said. “And not in terms of ‘we need to go help them,’ but because that is where Jesus is.

“I am hoping that this is a ministry that draws our congregation more and more into those places where Jesus lives,” he added. “It’s also a ministry of the Diocese of Los Angeles and any way that All Saints Church can reach out and help the mission and ministry of the diocese, that’s something we need to do, because we’re all in this together.”

Crandall said having a home base is important, both logistically and spiritually. “When we do a church service and talk about community and share the bread that was consecrated that morning at the church, it means something to those we visit. I think we underestimate the power of that kind of connection for people who are incarcerated.”

For example, “a man named George, who was baptized in the jails, is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole. We baptized him at the jail. He just lights up when he shows people that baptismal certificate and tells people he’s a member of the church.

“It’s important for someone like George, who knows he’s going to spend the rest of his life in prison, to feel connected to a greater spiritual community.”

Crandall added: “Now, without the monastery, we need that support. This is not necessarily easy work to do. When I go into the jails, I’m by myself most of the time during the week and it’s nice to feel like you have that community of support behind you.”

Episcopal ministry uplifts LGBTQ+ inmates

All Saints parishioner and Prism volunteer Tim Hartley says his experience in the jails helped form his decision to seek ordination.

“It is an amazing, fulfilling ministry,” Hartley said. “The people who come to the service seemed moved by it, and I was changed by it.”

For many of the incarcerated, especially the LGBTQ+ community, Prism brings “genuinely good news, because there are a lot of organizations that will go in as chaplains to the jails in order to convert people to their denomination or particular faith, with the idea of saving souls,” he said.

“Prism is one of the few organizations that will send chaplains in the LGBTQ floor of Twin Towers.”

He recalled a county-led training session for volunteers, where prospective chaplains were hesitant to call inmates by their preferred pronouns, especially if those pronouns “might differ from the way they look or the jail they’re in. One even asked if they could just call them by their inmate number.

“All that is to say the work Prism does is bringing genuinely the good news that we’re supposed to be bringing as Christians.”

All Saints Church, Pasadena, is the new home base for Prism’s ministry. File photo

Prism volunteer Jonathan Stoner, 40, who also serves as a City of Hope chaplain, agreed, saying he jumped at the chance to return to the jails once Covid restrictions were lifted.

“How cool, to be part of a ministry truly serving the least of these, that even other churches don’t want to minister to. Those experiences, doing services with folks who are LGBTQ+ in the jails, have been really meaningful.

“The folks who come to the services are so hungry, so open, so involved, and serious. They’re engaged in reading. They ask great questions and bring their own knowledge of the scriptures and their own experiences in the conversations.”

Social justice and the ministry of Prism is “part of All Saints’ DNA,” Stoner added. With Crandall and Noble as leaders, and with Mike Kinman at the helm of All Saints, “Prism is going to be championed and hopefully we can get more people involved and even expand to other jails and other prison systems,” he said.

“We can continue to reimagine what this ministry could look like and what the Spirit could be moving us in this season of pandemic.

Serving those in jail “feels like a sacred obligation, a calling,” he said. “It is a reminder to me that each of us has dignity as human beings. Each has worth as children of God, regardless of what we’ve done, or will do. We are all worthy of love and deserve a second chance, a third, a fifth chance.

“There is this sense that this is where I need to be on Sundays, with the people Jesus would be hanging out with.”