The Rev. Canon Malcolm Boyd — whose human rights advocacy shaped most of his 30 books including the 1965 best-seller Are You Running With Me, Jesus? — died Feb. 27 while receiving private hospice care in Los Angeles. Severe complications of pneumonia caused Boyd’s death at age 91, said his life partner, Mark Thompson.

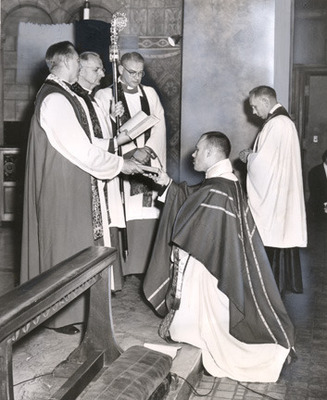

Boyd was ordained 60 years ago in the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles which he served since 1996 as writer-in-residence. Bishop F. Eric Bloy made Boyd, then age 31, a deacon in 1954 and a priest the next year. Ordination followed Boyd’s work in television’s early years as a production partner of Hollywood icon Mary Pickford.

“Malcolm lives on in our hearts and minds through the wise words and courageous example he has shared with us through the years,” said the Rt. Rev. J. Jon Bruno, bishop of the six-county Diocese of Los Angeles. “We pray in thanksgiving for Malcolm’s life and ministry, for his tireless advocacy for civil rights, and for his faithful devotion to Jesus who now welcomes him to eternal life and comforts us in our sense of loss.”

Activism for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered equality was at the core of Boyd and Thompson’s 31-year union, which included their civil marriage in a July 2013 private ceremony in their longtime home in the Silver Lake section of Los Angeles.

A Eucharistic celebration of Boyd’s life will be held at 2 p.m. on Saturday, March 21, at the Cathedral Center of St. Paul, 840 Echo Park Avenue, where he also conducted spiritual direction and mentoring with several clergy and lay persons. There he completed the most recent of the 30 books that he wrote and six that he edited in addition to writing numerous columns, essays, sermons and prayers after being named diocesan writer-in-residence by Bishop Frederick H. Borsch.

Running with Jesus

Active in ministry through the recent Christmas season, Boyd was preparing to mark the 50th anniversary this spring of the publication of his landmark book of prayers, Are You Running with Me, Jesus? In December he wrote that the book “had for a long time been slowly growing in my soul, mind and being. This came to a head when a group of Roman Catholic priests and laity invited me to be their guest on a visit to Jerusalem and Rome. We were very open to one another in our spiritual quest. One afternoon as a group we were resting. I did something that changed my life; I wrote a short prayer on an airline ticket. It became the first prayer in my book, which appeared a year later.”

“It’s morning, Jesus,” the book’s signature prayer begins. “…I’ve got to run all over again. / Where am I running? You know these things I can’t understand… / So I’ll follow along, OK? But lead, please. Now I’ve got to run. Are you running with me, Jesus?”

The story of Boyd’s life — including marching in Selma for civil rights and publicly coming out as gay, in a 1977 interview with the Chicago Sun-Times religion editor — is being chronicled in a new documentary titled Malcolm Boyd: Disturber of the Peace and set for completion later this year. Full information is available online here. Memorial contributions are being received, through the Diocese of Los Angeles, to complete the film.

Boyd’s decision to pursue ordained ministry, following his paternal grandfather who was also an Episcopal priest, came after several years of working in Hollywood and New York in radio and television. In 1944 Boyd enrolled in a radio workshop conducted by NBC in Hollywood. He was hired thereafter by the advertising agency Foote, Cone & Belding and became a junior producer of radio and television programs. In 1947 he left advertising to begin work as a writer and producer for Republic Pictures and Samuel Goldwyn Productions.

In the course of this work, Boyd met Pickford and her third husband, Charles “Buddy” Rogers, and joined the couple to form, in 1949, the production company PRB Inc. In 1951, with Pickford’s support, Boyd began seminary studies in Berkeley, Calif., at the Church Divinity School of the Pacific, which awarded him an honorary doctorate in 1995.

Pickford and Boyd’s association is cited in Eileen Whitfield’s 1997 book Pickford: The Woman Who Made Hollywood. Another family friend, actress Lillian Gish, was close to Boyd and his mother, Beatrice, who was for several years parish secretary at St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church in Hollywood.

Early life and ministry

Boyd was the only child of investment banker Melville Boyd and Beatrice Lowrie, a fashion model, who were married in the early 1920s. Malcolm was born on June 8, 1923, in Buffalo, N.Y., where his parents were visiting from their Manhattan home. The family’s fortunes perished in the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, and the couple’s marriage ended in divorce. Beatrice Boyd moved to Colorado Springs, accompanied by young Malcolm, who developed an interest in journalism by writing for school newspapers, later crediting middle- and high-school teachers as early and influential mentors.

It was at St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral in Denver that Boyd and his mother encountered Dean Paul Roberts, who encouraged Boyd to consider the priesthood. After ordination, Boyd credited Roberts as one of his greatest spiritual guides. While in college, Boyd contracted bronchiectasis and doctors recommended a change of climate, which led to his enrollment and graduation in 1944 from the University of Arizona at Tucson.

Following his 1955 ordination, Boyd pursued further studies at Oxford University and in Geneva at the World Council of Churches’ Ecumenical Institute. In 1956 he earned a master’s degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York. He wrote his first book, Crisis in Communication, and in 1957 traveled to France to serve in the Taizé community.

After returning to the United States, Boyd was called as rector of St. George’s Church in inner-city Indianapolis. It was here in 1957 that Boyd met Paul and Jenny Moore and became close friends. At the time, Paul Moore was dean of Christ Church Cathedral, Indianapolis, prior to his 1964 consecration as bishop suffragan in Washington D.C. and his 1969 election as bishop coadjutor of the Manhattan-based Diocese of New York.

Boyd’s second book, Christ and Celebrity Gods, was published in 1958, tracing the development of the Hollywood “religious film” including several produced by Cecil B. DeMille, a fellow Episcopalian whom Boyd interviewed at various times, differing on some points of view.

‘Espresso Priest,’ Freedom Rider

In 1959 Boyd became Episcopal chaplain at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, where he began a coffeehouse ministry known as “The Golden Grape” and later became identified in the media as “the espresso priest.” His outreach to the “beatniks” drew criticism from Colorado’s then-diocesan bishop, Joseph Minnis, and Boyd eventually resigned as chaplain. Later in 1959, during an address for the Religious Emphasis Week at Louisiana State University, Boyd gave a clear call for an end to racial segregation and began a decade of work in the civil rights movement.

In 1961, Boyd joined 27 other Episcopal priests — black and white — in a Freedom Ride organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in an effort to desegregate interstate transportation. In 1962 Life magazine named Boyd among the “100 Most Important Young Men and Women in the United States.”

From 1961 to 1964, Boyd served concurrently as priest on the interracial ministry team of Grace Church, Detroit, and as Episcopal chaplain at Wayne State University. In the summer of 1965 he assisted with voter registration in Mississippi and Alabama. Later in 1965 Boyd was present in Los Angeles when the Watts riots erupted, assisting in local ministry at the direction of Bishop Bloy. Boyd’s friend, Jonathan Daniels, was murdered in Alabama that summer, on Aug. 20.

Boyd, second from right, and other Episcopal clergy visit a church destroyed during 1960s civil unrest.

When Boyd’s Are You Running with Me, Jesus? was published in 1965, “no one knew it would become a runaway national bestseller with one million copies in print and translation into a number of different languages,” he later said, recalling that he “gave many public readings from the book accompanied by musicians including Oscar Brown, Jr., Vince Guaraldi and guitarist Charlie Byrd.” Columbia Records released two albums of Boyd and Byrd collaborating. Boyd also read the prayers in San Francisco’s hungry i nightclub, with Dick Gregory headlining the bill through a one-month run.

Boyd went on to assist until 1970 at the Church of the Atonement, Washington D.C., where he also served as field director for the Episcopal Society for Cultural and Racial Unity. On February 6, 1968, Boyd was present a final time in a rally with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., a gathering near the Tomb of the Unknown Solider in Arlington Cemetery.

“In the 1960s, Boyd began to edge out of the closet,” notes the online “glbtq encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, & queer culture.”

“He had experienced his first sexual relationship with another man in New York City in the mid-1950s but hesitated to accept his homosexuality,” the online encyclopedia continues. “He came out unofficially in 1965 with his eloquent prayer ‘This is a Homosexual Bar, Jesus’ in Are You Running with Me, Jesus? The book led to an offer in 1968 to become writer-in-residence at Calhoun College of Yale University.”

The encyclopedia adds that when Boyd came out publicly in the 1977 Chicago Sun-Times interview he became, by some accounts, “the first prominent openly gay clergyman of a mainstream Christian denomination in the United States. He also discussed the difficulties of being a gay Episcopal priest in his autobiography, Take Off the Masks (1978). In Gay Priest (1986), Boyd explored the painful spiritual journey forced upon any gay man who would be a priest.”

Nexus of sacred, secular

Popular television hosts Dick Cavett and Merv Griffin were among those who interviewed Boyd on the air through the 1960s and into the ’70s. A July 27, 1971 Look magazine cover story pictured him among 16 Americans — including Margaret Mead, Walter Cronkite, Duke Ellington and Norman Vincent Peale — each offering his or her “personal key” to peace of mind. During these years Boyd also developed a friendship with Hugh Hefner, and the two collaborated in interviews and events, some at the Playboy Mansion in Los Angeles.

Amid such secular contexts, Boyd also claimed “no intention of severing his connection with the institutional church,” the Diocesan Press Service, now Episcopal News Service, reported in 1969. “The best-selling author said he had a ‘Virginia Woolf kind of marriage to the Church. It’s violent, it’s lusty, it’s organic. A divorce would be out of the question. We would always be in one another’s fantasies.”

Some 30 years later, at a 1999 San Diego meeting of the Episcopal Church’s House of Bishops, Boyd and Thompson were present to comment on the depth of their relationship and to advocate for marriage equality. On May 16, 2004, Bishop Bruno blessed Boyd and Thompson’s union in a ceremony at the Cathedral Center on the 20th anniversary of their life partnership.

In 1996, Boyd concluded 15 years as an associate priest at St. Augustine by-the-Sea Episcopal Church in Santa Monica. During these years Boyd served three terms as president of PEN Center USA West, the regional center of the international writers’ organization, and was a frequent book reviewer for the Los Angeles Times.

From 1990 to 2000, Boyd also wrote a regular column for Modern Maturity, magazine of the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) with 34 million readers. From 1996 until his death he was a columnist for The Episcopal News. In 2011, Boyd became a regular columnist in the Huffington Post’s religion section, continuing through 2014 and often commenting on how much he enjoyed contributing online and in the context of social media. A link to the columns is here.

Insights on death, dying

The death of Boyd’s mother in 1997, just 10 days before her 99th birthday, prompted his book Go Gentle Into that Good Night (Genesis Press, 1998), a reflective commentary on death and dying.

In Go Gentle, Boyd wrote: “I hope I’ll have few regrets when death comes. I would like to walk away hand in hand with death, feeling that I have struggled faithfully with the key issues that presented themselves to me. I hope that I will not cry or whine for more time. If I have used my time for love, and am eager to find what lies ahead, I won’t have to.”

Later, Boyd’s essay titled “Mother Broke Her Hip” was included in the book In Times Like These … How We Pray, a volume that Boyd edited with Bishop Bruno. With Los Angeles Bishop Suffragan Chester Talton, Boyd also co-edited the 2003 book Race and Prayer: Collected Voices, Many Dreams. In 2011, to coincide with Boyd’s 88th birthday, Seabury Books published Black Battle, White Knight: The Authorized Biography of Malcolm Boyd by the Rev. Canon Michael Battle — with a foreword by Nobel Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who wrote: “One is an octogenarian, and the other a late baby boomer. One is heterosexual, married with three children, and the other is gay in a long-term partnership. One is black and the other is white. But the similarities far outweigh the differences, the chief similarity being their mutual search for God here and everywhere.”

In advance of Boyd’s 90th birthday, the Lambda Literary Foundation hosted OUTWRITE!, a special celebration honoring Los Angeles LGBT literary pioneers — Malcolm Boyd, Lillian Faderman, Katherine V. Forrest, John Rechy and Patricia Nell Warren — at the West Hollywood Public Library. The April 27, 2013 event marked the organization’s 25th anniversary.

That spring, a Christian Science Monitor profile written by journalist Gary Yerkey noted Boyd’s expertise in conveying “the message of Christianity outside of the walls of the church to champion minority rights and show that God is everywhere.” The full article is here.

In May 2014, Boyd received an honorary doctorate from the Episcopal Divinity School, located in Cambridge, Mass., near the campus of Harvard University. Coverage is online here.

One of Boyd’s last public appearances was at the October 26, 2014 evensong and dinner marking the 150th year of the Cathedral Center congregation in which he had been ordained 60 years prior.

Late 2014 found Boyd preparing for the 50th anniversary, in spring 2015, of the 1965 release of Are You Running with Me, Jesus? Anticipating this occasion, Boyd wrote: “My book of prayers clearly now belongs to the world. I know that. I love prayer and am grateful it is a powerful part of my life. I wish we could — or would — pray with more passion, greater sensitivity, even more passion. I identify with what a writer for The New York Times wrote about the prayers: ‘The eloquence of the prayers comes from the personal struggle they contain — a struggle to believe, to keep going, a spiritual contest that is agonized, courageous and not always won.’ I am grateful for his insight. I agree with him.’’

— Robert Williams is canon for community relations of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles and a former director of the New York-based Episcopal News Service.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Are You Running with Me, Jesus?

It’s morning, Jesus. It’s morning, and here’s that light and sound all over again.

I’ve got to move fast … get into the bathroom, wash up, grab a bite to eat, and run some more.

I just don’t feel like it. What I really want to do is get back into bed, pull up the covers, and sleep.

All I seem to want today is the big sleep, and here I’ve got to run all over again.

Where am I running? You know these things I can’t understand. It’s not that I need to have you tell me.

What counts most is just that somebody knows, and it’s you. That helps a lot.

So I’ll follow along, OK? But lead, Lord. Now I’ve got to run. Are you running with me, Jesus?

— Malcolm Boyd, 1965