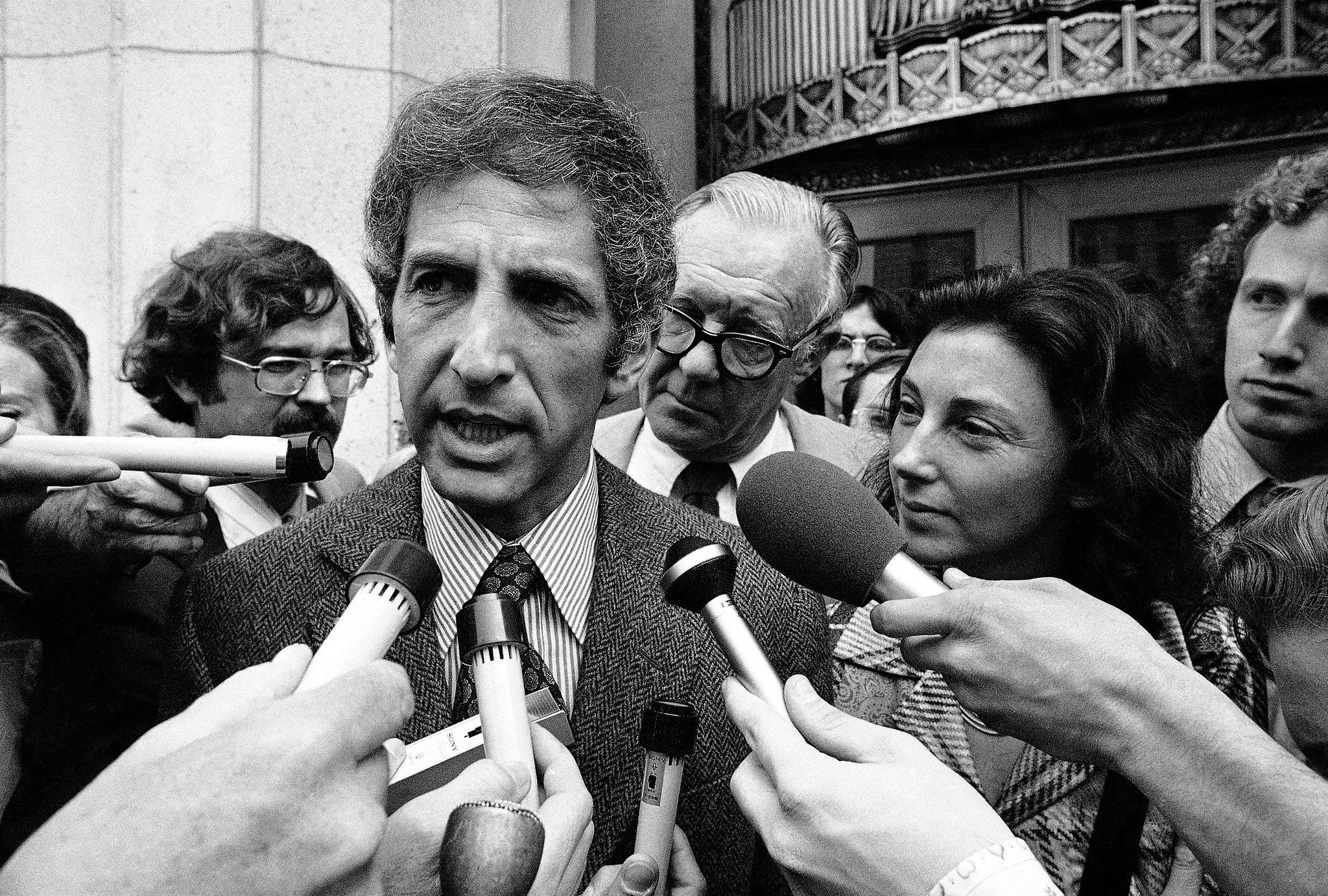

Daniel Ellsberg’s obituaries make clear that his leak of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 provoked the Nixon administration to a massive overreaction that led to Watergate and Richard Nixon’s disgrace.

It didn’t need to be that way. The Pentagon Papers helped us understand how we’d blundered into Vietnam during the Kennedy and Johnson years while revealing nothing about Nixon’s conduct of the war. By June 1969, within five months of taking office, he’d begun withdrawing troops, a policy called Vietnamization. Thinking more clearly, Nixon would’ve had Ellsberg over to dinner, invited him to headline a conference, and thanked him for revealing the incompetence of his predecessors. Instead Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s national security advisor, whipped the president into a frenzy of dread and class resentment.

With secret initiatives underway with Moscow and Beijing, RN and HAK were entitled to be anxious about what else Ellsberg or a copycat might do. During my years with Nixon, keeping secrets secret was the only issue he mentioned when he talked about Ellsberg. Still, one big leak wasn’t going to bring the government down. Sending burglars to read Ellsberg’s medical files, which the White House plumbers did in September 1971 as Watergate’s opening act, was an unforgivable abuse of power and a complete waste of time.

True, there were other motives for going after Ellsberg. Kissinger’s critics say he was afraid the public would learn of the U.S.’s secret bombing of communist sanctuaries in Cambodia, an ostensibly neutral country. Ellsberg himself said Nixon feared he would reveal his and Kissinger’s plans for escalating the war, but that doesn’t ring true. Nixon didn’t mind adversaries thinking he’d do something reckless. But he never seriously considered it. A determined pragmatist, Nixon realized that staying in Vietnam was a loser. So he was bent on getting out, though not as quickly as many would have liked.

Over 21,000 Americans died on his watch in Vietnam, which would have been a grave sin if done for political reasons. History may condemn him for it either way. Still, Nixon hoped South Vietnam would survive and wanted to vindicate those who’d fought and died already. If he’d left quickly, Saigon wouldn’t have had a chance. The towering irony is that Watergate kept him from maximizing the advantage he’d won by staying until January 1973 while building up South Vientam’s forces.

Again and again, Nixon the Machiavellian makes it hard for history to see Nixon the idealist. From Nixon estate-owned materials that, as his co-executor, I enabled scholars to see beginning in 2007, when the Nixon library became a federal installation, we’ve learned that Nixon was personally involved in efforts to thwart a Johnson administration peace initiative just before the 1968 election. LBJ’s bid had the whiff of a stunt to help the Democratic candidate, Hubert Humphrey. The South Vietnamese were already suspicious about it. But we only have one president at a time, and Nixon was wrong to get involved.

At the same time, we are entitled to wonder how involved in Vietnam we would have been if, eight years before, Nixon had beaten JFK and taken office in 1961. He became famous as an anti-communist. But by 1960 he was promoting the idea of strenuous economic competition between east and west along with more diplomatic engagement and people to people ties. Though cautious, even equivocal by nature, very much the son of his peace-loving Quaker mother, Nixon retained the reputation of a brawler like his father, with nothing to prove to Moscow or anyone else. It is hard to imagine him resorting to the blunt instrument of sending over half a million U.S. troops. It is also doubtful that the equally canny Kennedy would have done so if he’d been able to complete his presidency.

We can’t know for sure if Nixon or Kennedy would’ve found a different way. Instead, with the less deft Johnson’s massive escalation, Vietnam became another bloody proxy war — the U.S. and Soviets fighting without fighting directly — that wasted the lives of people of color. Korea had come before; El Salvador and Nicaragua came after.

When the Berlin Wall finally fell in 1989, wise heads prevailed in Washington, so it went down peacefully. No one wanted a war in Europe, for goodness sake. The west having won, the Cold War template, still largely unexamined by history, persisted. Hundreds of thousands died in Iraq and Afghanistan because Bush and Cheney, shamed by Sept. 11, mistook a jihadist criminal syndicate for a geostrategic threat, something that looked just enough like communism that you could fight a ground war against it in a developing country.

These days, the conflict in search of grand strategy is with China and Russia, bent on making ours the century of authoritarianism. No one wants that. The problem will be how to prevent it without annihilating the planet. Nearing the end of his life, Ellsberg argued that the U.S. and NATO had recklessly provoked Putin and worried that the Ukraine war will encourage China to threaten Taiwan, with all this conflict potentially leading to nuclear catastrophe.

A specialist in nuclear gamesmanship, Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers in part because he was afraid Nixon would escalate the war. Yet at the very time of the leak, Nixon was maneuvering to improve relations with Beijing and Moscow, hoping to deescalate Cold War tensions. Ellsberg was more principled than Nixon thought. He wanted to avoid nuclear war. Nixon was subtler than Ellsberg thought, because Nixon did, too. If they’d ever talked about it face to face, they might have figured out they had more in common than not. Which is almost always what happens when adversaries sit down and reason, reason, reason together. With the whole world at stake, may we do so soon.