When a Union general proclaimed in Galveston 159 years ago today that the enslaved people of Texas were at last to be considered free people, the Civil War was over. The so-called confederacy had ceased to be. But in the depths of Texas, which had entered the Union just 20 years before under the banner of enslavement, folks acted like nothing had happened – until the troops arrived.

Because the law was one thing. What those in power could still get away with was another. Saying people were free was one thing. Treating them with dignity was another. Saying people finally had to be paid for their labor was one thing. Coming up with two centuries’ back pay was another. Proclaiming the good news in Galveston was one thing. Living up to the standard of the good news of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is another.

Since the murder of George Floyd, my personal Juneteenth work has been to think about my privilege and about the work that remains undone these 159 years. Because one of Kathy’s and my children is working as a counselor in a Federal prison, where men of color are present all out of proportion to their share of the population, I’m thinking this year especially about the sins of mass incarceration and of treating addiction and mental illness as crimes. Millions are in jail because we’re still leaving people behind based on the color of their skin. We’re still not giving them a fair shake. We’re actually punishing them for being sick.

Some of us are heading to The Episcopal Church’s General Convention in Louisville next week. We have hundreds of resolutions before us – on racism, racial accountability, making the church better, more open, and more decent. We’ll have eight or ten on Israel and Palestine alone.

But prison reform? We have one resolution. Just one. And this is the church, mind you – the church to which Jesus actually had something to say about prisoners and captives. For many of our incarcerated siblings, it’s like they’re back in Texas, back in Galveston, waiting for the Union army – or the Spirit of God, like in the book of Acts – waiting for someone to break through the prison walls and proclaim that the prisoner is free at last.

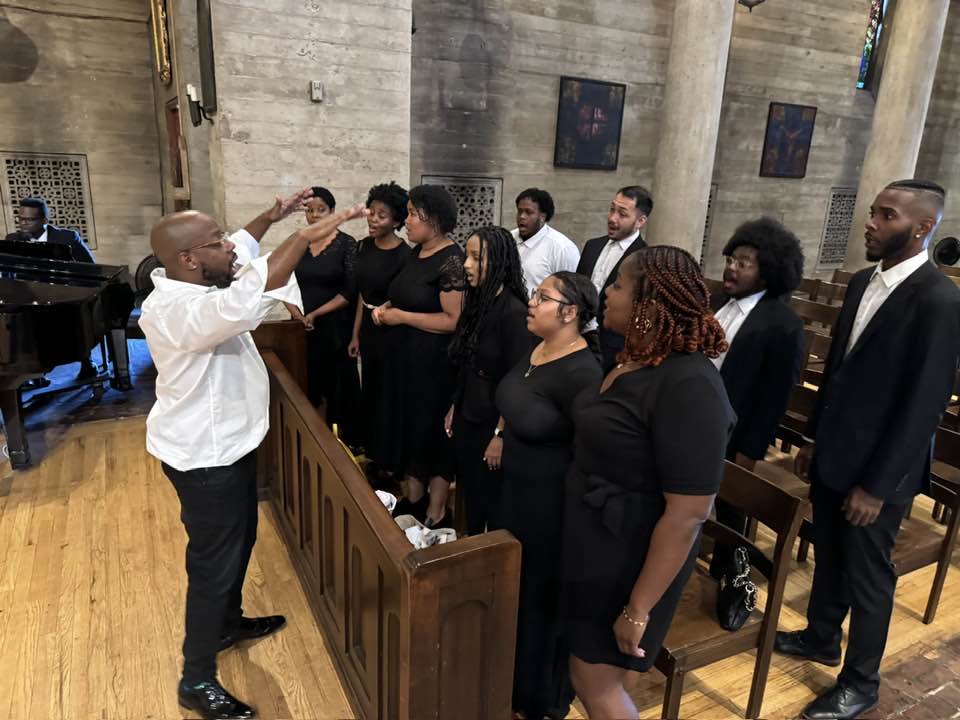

— My opening remarks at Saturday’s Freedom Day service at St. John’s Cathedral, hosted by the Program Group on Black Ministry and the H. Belfield Hannibal Chapter of the Union of Black Episcopalians. The Rev. Guy Leemhuis was our inspiring preacher, The Rev. Dominique Nicolette Piper our deacon. The Adrian Dunn Singers were world class. Our ears are still full of their joy in Christ. The Rev. Anne Sawyer, the cathedral’s interim dean, welcomed us warmly. Sexton Heyden Santiago assisted cheerfully. I was presider.