I’ve been thinking of Galveston, Texas as a crossroads of intersectionality — a kind of new Jerusalem, not in heaven but on earth. A place where God’s realm makes its comfortable earthly home.

I’ve been thinking of Galveston, Texas as a crossroads of intersectionality — a kind of new Jerusalem, not in heaven but on earth. A place where God’s realm makes its comfortable earthly home.

It was in Galveston where federal troops, on June 19, 1865, famously insisted that the Civil War was over. It had actually happened two months before, in April, at Appomattox Court House. When the south surrendered, slavery ended, by virtue of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

By June, the news had of course reached Galveston. They had received the living word of freedom via telegraph and newspapers delivered by mail. But authorities didn’t listen, because they didn’t have to — until the arrival of federal troops, the blades of their bayonets glinting in the sun. The soldiers marching through dusty streets drove the point home in a way that the local slaveholding gentry couldn’t ignore.

Another reason Galveston is calling to me is the old Jimmy Webb song, popularized by Glen Campbell. It’s one of Michael Stipe’s favorites. He’s the cofounder and lead singer of R.E.M. For your information, I consider Michael Stipe to be the coolest person on the planet. He says he was never closeted. Even in the hyper-masculine world of eighties rock ‘n’ roll, he lived his life openly and stood up for LGBTQ+ rights and the defeat of HIV-AIDS. Forty years ago, he took the view that inquiries about a person’s sexual orientation were anachronistic. Why waste time being obsessed with the gender of the person someone loves? It made far more sense to Stipe to be obsessed with knowing the music, photographers, and artists they loved.

Notwithstanding their arch hipness, R.E.M. used to perform “Galveston” in their shows. Webb wrote the song from the perspective of a soldier in Vietnam, imagining his love waiting back home:

Galveston, oh Galveston

I still hear your sea waves crashing

While I watch the cannons flashing

I clean my gun

And dream of Galveston

I think Michael probably loves this song because his father served in Vietnam, a terrible place of war where young draftees and volunteers dreamed of making it home to a beautiful place of love and peace. A place of intersectionality, where dreams and reality might conjoin for all God’s people.

This service is occurring in a unique moment of intersectionality. It’s of course the month of Juneteenth. It’s the month Trump went to war against immigrant workers and their families in the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles.

And it’s Pride month. In the realm of universal human rights, we thought we were getting somewhere in this country. But when the arc of justice does finally bend towards justice, fearful privilege seizes it in its grip and tries to bend it back. After a generation of hard won but steady gains, the queer community has had the worst half year in many years.

Politicians ruthlessly leveraged against the handful of trans and nonbinary athletes who compete at the high school, collegiate, or professional level. They took this tiny group of Americans, perhaps a few hundred, and sacrificed them on the altar of their will to power. They implied that the trans people were predators, coming for girls and women in the bathroom and locker room. They said that those who helped them were groomers. This was the dehumanizing language of hate. Trump’s executive orders on gender are preposterous. They’re also dangerous and life-denying.

Now the Supreme Court has called into question whether our trans siblings will have access to the healthcare they need and want. A government of the people, by the people, and for the people, a president pledged to do all they can for the largest number of our people — such a government would be well equipped to address complex social and medical questions in a way that took everyone’s interest into account, especially our trans and nonbinary siblings. Most of us have our opinions or prejudices. But it’s their life, their liberty, their pursuit of happiness.

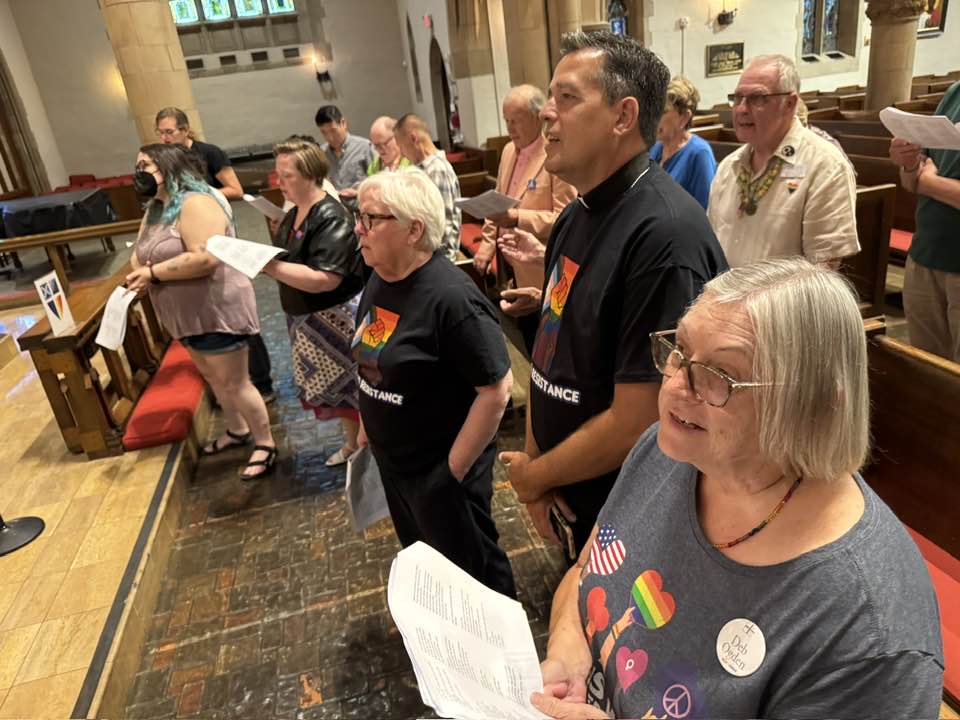

So our government does not stand with you today – but your church does. And when we gather, advocate, and pray, we are mindful of all in our community who are at risk in these times.

The church stands with our immigrant worker neighbors, demanding the regularization of our nation’s 13 million law-abiding undocumented immigrant workers, most of them people of color. We stand with young Black men stopped on city streets on suspicion of driving. We stand with all people of African descent, their heroes’ narratives erased from government websites. We stand with our AAPI siblings, scapegoated for COVID and perhaps at risk again if global tensions increase. We stand with everyone who isn’t white, male, and heterosexual when the TV personality in charge of the Pentagon berates reporters for asking questions about diversity.

As we gather in this sacred space, we imagine ourselves on the road to the new Galveston as bearers of the good news of Jesus Christ, like soldiers bearing the good news of freedom in 1865. The earthly city of the divine’s dream, where love reigns supreme, since love is the only thing that matters and the only thing that works. Where everyone has a place to lay their head, and no one is hungry. Where all the girls can play on girls’ teams and all the boys on boys’ teams. Where the government doesn’t draw its guns on Narciso Barranco, father of three United States Marines, and run him to ground in Orange County for the crimes of landscaping and feeding his family.

Where everyone looks at the face of their neighbor and every stranger, catches a glimpse of the face of God, and stands in awe. This isn’t utopianism. Humanity can accomplish it whenever we want. People just have to want it bad enough. We can get there anytime. But I don’t think we’ll make it unless the armies of Christ are marching to Galveston at the head of the line.

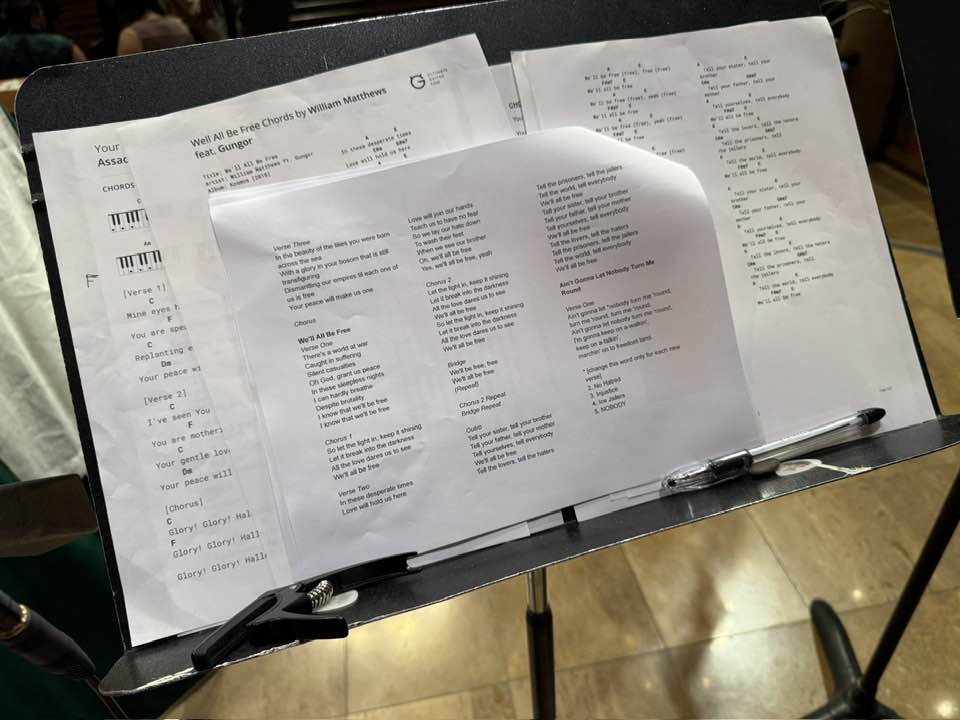

[My remarks and scrapbook from Sunday evening’s Pride Prayer Service at All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena.]