Diplomat, publisher, art collector, and philanthropist Walter Annenberg was both generous and thrifty. He gave $500 million in matching grants to the nation’s public schools and bequeathed impressionist and postimpressionist paintings worth over a billion dollars to the Met in New York. And when he called former President Nixon in his office in 26 Federal Plaza in lower Manhattan, he called person to person.

For the sake of those under 35: If you wanted, you could tell the long distance operator whom you were calling. No matter who picked up, you didn’t have to pay for the call unless your party was there. Maybe Annenberg put the savings in a cookie jar with a piece of masking tape that said “Monets and Picassos.”

Usually, of course, he called for Mr. Nixon. One day in early December 1987, he asked for me. As 37’s chief aide, I oversaw plans for the Nixon library in Yorba Linda, including the city’s efforts to put the land together. Annenberg kept an Associated Press teletype machine in his Philadelphia office. He’d just read a report about Edith Eichler, “blind but spry,” who lived in a house the city wanted to buy and bulldoze. Her and Mr. Nixon’s mothers had co-founded the Yorba Linda women’s club. She said that Richard had been “a nice enough little boy” and that she was sure he didn’t really want her consigned to assisted living.

In his rumbling, kindly baritone, Annenberg read the headline to me slowly: “Widow Being Booted Out Of Home To Make Way For Nixon Library.” Even now, it stands as a classic of the Snidely Whiplash genre of delectable villainy. Writing it must’ve been sheer delight. “I’ve been in the newspaper business a long time,” Annenberg said, “and when you’re reported as evicting a 97-year-old blind widow, you’ve got yourself a PR problem.” Within the hour, I was on the phone to city hall and the AP. The Eichler manse was saved.

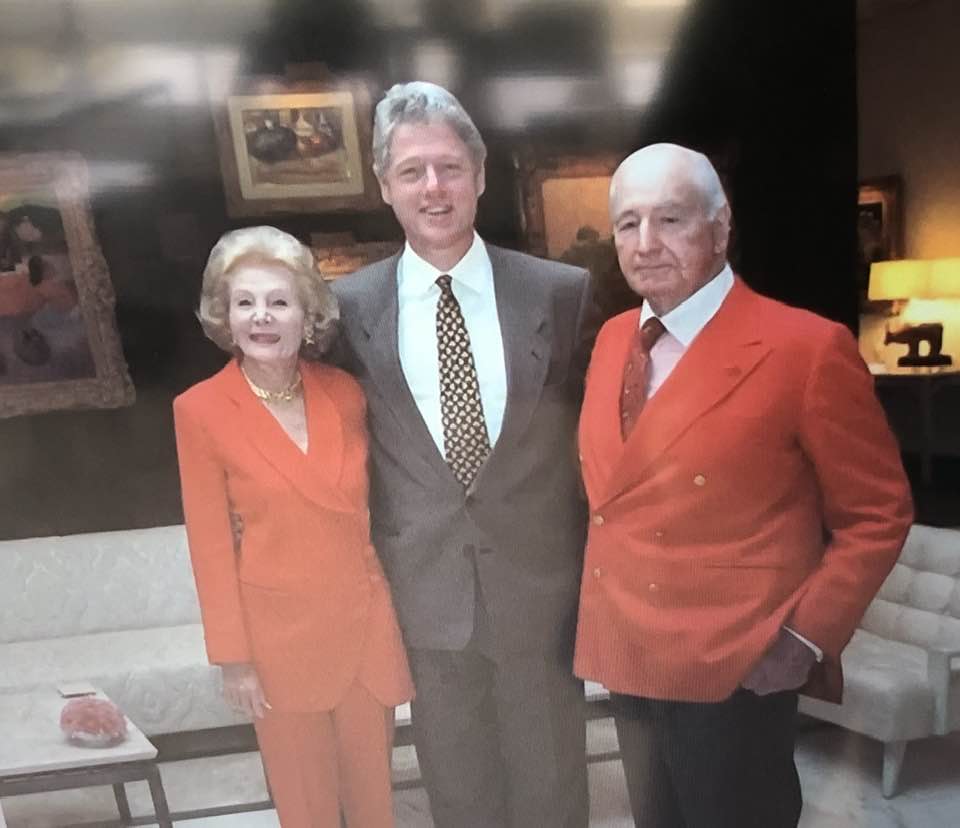

Kathy Hannigan O’Connor, Mr. Nixon’s last post-presidential chief of staff, and I exchanged this and other Annenberg stories today as we explored the Sunnylands visitor center in Rancho Mirage. Open free of charge, now run by a family trust, it expresses the spirit of welcome and gracious hospitality for which Walter and Lee Annenberg were famous. You can also buy tickets for a driving tour of the grounds and tours of the Annenbergs’ A. Quincy Jones-designed home, now used as a conference center.

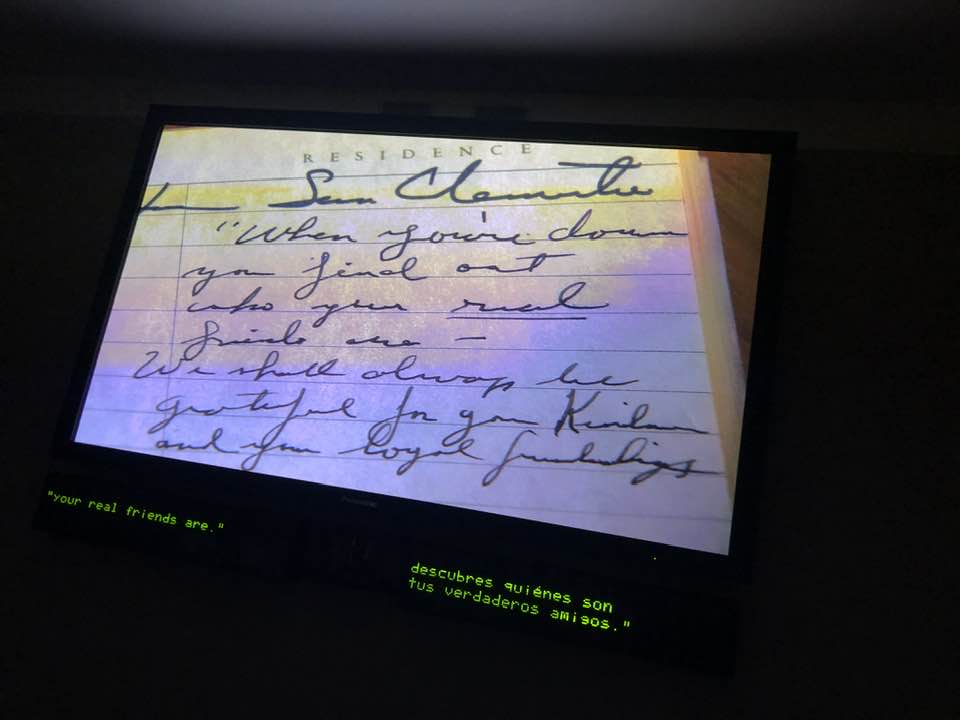

President Obama’s first meeting with China’s boss-for-life Xi Jinping took place at the house. So too a fictional meeting between Presidents Nixon and Ford in my little-noted 2014 novel, Jackson Place. Knowing how close both were to the Annenbergs, Kathy suggested the scene. A long line of presidents, Democratic and Republican, were welcome to rest, reflect, golf, and swim at Sunnylands. Mr. Nixon praised the Annenbergs’ “wholly unobtrusive thoughtfulness” as hosts.

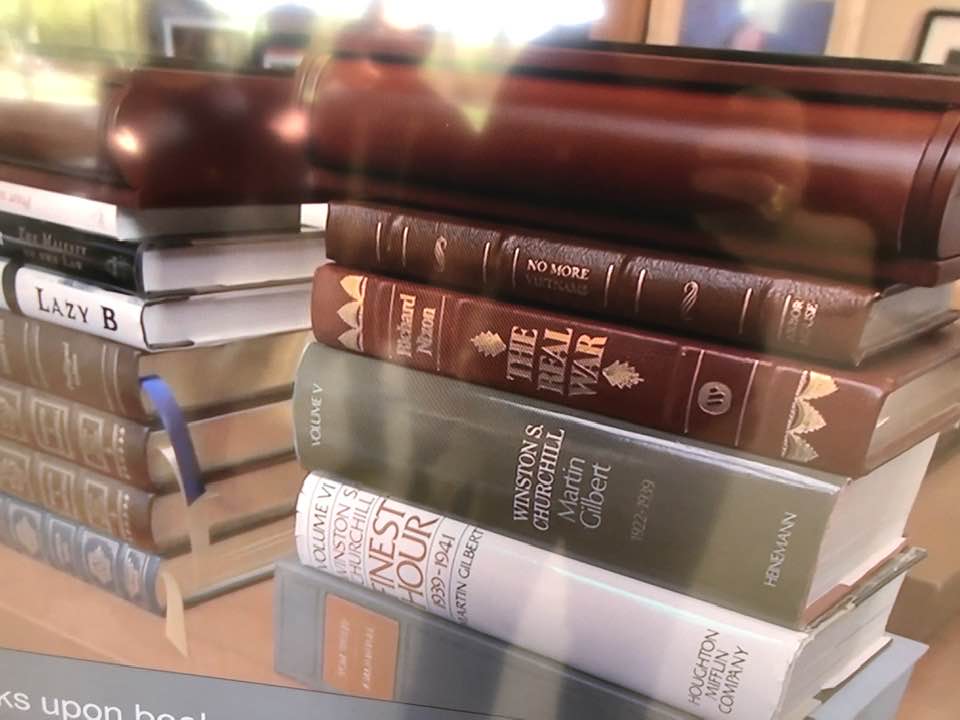

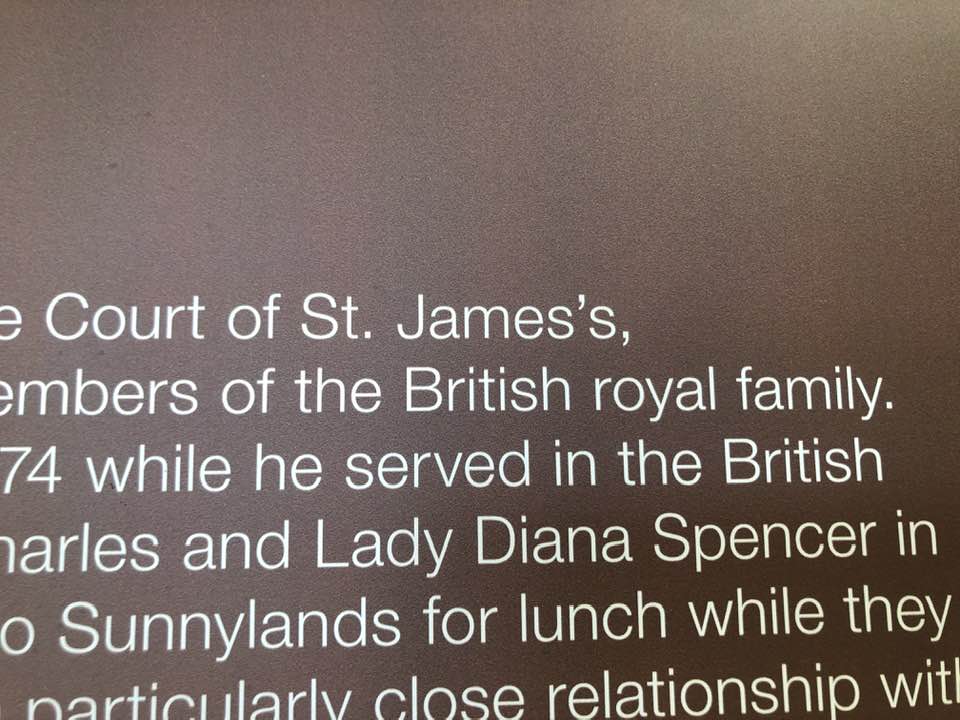

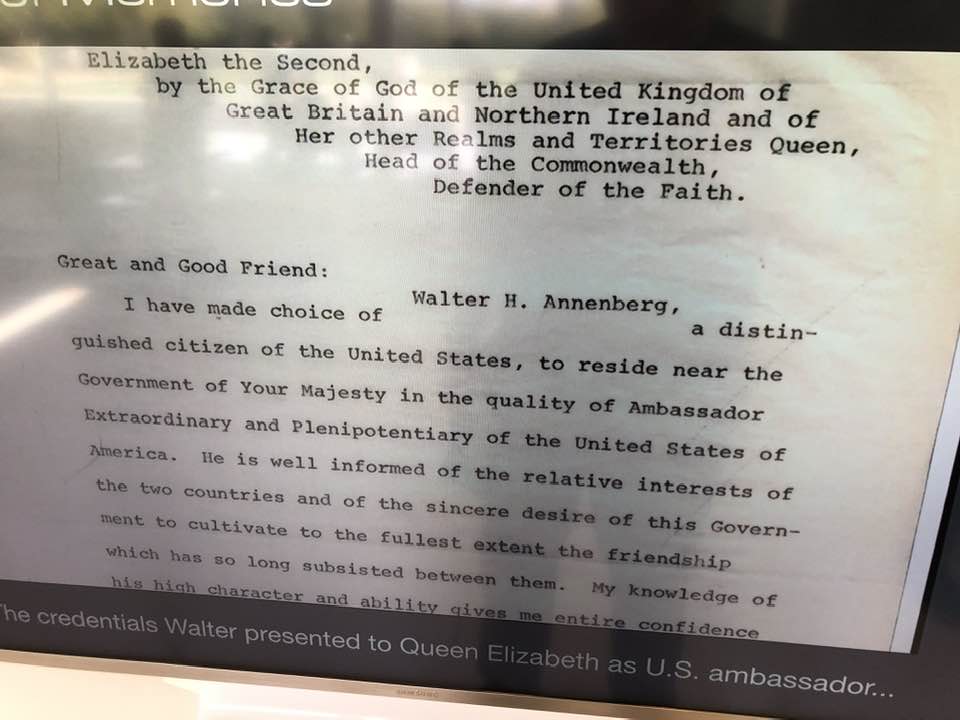

The Nixon-Annenberg friendship receives special attention in a 15-minute orientation movie. Annenberg’s father, Mo, did federal time. Walter made no secret about experiencing redemption when Mr. Nixon made him ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. If you question that punctuation, I have it from proofreader Annenberg himself, who nudged me when he saw a Nixon library caption reading St. James’. Further evidence of his shrewdness was selling his media empire, including “TV Guide” and “Seventeen,” which he’d founded, to Rupert Murdoch for $3.2 billion. This was in 1988, just in time for the death of print.

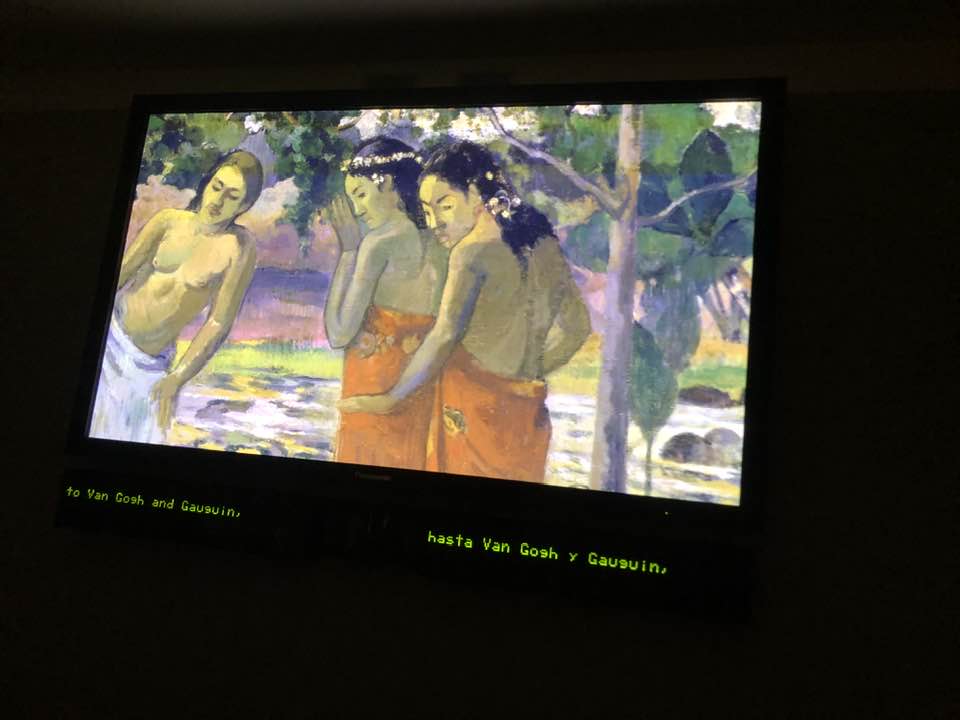

Kathy and I visited Sunnylands several times over the years, including with Mr. Nixon. On one occasion, it was as witnesses to one of the art world’s epic masterpieces of logistics. Annenberg had collected over 50 paintings and watercolors, which he said he loved like children. He gave them to the Met in the early nineties on the condition that, as long as he lived, he could have them back in the desert from December through May. He and Lee spent autumns and summers in Philadelphia and Colorado.

So every November, the Met took the paintings off the walls, packed them up, and shipped them to Rancho Mirage so that, when Walter walked in, it was as if they’d never left. One December morning in the late nineties, thanks to a friend on Annenbergs’ staff, a few days before the couple arrived themselves, Kathy and I got to see the collection up close, bathed in the desert light that flooded their home. Imagine our delight. When the ambassador died in 2002, his children at long last became permanent New York residents.

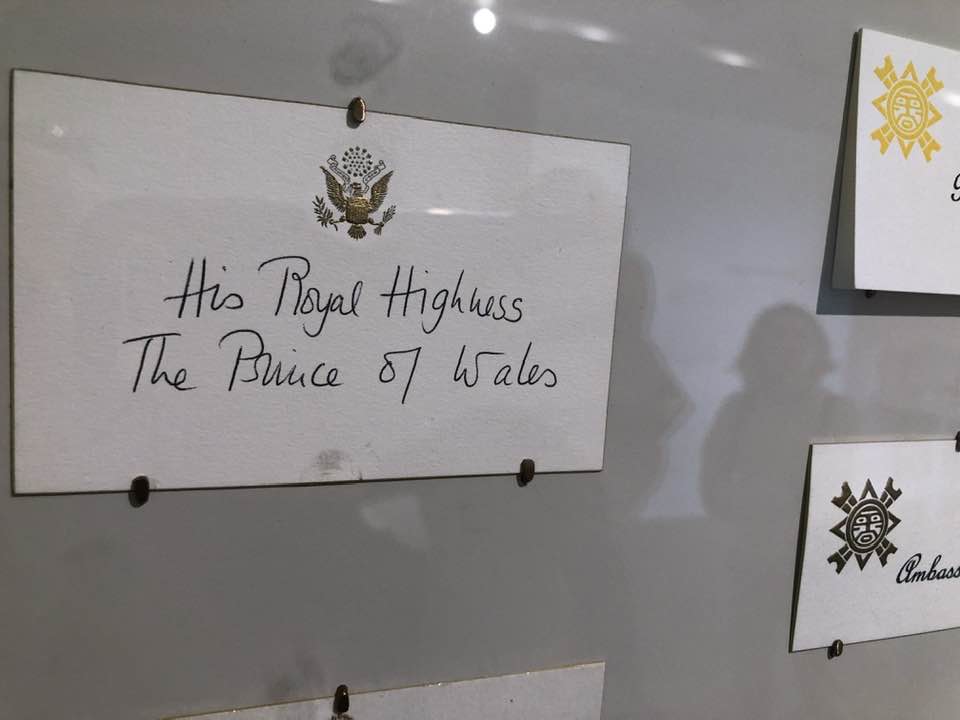

The trust (run by the Annenbergs’ flesh and blood family) and its staff have taken the same care curating the visitor center experience. Children climbed on furniture reminiscent of the Annenbergs’ living room. Exhibits include place settings, Lee’s handwritten place cards (she was chief of protocol for President Reagan), and golf balls sliced long ago and since recovered, including one of Mr. Nixon’s. The cafe even has newspapers and magazines for visitors to borrow while they eat.

The highlight of my visit, besides being there with Kathy, was the labyrinth, a feature the trust installed for us visitors’ sake. Not much of a contemplative, I learned about labyrinths from St. John’s Episcopal School chaplain Patti Peebles and Bloy House, The Episcopal Theological School at Los Angeles dean Linda Tolin Allport. Slow down, they always counseled. Let the Holy Spirit do her work.

So here I was, walking the labyrinth where the world’s most legendary overachievers once tread. And I did walk it slowly today, praying on the conjoining of my life’s seemingly irreconcilable vocational episodes, even as families with kids politely passed me on the left, hopped up on the fifth day of Christmas and the anticipation of Monday’s bowl games. And I felt Walter and Lee’s welcome still.