A group of some 25 interfaith leaders from Los Angeles traveled to San Diego and crossed the border to Tijuana Feb. 26 and 27 to learn more about how U.S. immigration policies affect the poor of Mexico. And learn they did, with a punch that left them determined to find ways to encourage effective immigration reform.

Bishop Suffragan Mary D. Glasspool of the Diocese of Los Angeles, with Fr. Alexei Smith, ecumenical and interreligious officer for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, and United Church of Christ minister Carlos Correa Bernier, executive director of the Romero Center, confer with one of the four nuns who operate Casa de Las Pobras (House of the Poor), a ministry to the destitute of Tijuana.

The group, which included Bishop Suffragan Mary D. Glasspool of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles, represented the Los Angeles Council of Religious Leaders (LACRL), and was led by Rabbi Mark Diamond, council president and regional director of AJC-LA, a local branch of a global Jewish advocacy organization.

The travelers also included clergy and lay representatives from the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, the California-Pacific conference of the United Methodist Church, the Southern California – Nevada Conference of the United Church of Christ and the Presbytery of the Pacific of the Presbyterian Church.

Beginning the first day’s presentations, Diamond reminded the LACRL group that the Old Testament constantly commands the Hebrews – and Christians — to welcome the stranger. He quoted Leviticus 19:33-34: “When a stranger resides with you in your land, you shall not wrong him. The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as one of your citizens; you shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt. I am the Lord and your God.”

Although there is a wide variety of opinions in the U.S. political arena on the complicated topic of immigration, Diamond said, “In 2013 we have a real shot at comprehensive immigration reform.”

Carmen M. Chavez, an immigration attorney and executive director of Casa Cornelia Law Center, a Roman Catholic ministry in San Diego that deals with immigration issues, agreed.

“I think for the first time my colleagues, not only at Casa Cornelia, but in the practice of immigration law, both the private and the nonprofit sector, for the first time in a long time are talking about immigration reform as if it might finally happen this time,” she told the religious leaders.

“We don’t know what it’s going to look like, but I do have to say that it’s going to stretch all of us,” she said, pointing out that implementing any new policy is going to take many years.

The role of faith communities in finding humane, workable solutions will be huge, she said.

“It will be the faith community – as it always has – that will be at the people’s call when they need help and they need a helping hand. It will also be the faith community that will bring, hopefully, not only civility but a level of being open to the reality of this migration, which is a global migration.”

Casa Cornelia works with those who seek asylum in the United States because of persecution in their home countries. It also serves victims of domestic violence, as well as unaccompanied children who try to cross the border. Most are boys between the ages of 14 and 16, but Casa Cornelia has served children as young as 2 years old.

Seeking asylum

“Carlos,” who fled his native Nicaragua to avoid persecution, told the L.A. group that he was detained in a facility run by the Corrections Corporation of American (CCA), a for-profit group that runs some U.S. prisons.

“I came to save my life, and what I found was a jail,” he said, speaking through an interpreter.

In the United States, Casa Cornelia attorney Elizabeth A. Lopez explained, immigration law is administrative law, not criminal law, and undocumented migrants – even children – are not entitled to a lawyer to plead their immigration cases. A few are able to find low-cost or free legal services provided by charitable or religious organizations. Others attempt to represent themselves.

Carlos, who had no financial resources and no legal counsel, acted as his own advocate. The prison had a small, out-of-date library without Internet access, and it was there that Carlos attempted to work out a defense against being deported. He was allowed only five hours each week in the library – often cut to three.

Although he spoke no English and had no representation, Carlos was able to make his case. Although he was not granted formal asylum, he was able to remain legally in the United States. “Thank God,” he said, “the judge understood that if I returned to my country, I would die.

“With the few resources I had, I was able to prove that I had credibility and that I needed to stay in the United States.”

“Carlos represents the majority of asylum seekers and immigrants who do not have the funds to hire an attorney,” said Lopez, who added that only 3 percent of those who attempt self-representation succeed in gaining legal U.S. residency. “He is well-spoken, able to articulate his case. Most do not have his advantages.”

Lopez also mentioned that private prisons are a huge growth industry, with a strong lobbying presence in Washington, D.C. – “similar in scope to the NRA [National Rifle Association],” she said. They want immigration law to be stricter and more punitive, she said, so that they will have more prisoners in order to make more money.

Witnesses on the border

“As we move closer to the wall you will see the border patrol protecting us from the Mexican people,” the Rev. Carlos Correa Bernier of the United Church of Christ told the LACRL visitors as they traveled across the U.S.-Mexico border into Tijuana.

“Thank God,” he added, with an ironic laugh.

Correa Bernier is associate minister for border and Latino ministries for the UCC’s Southern California – Nevada Conference, and executive director of the Romero Center, (//www.theromerocenter.org/index.html) an immigration ministry located in San Ysidro, California. The Romero Center works with migrant workers on both sides of the border and offers immersion experiences for those who want to understand immigration issues better.

As the group gazed at a portion of the wall, Correa Bernier noted that such barriers are an ineffective means of border control, because if they can be built, they can be breached or avoided.

“I have seen pictures of a minivan going over the wall – they build tracks on either side of the border,” he said. “As they say, if you have a wall 50 feet high, all you need is a 51-foot ladder.

“So the policy of building walls is not working. It never worked. It’s not going to work.”

Correa Bernier outlined for the group the difficulties facing those who want to enter the United States, as well as those who have been deported.

He guided the group to an area within a mile or so of the border where they saw dozens of enormous factories called by the Mexican Spanish word “maquiladoras” meaning “bonded assembly plant.” In these windowless buildings, young Mexican women, working under male supervisors, assemble various goods that go directly to the American market.

The women, Correa Bernier said, work for a few dollars a day, six days a week. They are not permitted work breaks; their pay is docked for any time spent in a restroom or eating lunch. They are subject to losing their jobs when they turn 30, he said; the official reason is that the managers believe they are no longer able to keep up with the work, much of which is making wide-screen televisions and other electronic goods for the American market. Women are also subject to termination if they become pregnant.

Asked why the companies could not be forced to supply better wages and working conditions, Correa Bernier had a one-word answer: NAFTA.

The North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement, he explained, allows companies to exploit cheap labor in Mexico to build their goods. Any company that raises wages will have to raise its prices to compensate, and few are willing to do so in the extremely competitive U.S. markets. On paper, the companies are responsible for treating their workers well, but enforcement is very lax, Correa Bernier said.

“Our position at the Romero Center is that the U.S. doesn’t need a free trade agreement,” he said. “We need a fair trade agreement.”

He added, “People work in the maquiladoras, really, to maintain my lifestyle in the United States, because I want all my stuff to be cheap and available.

“As my father used to say, no one is guilty, and everyone is responsible.”

A member of the Los Angeles Council of Religious Leaders talks with Oscar, who grew up in the Los Angeles area but came to Mexico a year and a half ago with his parents, who were deported. The family now lives in Chilpancingo, a shantytown near Tijuana.

A town of despair

An especially emotional moment for the religious leaders was a visit to Chilpancingo, a shantytown that appears on no map, but is home to thousands of people who tried to cross the border into the U.S. illegally, or have been deported, and are now stuck there, with not enough funds to travel anywhere else. Some of them work in the maquiladoras located nearby, but jobs are generally scarce.

Chilpancingo is reached by crossing a cement-lined bed that channels the Tijuana river. Correa Bernier said he has seen the water change color from toxic chemicals released by the factories. As the group looked across the river at some 10,000 shacks built from scraps of wood and metal, they saw children playing by the polluted water. There is no school in the area, Correa Bernier said; in any case, these children would be unable to afford the fees required by public as well as private schools.

“The kids are abandoned during the day, because Mom and Dad are working,” he said. “They are exposed to drugs, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse and so on. So it’s a vicious cycle.”

A young man who lives in Chilpancingo who was walking nearby with his wife and daughter told the group that he had grown up in South-Central Los Angeles from the time he was a toddler, and had been recently deported. In fluent English, he explained that he had been sent to prison, though he denied any wrongdoing.

“I took the rap for someone else,” he said.

He is barely 24, he said. He had papers, he said, but they were taken from him and he was deported to Mexico after his prison term. His parents are still in Los Angeles, he said, with his five brothers and a sister, U.S. citizens.

He explained that the only work he has found is cockfighting. “I can’t get a job because of my tattoos and stuff. Getting a job is hard.”

“It’s hard here,” he said.

A member of the group also struck up a conversation with Oscar, a boy of about eight years, who explained that he had lived in the United States all his life, but came to Mexico with his parents when they were deported.

Speaking in English, he said that he wanted to go to school, but his mother and father had no money to send him or his siblings. He has tried to keep up his studies in the year and a half since they came to Tijuana, but he finds it difficult.

“What do you do all day?” the group member asked.

Without irony, Oscar responded that they “clean house.” He pointed out his family’s home, which like all the houses in Chilpancingo is constructed of found objects.

Would he like to return to the United States?

Yes, he said without hesitation, but not without his family. Life is hard in Chilpancingo, he said.

“It hasn’t been a good experience,” he added wistfully.

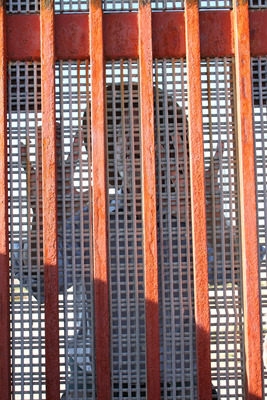

Heavy metal mesh placed over the grid of the wall in “Friendship Park” prevents all physical contact and most visual contact between the U.S. and Mexican sides of the border. Some 50 feet away on the U.S. side is a second fence that is opened only for brief periods on weekends to allow those on either side of the wall to talk to their families and friends.

House of the Poor

The LACRL group stopped at Casa de Las Pobres – the House of the Poor – a ministry run by four Roman Catholic nuns who provide food, assistance and medical care for the poor of Tijuana, many of whom are migrants. They once provided three meals a day, but have been forced by economics to cut back to breakfast only. They also supply bags of food, much of it donated by grocery stores in San Diego.

Correa Bernier, who has had a longtime working relationship with the Las Pobres, told a story of visiting the facility, where he encountered one of the sisters, who was frantic because they were ready to serve a meal, but had no tortillas (a major staple of life in Mexico). Correa Bernier showed them what he had brought them; a truckload of donated tortillas.

Correa Bernier interpreted as one of the sisters told the group that the ministry gets “only small support” from the church.

“Our supporters are the angels and the people that work here, and the providence of God,” she said.

The LACRL group made a final stop at what Correa Bernier calls “No-Longer-Friendship-Park.” He explained that a few years ago the wall was more open, and people could meet and touch their friends and relatives on the other side of the border. In recent years it has been blocked by a heavy interlocked mesh that prevents all direct contact.

Returning to San Diego, members of the group felt the enormity of the task of immigration reform, but were determined to work together to find ways to ease the human suffering of immigrants.

“First and foremost, we can show people that this is not an Episcopal issue, a Catholic issue, a Jewish issue, but it’s a human issue,” said Fr. Alexei Smith, who serves as interfaith and ecumenical officer for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles. “With all these faith traditions that we have represented on this trip, we can give a unified witness to the truth of what we face, what we need to do.

“I think we have to start looking at people humanely,” Smith continued. “We have to recognize that each of us is created in the image and likeness of God, and for us from a Christian point of view, in that wonderful gospel of the last judgment, Jesus quite clearly says, I was a stranger and you welcomed me; I was a stranger and you didn’t welcome me – and we know the consequences. And I think we have to live that.

“I think that the focus ought to be on getting legislation on radical immigration reform,” said Bishop Glasspool of the Diocese of Los Angeles. “One of the things that I learned again was we’re in it for the long haul. It’s not just a matter of writing a law or passing some resolutions. It’s a long process. Even as I heard hopefulness, particularly from the staff of Casa Cornelia, around the possibility of legislative action in the calendar year 2013, I hear also that it’s going to be eight years in effecting changes that are initially articulated through the law.

“Which makes it all the more urgent to pass the law as soon as possible, because it’s going to take time to change the way we do things.”