As John H. Taylor is ordained to the episcopate July 8 and prepares to become seventh bishop of the Diocese of Los Angeles upon Bishop J. Jon Bruno’s retirement, The Episcopal News takes a look back at their predecessors, the bishops who led the diocese from its beginnings as part of the Diocese of California. (A profile of Taylor is online here.)

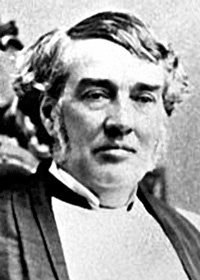

Missionary Bishop Kip blazes California trail

Missionary Bishop Kip blazes California trail

Los Angeles was the wildest of the wild west, a city almost without churches of any kind when the 1853 General Convention elected the Rev. William Ingraham Kip, rector of St. Paul’s, Albany, N.Y, as a missionary bishop of California.

A biographical sketch describes Kip as “a scholar of the old-fashioned type, an able preacher, and a man of great social gifts … He was a man of distinguished bearing, tall, handsome, aristocratic; in character a simple Christian gentleman who met with devoted courage pioneering problems.”

After his consecration on Oct. 28, 1853, Kip, with his wife and younger son, embarked on a steamer ship to the Isthmus of Panama, which they crossed on muleback; then started on another boat for San Francisco.

The refined Kip was uncomfortable in these rough surroundings, and was appalled by the behavior of his shipmates. “Altogether, I set down that scene as more like Pandemonium than anything I had ever before witnessed,” he wrote. “It was enough to convince one of the doctrine of total depravity.”

Storms wrecked the ship near San Diego, and so Kip, after narrowly escaping death at sea, first set foot on California soil in the future Diocese of Los Angeles. Later, when he made his first episcopal visit to the southern part of his diocese, Kip wrote that “it was infested by the worst class… who often rob in large parties and render it unsafe to travel.”

Homesick settlers of all faiths attended the bishop’s first service in Los Angeles in 1855, as there had been no English-language celebration in the city for six months. The bishop then traveled to Fort Tejon in an army ambulance with an escort of soldiers, for fear of grizzly bears and bandits. He went back to San Francisco, and did not return to Los Angeles for eight years.

Concerned about the lack of priests to serve in the area, Kip wrote, “Yet to how many of our energetic young men this should present a noble field! Here they would be the first heralds of the Church… (and) they might make a home in one of the healthiest places in the world.”

Kip had a strong sense of his status as a trailblazer in California. “When (those who follow us) are worshipping in splendid buildings and members of powerful parishes, how will they regard our early struggles?” he wrote. “With us the contest is a hard one, as we strive in an unsettled state of society to inculcate a regard for the things which are ‘unseen and eternal’ on a people given up to the greed of gold.”

By the time Kip died on April 7, 1893, at age 82, about 30 established congregations served Southern California. William Ford Nichols succeeded Kip as Bishop of California, and two years later, the Diocese of Los Angeles was created by act of the 1895 General Convention.

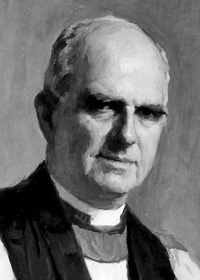

Diocese launched with Johnson’s vision, vigor

Diocese launched with Johnson’s vision, vigor

In the year 1895, two months after General Convention created the Diocese of Los Angeles, delegates arrived at St. Paul’s Church on Dec. 3 for the first Diocesan Convention. The major business was choosing a bishop.

From a slate of six nominees, the delegates elected the Rev. Joseph Horsfall Johnson, rector of Christ Church, Detroit, on the first ballot.

The future bishop was born in Schenectady, N.Y., on June 7, 1847, and was confirmed at St. Paul’s Church, Albany, where California’s Bishop William Kip was rector before his election. He attended Williams College and General Theological Seminary in New York, and was ordained in 1873. He served two churches in New York before being called to Detroit.

Johnson and his wife, Isabel, had one son, Reginald Davis Johnson, who became an architect and designer of several churches in the Diocese of Los Angeles including St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Johnson had declined an earlier election as Bishop of Marquette and also a call from historic St. John’s (the “Church of the Presidents”) in Washington, D.C. But when the call came from Los Angeles in 1895, he accepted the challenge to begin a new diocese. He was consecrated at Christ Church before leaving for Los Angeles.

On his arrival he found a diocese of about 8,000 baptized members, 16 parishes, 27 organized missions, and 31 active clergy.

The new bishop encouraged the use of lay readers in areas not served by clergy, and appointed a General Missionary to oversee “home churches” where no missions had yet been founded. He began an active search for candidates for the priesthood. One of his early recruits was a youngster named Robert Burton Gooden, later to become suffragan bishop of the diocese.

Soon after his arrival Johnson founded a newspaper to serve the enormous diocese, The Churchman and Church Messenger of Southern California (later shortened to The Los Angeles Churchman and afterwards changed to The Los Angeles Edition of Forth).

The bishop was greatly concerned during his early episcopate with the non-Christian atmosphere of Los Angeles, which he blamed on the absence of religious education in the home and on inadequate Sunday school programs. He saw the traditions of the Church as an important part of making the Gospel believable. In his convention address of 1907 he wrote, “One cannot account for such a stupendous system except as each generation of the Church believed that the communion… had been handed down to it from Jesus… Take out of the system the Ministry of Apostolic Succession and the Sacraments and, while you have a beautiful message left, still it lacks a certain backing and, sooner or later, it is bound to suffer the fate of all the messages men have received.”

Johnson helped to found many of the diocese’s still-existing parishes and institutions. He secured a new site for the small hospital established by an Episcopal nun, put it under diocesan sponsorship, enlarged it, and renamed it “Hospital of the Good Samaritan.”

The Neighborhood Settlement (now the Neighborhood Youth Association) and the Episcopal City Mission Society (now St. Barnabas Senior Services) were founded during Johnson’s tenure. Dedicated women established the Seaman’s Church Institute, the Church Home for Children (now Hillsides), and Home for the Aged (now Episcopal Communities and Services) with his support.

Johnson’s interest in education resulted in the establishment of the Bishop’s School for Girls, La Jolla; Harvard School for Boys, Studio City (now Harvard-Westlake, a coeducational school); and the Bishop Johnson School of Nursing at Good Samaritan Hospital. The Bishop’s Guild, which supports seminarians, was also launched during his tenure.

The bishop helped black Episcopalians establish St. Philip’s Church, Los Angles; supported Japanese Episcopalians who founded St. Mary’s on Mariposa Avenue in Los Angeles; and assisted Hispanic Episcopalians in starting Holy Family Church in North Hollywood.

In 1919 Johnson called for the election of a bishop coadjutor to assist and eventually succeed him. Ill-health kept him from being very active in diocesan work from mid-1926, although he did raise about $1 million in 1927 to build a new facility for Good Samaritan Hospital.

“Not bad for an old man most of you had put on the shelf,” he joked during a surprise visit to a diocesan clericus meeting shortly before his death.

Johnson died of pneumonia on May 16, 1928, and was buried in the San Gabriel Cemetery, which adjoins the Church of Our Saviour. His wife died in 1940, and was buried at his side.

Stevens leaves mark as scholar, outdoorsman

Stevens leaves mark as scholar, outdoorsman

The second bishop of Los Angeles, William Bertrand Stevens, was born in Lewiston, Maine, Nov. 19, 1884.

He attended Bates College, and, after several years as a businessman, entered Cambridge Theological School, graduating in 1910. He first served as a curate at Holy Trinity Church, New York City, for two years, during which time he earned a master’s degree from Columbia University. During his next cure, at St. Anne’s Church in the Bronx, he earned a doctorate from New York University.

Stevens married Violet H. Bond, and they had four daughters, one of whom, the late Rev. Emily Stevens Hall, later was ordained a priest of the Diocese of Los Angeles.

When Bishop Joseph H. Johnson of Los Angeles called for the election of a coadjutor in 1919, the diocese’s first choice was the dean of the General Theological Seminary in New York City. The dean declined “due to the critical state of theological education.” At a second convention in 1920, delegates elected Stevens.

Stevens’ consecration on Oct. 12, 1920 was the first to take place in St. Paul’s ProCathedral. He was 35 years old, the youngest bishop in the Episcopal Church.

As coadjutor, Stevens was in charge of parishes, missions and expansion in the post-World War I boom of the 1920s, and he continued to take special care for new congregations after he became diocesan bishop in 1928. Many of the churches built during his episcopate reflect his expertise and interest in religious architecture and art.

Although depression followed the boom period and war followed depression, the diocese grew rapidly. During Stevens’ episcopate, about 27 of the still-active missions and parishes of the diocese were established. Many of these were in the city, reflecting Los Angeles’ fast growth, but others were in the new suburbs that began to surround the urban center.

All of this work was carried out by a minimal diocesan staff: the bishop, his secretary, Catheryn Davis (who had served under Bishop Johnson, and was to continue under Bishop Eric Bloy to complete a total 42-year career), and later by the Rt. Rev. Robert Gooden, who was consecrated as bishop suffragan on May 27, 1930.

Stevens worried about the plight of his people during the Depression, and voluntarily took a large cut in his salary. In 1932 he undertook an unprecedented “Bishop’s Pilgrimage of Prayer” throughout the diocese — “an attempt, I think, to put heart into the depressed society,” his daughter Emily Hall later said.

The bishop visited every parish, mission and institution in the diocese on his pilgrimage, and people at each stop would crowd into cars to travel on to the next. “Thus a sort of chain was woven throughout the entire diocese of worship, singing and preaching,” said Hall.”

As his academic credentials show, Stevens had immense respect for education. He was a trustee of Scripps College, Occidental College, Harvard School, and the Bishop’s School. He also continued Bishop Johnson’s tradition of the diocesan Summer School, open to both clergy and laypersons. Stevens’ reputation as a scholar brought him honorary doctorates from the University of California in 1921 and his alma mater, Bates College, in 1922.

According to Hall, Stevens was especially concerned with the education and ministry of women. He encouraged women from the diocese to attend St. Margaret’s House in Berkeley, where they received a lay theological education almost equal to that for Holy Orders. Hall was often asked what her father would have thought of women in the priesthood. “I think he’d have been all for it,” she replied.

A lover of the outdoors, camping and hiking, Stevens established a camping program for the diocese. When a camp was purchased in Julian after the bishop’s death, it was named Camp Stevens in his honor.

Although dignified in worship, Stevens was known for his sense of humor and penchant for fun. He delighted in the Summer School clergy-versus-lay softball games (he usually pitched) and in the “Nut Band” of wildly-costumed priests. He played piano and flute and had a large collection of instruments, from ocarinas and tin whistles to modern flutes.

“The bishop was a very forward-looking man,” Hall said. “He would have been fascinated by computers and chips and moog synthesizers, and probably professional football.”

On Aug. 22, 1947, at age 63, Stevens died unexpectedly from complications of surgery at Good Samaritan Hospital, bringing to a close 19 years as Bishop of Los Angeles. Like Johnson, Stevens was buried in the cemetery adjoining Church of Our Saviour, San Gabriel.

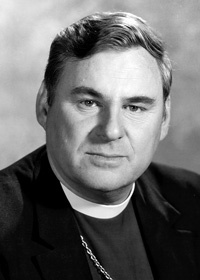

Bloy guides growth of ‘50s, channels tensions of ‘60s

Bloy guides growth of ‘50s, channels tensions of ‘60s

A third-generation Anglican clergyman, Francis Eric Bloy was born Dec. 17, 1904, in Birchington, England. His family moved to the United States when Eric was seven years old.

Bloy attended the University of Arizona, then transferred to the University of Missouri. Determined at first to break the family clerical tradition, he planned to become a diplomat after graduation, and entered the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. After a religious experience, he decided instead to seek holy orders and began his studies at Virginia Theological Seminary, graduating in 1929.

Shortly after marrying Frances Forbes Cox, Bloy began his ministry in Maryland. In 1933, he and his wife moved to California, and Bloy became curate to his father, the rector of St. James by-the-Sea, La Jolla, and later succeeded him. In 1937, the younger Bloy was called as dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Los Angeles.

Bloy was elected bishop on Jan. 28, 1948, after Stevens died in office. After his consecration in April he became, like Stevens, the youngest bishop in the Episcopal Church, a distinction he held for several years.

“Bishop Bloy entered on his episcopate at a time of great difficulty due to the great influx of people into the diocese and the rise of new communities in almost every direction,” retired Suffragan Bishop Robert Gooden wrote in 1953. “He approached this task with valor, wisdom, vision, statesmanship, true devotion, and a living faith.”

During Bloy’s tenure, about 40 of the existing parishes and missions of the present Diocese of Los Angeles were founded. The bishop took an active role in the fund drives that financed this burst of mission activity. For one of the campaigns, he appeared in a filmstrip, “The Bishop and the Genie,” in which he travelled the diocese accompanied by a cartoon genie (created by Bill Hanna of Hanna-Barbera, voice by comedian Stan Freberg) to show the need for increased mission in ethnic communities and in less-populated areas of the diocese.

“What stands out in my memory,” Bloy recalled in a 1988 interview, “was the rapid growth in Los Angeles, and the various ethnic groups that came into Southern California. I was very pleased with the general outreach of the parishes and their concern about the problems that faced us as a growing community.”

It was also in Bloy’s era that the former Diocesan House on West Fourth Stree, Los Angeles, was built, the offices moving there from the cathedral in 1963. During the latter part of his episcopate he helped engineer the division of the diocese to form the Diocese of San Diego.

As the growth of the 1950s gave way to the turmoil of the ‘60s, the nation and state faced the Cold War, the Civil Rights movements, assassinations, and the Vietnam war. Meanwhile, the national and local church dealt with the movement toward unification of denominations, liturgical renewal, and the expanding role of women in church leadership. Although these and other issues were hotly debated in editorials and Letters to the Editor columns in The Episcopal Review, Bloy commented that he did not consider these matters to be real problems because of the general good will of the clergy and people of the diocese.

The holder of several honorary doctorates, Bloy was a recognized authority on Eastern religions and a distinguished amateur astronomer. He was one of a network of persons who charted star movements and reported data to observatories such as Mount Palomar.

Bloy and his wife bought a home in Flintridge to which they intended to retire. They chose the house, he said, because its location on a hill overlooking Pasadena was perfect for stargazing from his backyard observatory (less perfect later because of increasing smog and lights below). His wife, however, died less than two weeks after his official retirement on Dec. 31, 1973.

Looking back on his episcopate, Bloy commented in 1988, “I think I’ve been able to touch the lives of individuals, and after all, that’s what we’re here for. I have no feelings of wishing I could do it better or over again. I gave what I could.”

Bloy died on May 23, 1993, at age 88.

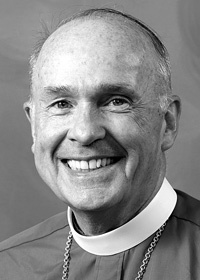

Rusack ministry links traditions, transitions

Rusack ministry links traditions, transitions

Robert Claflin Rusack, a master storyteller, often joked that he was an “in utero” Episcopalian. Born June 16, 1926, in Worcester, Mass., he was active in the church from childhood and knew early on that he would seek holy orders.

Rusack graduated from Hobart College, then from General Theological Seminary (GTS) in New York. After his ordination to the diaconate, he served at a church in Webster, Mass.

He and Janice Overfield of Salt Lake City were married in St. James’ Church there on June 26, 1951, then moved to Montana, where Rusack was ordained to the priesthood later that year. He became vicar of St. James’ Church, Deer Lodge, Mont. The Rusacks’ children, Rebecca and Geoffrey, were both born during his tenure there.

After shepherding St. James’ Church to parish status, Rusack resigned in 1955 to study for a year in Canterbury, England. Upon returning to the United States, he became rector of St. Augustine by-the-Sea, Santa Monica.

Rusack plunged into activity in his new diocese, serving on many boards and committees. He also had charge of his parish’s large day school and the parochial mission of St. Aidan, Malibu (now a parish).

When Bishop F. Eric Bloy called for the election of a suffragan in 1964 to replace the Rt. Rev. Ivol Ira Curtis (who had been chosen Bishop of Olympia), Rusack was elected on June 10.

During eight years as suffragan, Rusack served on the boards of many diocesan institutions. Deeply involved with each, he never lost his interest and concern for them over the years.

In 1970 Rusack was elected to the Board of Trustees of GTS, and later served as its president. Like the first, second and third bishops of Los Angeles, he was a trustee of Occidental College (which called him the “Bishop on Wheels of Southern California”), and from GTS.

In 1969 Rusack was elected Bishop of Dallas, but declined the election. In 1972 he was elected coadjutor of Los Angeles on the first ballot and succeeded Bloy on Jan. 1, 1974.

Throughout his episcopate Rusack called for “a balance of words and work, of witness and worship, of evangelism and social action.” He established many new ethnic ministries and during his tenure the diocese led the Church in refugee sponsorships.

It was a time of changes and controversies, chiefly concerning the adoption of a new prayer book and the ordination of women. Four congregations left the church over these matters, and the diocese was involved in a highly publicized lawsuit attempting to retain property that had been previously dedicated to the Episcopal Church. In only one case did the diocese prevail.

In 1979 Rusack faced another controversial decision: the sale and demolition of earthquake-damaged St. Paul’s Cathedral. Despite his affection for the cathedral in which he had been consecrated, the bishop felt that money from the sale would best be used for ministry. Under his leadership, the Cathedral Corp. began making grants to fund dozens of diocesan, parish and institutional programs.

Rusack died July 16, 1986 at age 60, in the midst of an episcopate for which he still had many plans. His ashes repose in the columbarium at St. Matthew’s Church, Pacific Palisades.

Borsch leads diocese with ‘Adelante’ spirit

Borsch leads diocese with ‘Adelante’ spirit

Frederick Houk Borsch, fifth bishop of the Diocese of Los Angeles, was elected in January 1988, and ordained the following June. He chose for the theme of his episcopate “Adelante,” the Spanish-language concept of “forward together.”

At the time of his election, Borsch was dean of the chapel and a professor of religion at Princeton University, where had taught since 1981. For nine years before that, he was president, dean, and professor of New Testament at the Church Divinity School of the Pacific (CDSP) in Berkeley, Calif.

Borsch worked closely with Bishop Suffragan Chester Talton, elected in 1990, on the expansion of multicultural ministries and in response to the 1992 civil disturbances in Los Angeles. One outcome was the founding of the Episcopal Community Federal Credit Union. At the time, Borsch wrote an editorial titled “Outrage and Hope in Los Angeles,” later giving the same title to a book of his collected writings. “In biblical terms,” Borsch wrote, ‘if the society fails to care for the poor, for the widows, the orphans and the strangers in their midst, that society will come to tragedy.”

From 1988 to 2000 Borsch was chair of the House of Bishops’ Theology Committee and often addressed human sexuality issues of the era. In the 1996 heresy trial in which Bishop Walter Righter was exonerated for ordaining a partnered gay man as a deacon, Borsch helped clarify the defense strategy while recusing himself from voting on the outcome. He worked with J. Jon Bruno, at that time rector of St. Athanasius’ Church in Echo Park, to build the Cathedral Center of St. Paul to serve the diocese as administrative and ministry hub.

Earlier, Borsch served for seven years on the Episcopal Church’s Executive Council, and was a member of the Anglican Consultative Council, attending ACC meetings in Nigeria and Singapore, and then co-chairing the 1998 Lambeth Conference section titled “Called to Be a Faithful Church in a Plural World.”

Frederick Borsch was born Sept. 13, 1935 in Chicago. He received his bachelor’s degree in English literature from Princeton in 1957. He attended Oxford University in England, where he earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in theology He received a bachelor’s degree in sacred theology at General Theological Seminary in New York City in 1960, and was ordained to the diaconate and priesthood that same year.

Also in 1960, Borsch married Barbara Edgley Sampson. They had three sons — Benjamin, born in 1962, and twins Matthew and Stuart, born in 1964 — and four grandchildren.

From 1960 to 1963, Borsch was curate at Grace Church, Oak Park, Ill. He then returned to England, where he taught at Queen’s College, Birmingham, and at the University of Birmingham, from which he received his doctorate in 1966.

In 1966, he was a professor of New Testament at Seabury-Western Theological Seminary in Evanston, Ill., then taught at GTS before assuming his post at Berkeley. He was granted honorary doctor of divinity degrees from Seabury-Western and GTS, and doctorates in Sacred Theology from CDSP and Berkeley Divinity School at Yale University, Conn.

Borsch — who founded Cathedral Center Press and was chairman of the board of Trinity Press International — was author and editor of some 20 books, ranging from his classic Many Things in Parables to The Spirit Searches Everything: Keeping Life’s Questions (2005) and the poetry collection Parade: Poems of Light and Dark and Light Alike (2010) and a novel, My Life for Yours. A full listing of his works and achievements is found at www.frederickborsch.com.

Borsch was a frequent guest lecturer and conference leader. His lectures and writings usually centered on New Testament issues, but he also addressed peace and justice issues, ethical concerns, spirituality and Christian poetry, theological education, contemporary church history, pastoral theology, church administration, and higher education.

After his retirement in Los Angeles in January 2002, he became interim dean of the Berkeley Divinity School at Yale and associate dean of the Yale Divinity School. He later was professor of New Testament and chair of Anglican Studies at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia.

Borsch died on April 11, 2017. Services were held at St. Martin in-the-Field, Philadelphia, and at St. Augustine’s Church, Santa Monica.

Bruno brings ‘Hands in Healing’ to diocesan, ecumenical, interfaith ministries

Bruno brings ‘Hands in Healing’ to diocesan, ecumenical, interfaith ministries

The Rt. Rev. Joseph Jon Bruno became the sixth bishop of Los Angeles on Feb. 1, 2002, the first native Angeleno to be elected to the post. He soon became a leader in the Episcopal Church in such areas as interfaith ministry, education, and initiatives of nonviolence and reconciliation.

Among the programs instituted under his leadership are Hands in Healing, a program for preventing violence; Seeds of Hope, a nutrition and wellness initiative; the Kaleidoscope Project, which facilitates ministry in multicultural settings; the diocesan Reconciliation Project, which works with people of diverse backgrounds and opinions, helping them find ways to understand each other and work together; Episcopal Housing Alliance and Economic Development; and the Interfaith Refugee & Immigration Service, a ministry that operates in conjunction with Church World Service, Episcopal Migration Ministries, and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services.

Bruno served until recently as president of the Los Angeles Council of Religious Leaders. Like his episcopal predecessors, he is a board member of the Los Angeles World Affairs Council, Good Samaritan Hospital, and other community and diocesan organizations.

Jon Bruno was born Nov. 17, 1946 in Los Angeles to Dorothy and Joseph J. Bruno. He earned a bachelor’s degree in physical education from Cal State Los Angeles and a license in criminology from Cal State Long Beach. He was a police officer in Burbank before pursuing a master’s degree at Virginia Theological Seminary in preparation for holy orders.

Bishop Rusack ordained Bruno to the deaconate and then the priesthood in 1978. From 1977 to 1979, Bruno was associate at St. Patrick’s Church in Thousand Oaks. From 1979 to 1980 he served concurrently as associate at St. Mary’s Church in Eugene, Oregon, and vicar of St. Teresa’s in Junction City. From 1980 to 1983 he was vicar of St. Matthew’s Church in Eugene. While in Oregon, Bruno was active in building church buildings and congregations.

Returning to the Diocese of Los Angeles, Bruno served from 1983 to 1986 as associate at St. Paul’s Church in Pomona. In 1986, he was elected rector of St. Athanasius’, the oldest Episcopal church in Southern California. Bishop Borsch later named him provost of the Cathedral Center, having proposed the concept for its construction in Echo Park. He also served the diocese as stewardship and development officer, and was a deputy to General Convention 2000, after serving on the security and operations staff for several previous meetings. He was elected bishop coadjutor on Nov. 13, 1999 and consecrated April 29, 2000.

Because of Bruno’s attitudes of mutual respect and understanding among people of all faiths, Hadassah of Southern California honored him for his contribution in saving the Silver Lake Jewish Community Center. In 2006, he was recognized by the Progressive Christians Uniting for his many contributions to fostering human rights and the dignity of all peoples.

At the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in 2006, he was elected to a six-year term on its Executive Council. The Virginia Theological Seminary awarded him an honorary doctorate of divinity in 2001. He has received numerous other honors, including a recent “Giant of Justice” award from CLUE (Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice).

Bruno was married to Mary Bruno in 1984. Their family includes three adult children and seven grandchildren.