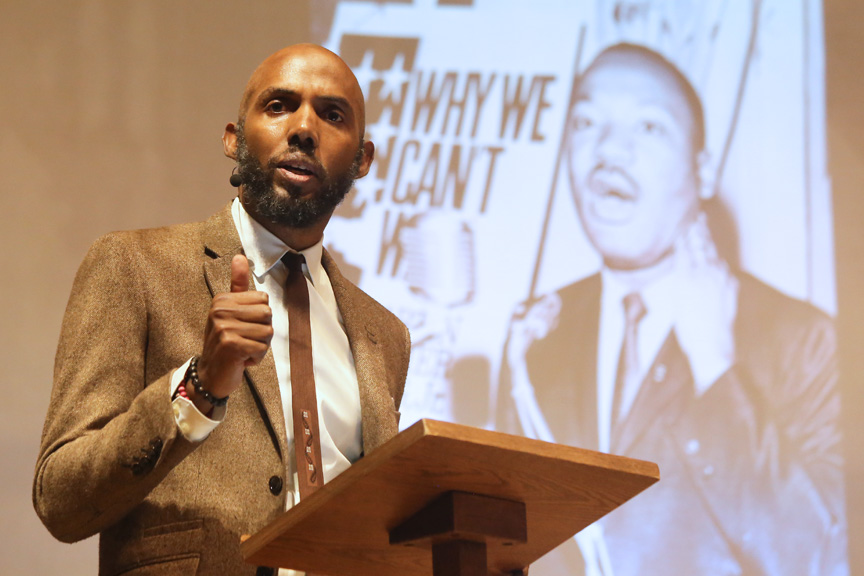

At the 2019 Martin Luther King Jr. Day event, Devon Carbado evokes King’s vision as he traces the history of racial law and its effect on the lives of African Americans.

Especially in the area of civil rights and racial justice, “law and morality are not the same thing,” Devon Carbado, a law professor at UCLA, told some 250 people at the diocesan Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration, held Jan. 20 at All Saints Church, Pasadena.

Furthermore, he said, “The civil rights trajectory, the pathway to social change, is not linear. It reflects what we might call a reform entrenchment; a movement forward, then a movement backward.”

Drawing on the legacy and writings of Dr. King and on his expertise in constitutional law and critical race theory, Carbado described a series of historical court cases in which the rights of African-Americans and other groups were either advanced or set back, and went on to link those legal precedents with challenges still faced by Black Americans today.

The Episcopal Chorale, conducted by Canon Chas Cheatham, leads the congregation in singing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” — often called the “Black national anthem.”

Readings and video comments were interspersed with hymns and anthems performed by the Episcopal Chorale or sung by the congregation in a liturgy based on classic Anglican lessons and carols services.

Bishop Diane Jardine Bruce, who also was among the event planners, and the Rev. Mike Kinman, rector of All Saints, welcomed the congregation to the service; Bishop John Harvey Taylor offered a blessing at its conclusion.

Carbado began his remarks by recognizing Martin Luther King’s towering legacy in the struggle for civil rights. “How can I hope to evidence King’s audacious optimism, his utter and complete belief in our individual and collective humanity against the background of a world in which absolute inhumanity is routinely normalized as an inevitable feature of social life?” he said.

“And how can I dream in King’s vision when that vision was less of a dream and more of a moral and existential imperative, that we as individuals, we as families, we as communities, we as a nation and we as a people of the world recognize that we cannot wait for civil rights. We cannot wait for freedom, and we cannot wait for justice.”

He told the congregation that he found inspiration in a passage in King’s Letter From a Birmingham Jail:

How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others? The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I will be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I agree with St. Augustine, then, that an unjust law is no law at all.

“From King’s perspective,” Carbado said, “immoral laws should be deeply and robustly contested.”

Carbado said that his thoughts on the non-linear nature of the civil rights struggle come both from his law training and from one of King’s speeches, delivered to a Southern Christian Leadership Conference meeting, in which he said:

I must confess that the road ahead will not always be smooth. There will still be rocky places of frustration and meandering points of bewilderment. There will be inevitable setbacks here and there. There will be those moments where the buoyancy of hope will be transferred into a fatigue of despair. Our dreams will sometimes be shattered, and our ethereal hopes blasted. We may again, with tear-drenched eyes, have to stand before the bier of courageous civil rights workers whose lives have been snuffed out by the dastardly acts of bloodthirsty mobs. Difficult and painful as it is, we must walk on the days ahead with the audacious faith in the future.

To discuss these two insights, Carbado told the congregations, “I’m going to take you to law school a little bit.”

He began with a brief survey of slave law, specifically the Dred Scott v. Sandford case, infamous for having established in American law the notion that Africans are an inherently inferior race. He read from the decision, widely considered the United States Supreme Court’s worst failure:

They [Africans] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.

Carbado described another case, Hudgins v. Wright, in which three enslaved women argued that they were indigenous — that is, Native American — and therefore should be free. The court decision, Carbado said, asserted that Africans have particular physical characteristics, including “a wooly head of hair.”

“So whether you’re on the legal side of slavery or the slavery side of slavery is going to turn on hair,” Carbado said.

“The court is in the process of litigating race … to be assigned a racial body that is situated under a system of racial hierarchy … so much is at stake with respect to how these people are defined.”

He also discussed a case in which a white man was convicted on the testimony of a Chinese witness, but appealed on the grounds that his accuser was not white and therefore had no standing. The relevant law, Carbado said, included four non-white racial categories: Indian, Negro, Black and Mulatto. The conviction was overturned on what Carbado called one of his favorite arguments in all of case law: that Christopher Columbus, when he arrived in the Americas, thought he was in Asia, and therefore called the natives Indians. The court reasoned that the people in Asia are Indians, therefore the Chinese are Indians.

“And just in case you’re not persuaded by that argument, try this one,” Carbado went on. “‘Chinese people are black.’ Why are Chinese people black? Because they’re not white! So those two arguments the court rehearses to justify the system of racial hierarchy. And the point is clear — it has to justify the system.”

Civil rights cases began with the post-Civil War Reconstruction, Carbado continued, during which time Congress and the states passed the 13th Amendment (abolishing slavery), the 14th Amendment (granting citizenship to all those born in the United States) and the 15th Amendment (establishing the right to vote), among other civil rights laws.

However, Carbado said, a law outlawing discrimination against African-Americans in public accommodations was challenged in the courts. The law, he said, was “a very modest move. It’s not radical in any sense. And the court says this is unconstitutional legislation because the Constitution does not speak to private discrimination. Individuals are free to discriminate in private on the basis of race. The constitution has nothing to say about that. This is after Reconstruction. We’re trying to turn a page. We’re trying to stay on the right side of racial justice. And already you see what I’m calling a re-entrenchment — a big step backward.”

Another legal step back, he said, was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which launched the Jim Crow era of segregation. “It was a case in which black people are saying ‘separate but equal’ violates our equal protection rights,’ and the courts said ‘no, it doesn’t,’” Carbado said. The courts, he added, essentially said: “Why? Because black people are being separated from white people, and white people are being separated from black people?” After all, Carbado said mockingly, white people don’t feel stigmatized. “If you feel stigmatized by this law, black people, it’s on you. You are imposing racial stigma on yourself, but the law is not stigmatizing you.”

Carbado summed up the history of the struggle for civil rights and racial justice as a series of “days”:

- Slavery: a regime of violence, inhumanity and legality;

- Reconstruction: The institution of slavery was abolished, but there was no redistribution of wealth, and the former slaves were simply cast adrift. “All we do is say ‘slavery was wrong,’ Carbado said. “That’s an important move, but it’s not enough.”

- Jim Crow: Also a time of violence, inhumanity and legality.

- Brown vs. Board of Education: “Brown is a significant case,” Carbado said. “It says that segregation is unconstitutional and it says that we are prepared now to say that loudly and clearly.” But, he adds, there still is no redistribution of wealth.

- Resistance: Pushback against civil rights in the South, in the North, “in the courts, in chambers of commerce, in your neighborhoods, on your school boards; resistance, resistance, resistance.”

- Blame the victim: “This is the day that we hear, ‘Why don’t they go to school? … Why don’t they stay in school? Why are they killing each other? Why don’t they get jobs? … Why don’t they get off welfare? Why are they always complaining? Why don’t they stop playing the race card? Why do they get racial preferences?’”

Carbado emphasized once again that none of these ‘days’ was followed by any kind of wealth distribution.

He concluded with an illustration of the crushing effect of systemic racism and inequality. He showed a picture of a group of sick cows. One might be inclined, he said, to blame the cows: “We say the cows are sick because they are not grazing properly, they’re not drinking enough water, they’re not pulling themselves up by their bootstraps — in other words, blaming the cows.” Or, he said, “maybe the farmer is a cowcist. Like a racist, you know.”

The congregation’s chuckles at that comment stopped abruptly when Carbado revealed the background of the picture, which showed factories spewing pollution into the air.

“You see toxicity, you see environmental degradation, and you understand that the cows are going to be sick,” Carbado said. “So it’s not like the cows pulling themselves up by their bootstraps … It’s not just about the farmer being a cowcist — they’re going to be sick.” The broader background of injustice and delayed progress, he suggested, needs to be remedied at every level.

“I surmise that King thought about this, said Carbado, quoting a lesser-known passage of King’s famous “I have a dream” speech:

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir … Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

Carbado concluded: “So when we think of King, it seems to me, we belittle him, and we belittle his legacy, when all we do is speak of “I have a dream.” We need to think in terms of Dr. King’s radical vision: a vision of love, a vision of peace and a vision of community, to be sure; but also and crucially, a vision of a accountability, a vision of reckoning, and a vision of social transformation.”