Note to readers… An upcoming opportunity to hear the David John Falconer Memorial Organ and the Choir of St. James is the Advent Procession of Lessons and Carols in the style of King’s College, Cambridge, 4:30 p.m. on Sunday, Dec. 11, St. James’ Church, 3903 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles. More information here.

Australian virtuoso David Drury played the Nov. 13 recital marking the 100th anniversary of the beginnings of the David John Falconer Memorial Organ. In the course of the program, Drury observed that the passing of time – especially centuries – is also a blending of journeys.

“There is a journey for this church, for this organ, for you and for me, as well,” said Drury, whose recital was his third at St. James’ Church. His first was in 1995 for the reconfigured organ’s All Saints Sunday debut, and the second was in 2005 marking the addition of the gallery Antiphonal Positiv Organ.

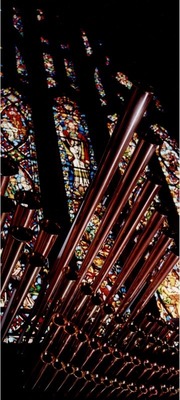

By this time the full organ also featured a gallery division of trompettes en chamade added in 2000, and more than 5,000 pipes, 90 ranks and four electronic voices. At the center of the instrument remained the re-voiced 1911 Murray Harris pipe work that survived potential scrapping in both 1923 and 1980 after serving L.A.’s first two cathedral churches.

Carol Foster, who served St. Paul’s Cathedral as its final organist-choirmaster in the years 1976-80, was part of the team that preserved the original pipe work. In a recent interview, she called today’s expanded instrument at St. James’ “one of the finest organs found in a church in Southern California.”

Los Angeles Bishop J. Jon Bruno, who is also provost of the cathedral’s continuing congregation, shares Foster’s view. “One of the things I especially appreciate about St. James’ Church and its fine music program is the teaching that happens there on a regular basis. The organ is part of that formative influence on young lives in particular.”

For the centennial recital, Drury chose Franz Liszt’s massive Fantasy and Fugue on the chorale “Ad nos, ad salutarem undam” (roughly translated “come to us, come waves of salvation”), having also played the piece a month earlier in a Sydney tribute to the composer’s 200th birthday. At St. James’, Drury – who is music director at the University of Sydney’s St. Paul’s College – traced the continuum from 1811 to 1911 to 2011 and beyond as a fitting lens for the occasion.

In such masterworks, like any journey in life, “there are themes that present themselves to us as individuals and groups, in both good times and trials,” said Drury, mindful of the recurring refrain of resilience that has marked the history of the organ and both parishes it has served.

Indeed, St. James’ Church is marking its own centennial having grown into multicultural community with a thriving K-6 school, whose campus is located at a crossroads of Wilshire Center, Koreatown and Hancock Park. This past summer’s renovation of St. James’ 1926 sanctuary — including removal of linoleum, the addition of a new terrazzo floor, and the refinishing of all pews – have made the sanctuary more visually brilliant and more acoustically “live” for liturgical and concert offerings.

Meanwhile, St. Paul’s – which has continued since 1994 as the Cathedral Center of St. Paul in Echo Park – will in 2014 mark 150 years of parish ministry dating from 1864 as Southern California’s oldest continuing Episcopal congregation. The Cathedral Center’s focus is service to the community with its credit union, weekly food program, book store and retreat rooms, while the landmark St. John’s ProCathedral, so designated in 2008, hosts various large diocesan liturgies in its 800-seat church on West Adams Boulevard near Figueroa.

Distinguished as an award-winning “improvisateur,” Drury capped his recital with a spontaneous interpretation of a theme based on the notes “spelling” FALCONER, suggested by St. James’ current music director James Buonemani to honor the memory of the organ’s namesake and devoted advocate. Falconer’s life partner, the Rev. David Charles Walker – himself the composer of the 1982 Hymnal’s “General Seminary” hymn tune, among other pieces – was present for the recital and praised Drury’s improvisation.

Falconer was St. James’ beloved parish choirmaster and day school music teacher when he was slain April 21, 1994, in a robbery outside a Los Feliz store one night following a rehearsal at St. James’. Later that week, Shawn Hubler wrote in the Los Angeles Times:

“To the hundreds of people who mourned Falconer this week, the 40-year-old organist and choirmaster with the graying beard and imposing height was as extraordinary as the cause of his death was needless.

“Here was a teacher who could inspire an inner-city 12-year-old with the soaring trumpet fanfares of Telemann and Bach. His elementary school pupils — all 330 of them — could listen to a bit of a tune and not only tell you that it sounded like Schubert but then go on to tell you why.

“So dedicated was he to his job as church organist that he almost single-handedly raised the $750,000 now being spent to restore St. James’ historic Murray Harris pipe organ. So popular was he as the parish’s choirmaster that 75 children a year at the St. James school gave up recesses just to sing for him.

” ‘That a man like this should get cut down in the prime of life is so hard to believe,’ said the Rev. Kirk Smith, St. James’ pastor.

“Noted 12-year-old Eddie Thayer, a sixth-grader at the St. James school: ‘When he died, a part of the school went with him.'”

Falconer became choirmaster at St. James’ in 1983 and early on became an advocate for the Murray Harris organ, then in storage after being removed from St. Paul’s Cathedral before the building was demolished in 1980. This loss was deeply felt by then-Bishop Robert C. Rusack, who, through the prior decade, had searched intently for means by which seismic improvements could be made and the building retained in a sustainable manner.

Not many years before, Diocesan Convention had rejected – after a notable retired cleric’s plea — a redevelopment plan that would have blended liturgical and office space at the site, and generated significant rental revenue. And as with most downtown houses of worship at the time, the congregation had dwindled in direct proportion to suburban population growth. Dean Ev Simson and Canon Pastor Morris Samuel implemented strategies for outreach, but with limited overall impact.

But the expense of retrofitting plus a city citation of the cathedral as a public-safety threat prompted Diocesan Convention, meeting in May 1979, to approve the sale of the property, which was announced in November of that year to Mitsui Fudosan (USA) for more than $4 million. Thereafter, a 53-story office tower, now named “Figueroa at Wilshire,” was erected on the site. The cathedral congregation was relocated to the nearby All Souls’ Chapel at Good Samaritan Hospital, and sale proceeds were invested to provide the “Cathedral Without Walls” ministries, a grants program, and later to fund the construction of the Cathedral Center in Echo Park.

As The Episcopal News reported in December 1979: “An estimated $2 million was needed to bring the buildings into line with anticipated earthquake codes (the Cathedral itself had been severely damaged in the 1971 earthquake and was closed temporarily for basic repair, with certain portions remaining permanently closed); the building was one of those cited by the city as constituting serious threat to public safety in the list published in the Los Angeles Times on Nov. 25; $150,000 was needed to rebuild the organ; a completely new heating system was needed (indeed, there has been no heating in the building since March); antiquated and inadequate wiring and plumbing needed replacement.”

The 1979 Christmas Eve 10:30 p.m. service was the last in the cathedral, and the final liturgy for which the Murray Harris organ was played there. Before the buildings were demolished in 1980, furnishings and artifacts were removed and stored for future use, a process overseen by cathedral warden Randolph Kimmler. After no initial plans were announced to save the organ, Bishop Rusack accepted a proposal by cathedral organist-choirmaster Foster and organ builder Manuel Rosales, and his business partner David Dickson for storing the organ for future use.

Foster adds that Rosales and Dickson had been essential partners in keeping the organ functioning at St. Paul’s. “It was a challenge to keep the organ playing from minute to minute,” she said in a recent interview, recalling frequent mechanical “coughing and wheezing” and the need to substitute various stops. “If Manuel, David, and Kevin Gilchrist had not been in the choir, I don’t know what we have done. But we made it play.”

That accomplishment had added importance given the significance of various diocesan services at the time, said Foster, who also became an active member of the General Convention commission that created the Hymnal 1982. Among notable cathedral liturgies was the 1977 ordination service of the diocese’s first woman priest, Victoria Hatch. And just three years earlier, the organ had been played for Bishop Rusack’s 1974 enthronement, a service carried live on KNBC-4 television and captured on an LP album.

Rosales, writing in a parish history of the Falconer Memorial Organ, says, “For the decade-long period in which the Murray Harris organ was in storage, some members of the Cathedral Corporation searched for ways to dispose of the instrument. Several suggestions were considered, including donating it to a theatre, a stadium, even the Hollywood Bowl.” The ballpark in question was Dodger Stadium, Rosales later said, but the trustees eventually agreed with his recommendation that another church was the most deserving recipient.

Around this time, the vestry and staff at St. James’ had determined that its 1926 Kimball organ was “beyond reasonable restoration,” Rosales notes, and the Cathedral Corporation offered the Murray Harris to the parish at no cost beyond ongoing storage expenses. The project had the support of St. James’ rector at the time, Robert Oliver, and later his successor, Smith.

“Realizing that this instrument would meet the needs of St. James’ parish, David John Falconer, organist and choirmaster, became keenly interested in the project and obtained approval to seek funding for rebuilding it in St. James’ Church,” Rosales recalls. “He had been exploring a variety of options when he approached the Ahmanson Foundation, whose managing director, Lee Walcott invited him to submit a proposal.”

Walcott and Rosales were both honored guests for the Nov. 13 centennial recital, and each read a scripture lesson during the evensong service that preceded the program.

Anchored in the fortune created by H. F. Ahmanson & Co.’s development of Home Savings and Loan, the Ahmanson Foundation chose to fund the project, and the Schlicker Organ Co. of Buffalo, N.Y., was retained to complete the work.

“David Dickson, who knew and loved the Murray Harris organ, was at that time Schlicker’s artistic director,” Rosales notes. “Concurrent with the developing plans for the organ, St. James’ decided to improve the church’s acoustics. Eventually, all asbestos-laden fiberglass was removed from the clerestory, and the plaster on the walls was increased in thickness, with particular attention paid to the chancel surfaces.

“The Schlicker Organ Company began by constructing new slider windchests and a console; eventually, they would accomplish all of the mechanical work. Some delays occurred, including the untimely early death of David Dickson in 1991. The project was revived in 1993 when Austin Organs Inc. became principal contractor,” adds Rosales, who then collaborated with Austin Organs tonal director David A. J. Broome, on the scaling and voicing of new pipe work, and assisted “throughout the installation and tonal finishing.”

The organ was delivered to St. James’ Church in 1995, the same year in which current organist-choirmaster Buonemani joined the parish staff after a distinguished tenure at Church of the Epiphany, Washington D. C.

“When I arrived on the scene in January of 1995,” Buonemani said in a recent interview, “the organ was in its final phase of re-construction at the Austin Factory. I endeavored to learn about the potential significance of the organ prior to my accepting the job here as organist-choirmaster, and most everyone I talked with on the East Coast was unfamiliar with the work of the builder, Murray M. Harris.

“Conversations ensued with Manuel Rosales, who was overseeing the reconstruction, and he assured me that this instrument would be an extraordinary addition to the organ scene on the West Coast,” Buonemani said. (Meanwhile, in San Francisco that year, Grace Cathedral hosted a service marking the 50th anniversary of the formation of the United Nations, established in June 1945 in proceedings held both at the cathedral and nearby Fairmont Hotel, bringing the journey of Woodrow Wilson’s original League of Nations concept to another milestone; please see the first article in this series.)

“In August 1995, the organ arrived, and with each passing day a new pipe sounded and was meticulously voiced for the church’s acoustics,” Buonemani added. “I was filled with growing excitement and anticipation. At its completion in November of that year, I realized that St. James’ Church was blessed with a truly magnificent instrument, ‘buttery’ in tone, as Manuel often described its diapasons, and truly cathedral-esque in its scope.

“The following months and years have seen various enhancements and subtle refinements to it,” Buonemani said. “Today, I can say with all honesty, that playing this instrument on a regular basis is among the great joys of my life, and I have been fortunate enough to be able to invite the world’s greatest organists (nearly 100 to date) to perform upon it each season. Together, we all agree that this instrument is one of the great organs of any builder, and truly an enduring jewel among Los Angeles’ historical ‘living’ monuments.”

The David John Falconer Memorial Organ is not the city’s largest; that record is held by L.A.’s First Congregational Church, said to house the largest church pipe organ in the world. Meanwhile, the Walt Disney Concert Hall organ surely offers the region’s most unusual visual design, created by Rosales and architect Frank Gehry. And — perhaps unusual given its proximity to Hollywood — the Falconer Organ has not yet been played in a feature film, although the church interior was the location for scenes in the horror thriller End of Days and episodes of the television series “Mad Men” and “Six Feet Under.”

But the organ at St. James’ Church has drawn some attention among celebrity musicians and their production colleagues. Notably, the organ was used in recording Johnny Cash’s last album, “Ain’t No Grave.” And none other than the late King of Pop, Michael Jackson, heard the organ and asked to meet the choir during a 1997 evensong memorial — co-hosted by the parish, the diocese, and the British Consulate General Los Angeles — in honor of Princess Diana.

Looking ahead, what future horizons await the David John Falconer Memorial Organ? Says Buonemani, “As every organist knows, organs are never really ‘completed,’ but like a living organism, they ‘evolve’ and are always a work in progress.”

— Robert Williams is diocesan canon for community relations and convener of the Diocesan History Project.