Rowan Williams greets middle school students at St. Margaret’s Episcopal School, San Juan Capistrano, after preaching at their school chapel on Sept. 25. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

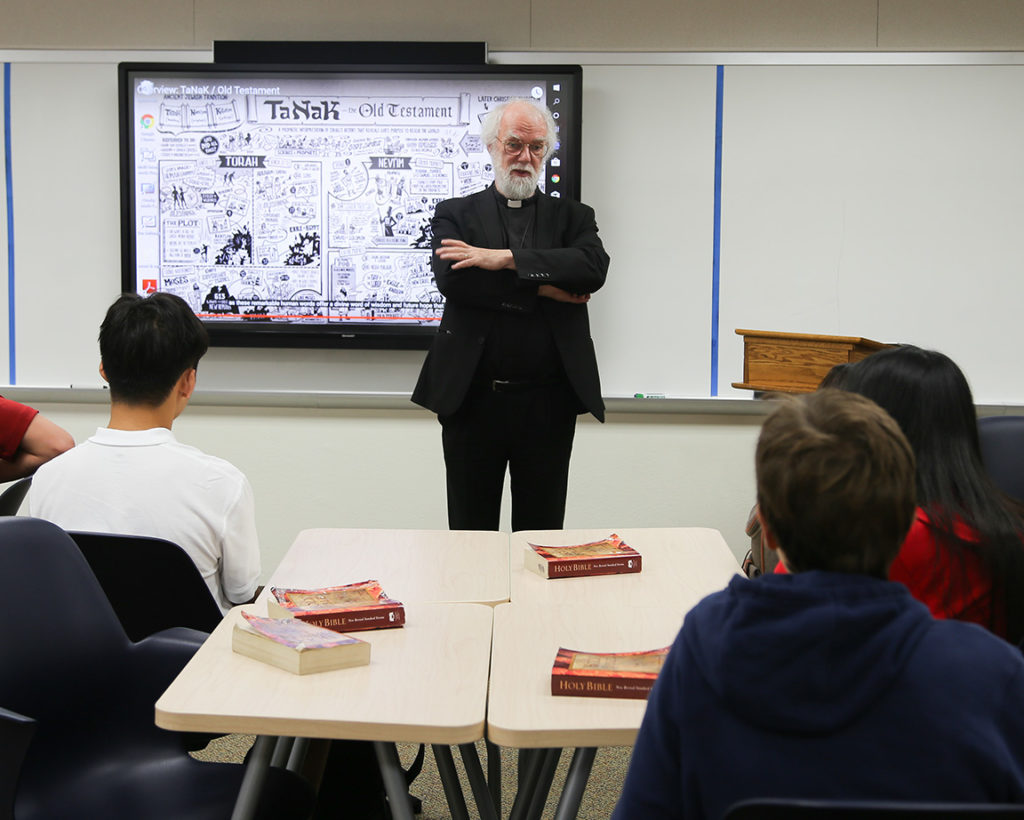

FORMER ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY Rowan Williams, visiting San Juan Capistrano and a St. Margaret of Scotland Episcopal School classroom on Sept. 25, invited students: “Anyone burning to ask a question, not about the royal wedding?”

In response, the Hebrew Bible as Literature class of ninth through twelfth graders, ages about 14 to 18, peppered him with questions, both personal and public.

Did he grow up in a religious home? Williams, who had officiated at the 2011 wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton, said he went to both Presbyterian and Anglican churches as a youth, but didn’t consider his to be a religious household.

“My parents weren’t especially religious,” he said; yet a local parish priest and mentor launched him on the path to becoming a priest, later a bishop, and eventually spiritual leader of the 85-million member worldwide Anglican Communion, simply by listening to and acknowledging him.

“He wasn’t flashy or charismatic,” recalled Williams, responding to a question about who inspired him. “He listened really hard to you and he had a real imagination of how people worked. He helped me think religious faith is a big thing, more than I could imagine.

“It’s one of the things we’re often bad at getting across to people. Most people think they know what Christians are against, but do they know what Christians are for?”

So, what did being archbishop involve? Among other responsibilities, he told the students, his role as archbishop included taking care of bishops and trying to keep all the worldwide churches talking to each other. He also consulted with Queen Elizabeth who bears the ceremonial title Supreme Governor of the Church of England.

Archbishop Williams answers questions from a class of upper school students at St. Margaret’s School, San Juan Capistrano. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

‘This Christianity stuff works’

Warm and welcoming, Williams engaged with students Emelie Miller, 16, Thomson Liu, 17 and Seychelle Balog, 16, who led a tour of the 1,250-student school campus. He also preached during a chapel service and met with school faculty and church staff.

No stranger to dealing with students, Williams, a celebrated theologian and author, is Master (or dean) and honorary professor of Contemporary Christian Thought at the 800-student Magdalene College in Cambridge. He is also a noted poet and translator of poetry; in addition to his native Welsh and English, he speaks eight other languages.

Bishop Suffragan Diane Jardine Bruce, who drove Williams to St. Margaret’s, said, “He is a kind, gentle man who loves God and loves the Anglican family.

“We spoke about our families. We spoke about his work at Magdalene College at Cambridge and the students he works with there. He was a delightful ‘carmate’ for the better part of four hours.”

Robert Edwards, St. Margaret’s rector, accompanied the archbishop during his visit. “He is a living icon,” Edwards told The Episcopal News. “He reminds us that holiness is contagious. When you are with him you feel holy.”

Williams told the bible class that his official travels sometimes led him into tense situations, like confronting former Zimbabwe President Robert Mugabe over such human rights abuses as the murder of a church worker, and the imprisonment and torture of dissenters.

Rowan Williams delivers the homily at a middle school chapel service at St. Margaret’s School. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

When Mugabe, who died at 95 on Sept. 6, 2019 in a Singapore hospital, had claimed not to know anything about the abuse, “I simply gave him a big dossier” detailing the facts, Williams told the students.

On that visit, he was accompanied by South African Archbishop Thabo Makgoba, who interceded to tell the former resistance hero-turned-autocrat, “Your behavior is shaming Africa in the eyes of the world.”

In response to a question about his most memorable travels, Williams said his role also led him to witness heartbreaking yet life-changing situations.

During a 2003 visit to the Solomon Islands, a nation of hundreds of islands in the South Pacific, he was asked to dedicate a memorial to seven members of a Christian monastic community who been murdered during “a very difficult and bloody civil war” between islands.

“That atrocity made everyone say, ‘we’ve got to stop this. If rebels are killing these holy people, we’ve got to stop.’ The entire population of the island assembled for the dedication.”

Afterwards, the island’s prime minister told Williams he was going to publicly acknowledge responsibility for the violence and atrocities and request forgiveness.

“I thought, how many political leaders would stand up in front of their people and say, ‘we were guilty, too. We got it wrong,”” Williams said. “It was one of those moments as archbishop when I thought, this Christianity stuff actually works.”

Similarly, he saw the strength of women in the Democratic Republic of Congo who reclaimed children who had been kidnapped by militias and forced to become soldiers and to perform atrocities during a bloody civil war.

“There was a group of 30 young people; about your age and up to 30 … who’d been trained to use guns, hatchets and knives,” Williams told the students. “They had killed each other, been involved in rape and terrorism, and they had all been drawn back into the mainstream life because of the church.”

At the risk of their own lives, Williams said, lay women had persuaded, even smuggled the youth out of military camps, and had helped them rebuild their lives.

“The thing was, the church was there for them. It was another moment I thought, this Christianity stuff does have traction. It allows people to take risks.”

Archbishop Rowan Williams and Bishop Diane Jardine Bruce visit a preschool classroom at St. Margaret’s School. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Sacrificing ‘your own heart, your own hopes’

Echoes of Williams’ decision to become a religious leader are heard in the Old Testament stories of Joseph, who was sold by his brothers into slavery; and of Abraham, who struggled with the sacrifice of his own son, Isaac — a story the students had just read.

It’s about conversion from being self-centered to other-centered, Williams said. That recognition that we are here to serve others also fueled his sense of call to ordination.

“I wanted to do what I could to help other people see the hopefulness or joy and consideration that comes with this, so that’s where it started. I offered myself as a candidate to be a priest.”

The biblical Joseph’s conversion occurred when he realized he received God’s gifts of influence and power, not for himself, but to save others, he said.

Similarly, “Abraham realizes what he has to give God isn’t somebody else. It’s not something you can achieve by sacrificing something else. You have to sacrifice your own heart, your own hopes.”

In moments when God seems elusive, Williams told the teens, “you have to trust … and remember how God has been with me and that I love what God has done for me. So, you sacrifice. That’s where Abraham is moving in the story. That’s why we talk of Abraham as the father of faith.”

Experiencing God, prayer

Going out in the rain can usher in a deep spiritual experience, because there is “nothing you can do about it,” Williams told the students in answer to a question about the presence of God in nature. “You have no option but to get wet. You realize, ‘I’m not necessarily the most important figure in the universe, I’m part of this big system where sometimes it rains and I get wet and the world’s not going to organize itself around me.’”

Later, while preaching at a chapel service, he told middle-school students that while archbishop he prayed daily in a crypt beneath a Lambeth Palace chapel dating to the 14th century.

Bishop Diane Jardine Bruce and Archbishop Rowan Williams get a tour of the St. Margaret’s School Camus by, from second left, sophomore Emelie Miller, junior Seychelle Balog, and senior Thomson Liu. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

“The history of the building was a bit bumpy. It had been knocked down several times, bombed during World War II, and reconstructed. The bottom half [of the wall] was smooth, but as you went further up the wall there was bare stone, big lumps of 14th-century stone jammed together.

Using the stones as metaphor, he said that just as each stone supports the one next to it, “God wants us to belong together, mostly because God knows we need one another. None of us could live for half an hour without others around.

“Each of us becomes the person we are because of the people next to us. God builds us together. These lovely bits of stone, jammed together, glued together, managed to fit together a bit untidily; each of these stones, lumpy, sharp and a bit irregular, builds the wall.”

It doesn’t mean we give up distinctive individual identity, he said; “All the things that make you feel more human; all of those are part of what you are giving to the person next to you, to make them who they are.”

He added: “For a community to work, it doesn’t have to be smooth all the time. Which means in school, church, country, the world, we don’t have to agree all the time. We just need to support one another. I can say to the person next to me, ‘I think you’re completely wrong about that, I have no idea why you say that, but I’m glad you’re there for me. I want to be there for you.’ It’s the mark of a really good community.”

When people manage to live together and support each other and value their differences, it’s a sign of God’s spirit at work, he said.

“What the world needs especially these days is a reminder that difference is vital. We don’t have to panic when confronted with people different than us. Or, if somebody else wins an argument it isn’t the end of the world. We need that strength to stick with one another, to honor one another. Each one of us is deeply different. Each one has our own strengths, all combined to keep the wall in place.”

“When you look at the person next to you, you look at somebody Jesus Christ wants in his company. You’re looking at somebody who matters colossally to God. Hang onto that because we’re in a world where pressures are at war to pull us apart.”

A few days later, in a column published in the Angelus, a newsletter for clergy, Bishop Bruce described Williams’ departure from the campus: “As we were walking towards my car the middle-schoolers were at lunch and playing on the field.As we walked by, more than 50 of them came running, wanting to shake [Archbishop Williams’] hand and thank him for visiting them and for his message.” It was, she added, a message they would never forget.

As Archbishop Rowan Williams walked by the central quad at the end of his visit to St. Margaret’s School, many students broke from their lunchtime games to shake his hand and thank him for coming. Photo: Janet Kawamoto