The Rev. Dr. John Misao Yamazaki, first vicar of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Los Angeles, joins church school teachers Mrs. Kobayashi and Miss Mabel Moorehouse beside newly acquired Dodge bus parked outside the Mariposa Avenue home used for Sunday services. Note children on porch and seated in bus. Photo courtesy of St. Mary’s Church (Mariposa), Los Angeles.

The 1918 global influenza pandemic hit Los Angeles at a time when the Sunday school of St. Mary’s Episcopal Church was growing so rapidly that the young vicar, the Rev. Dr. John Misao Yamazaki, had replaced a borrowed horse and wagon with a Dodge bus to transport the young students to the church buildings on South Mariposa Avenue near Tenth Street (now Olympic Boulevard).

A church school class of 1918 smile with the Rev. Dr. John Misao Yamazaki, vicar, and teachers outside the Mariposa Avenue home used for Sunday services by St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of St. Mary’s Church (Mariposa), Los Angeles

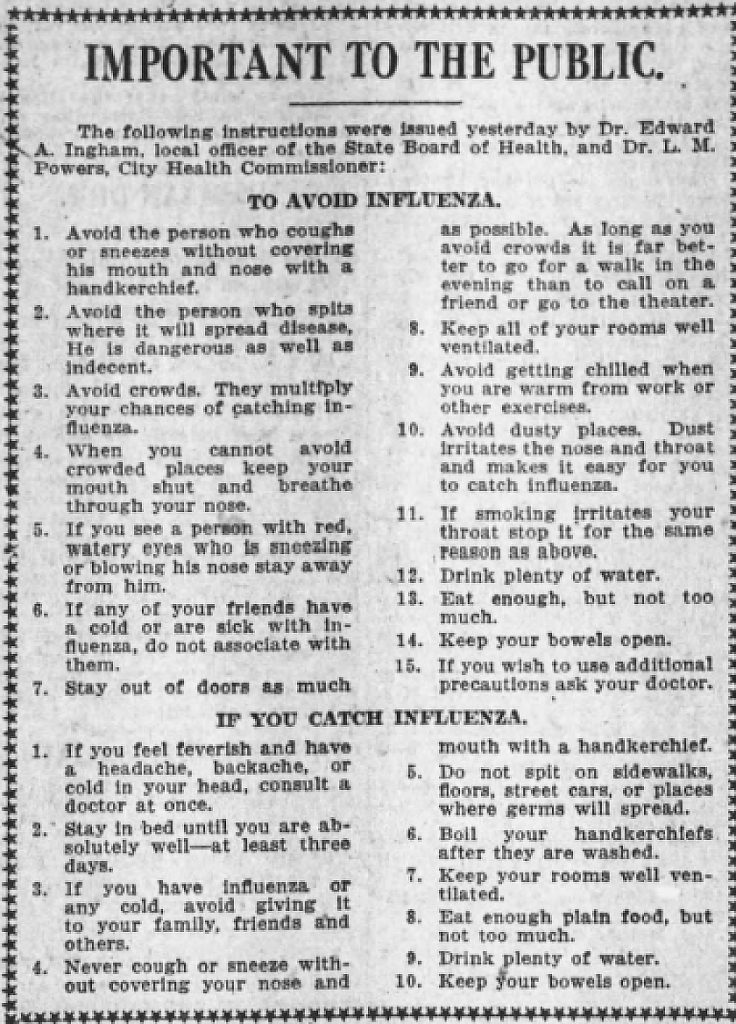

A public notice published in the Los Angeles Times Oct. 11, 1918.

But by October 11 – when the L.A. City Council and Health Commissioner Luther M. Powers closed all churches, schools, theaters and other public meeting places among efforts to stop the virus from spreading – outreach from the Japanese-speaking mission congregation was taking new forms because many “children were in bed with high fevers,” a parish historian recounts.

“Responding to urgent requests” before mandatory quarantines were enacted, “Dr. Yamazaki went to many bedsides to offer prayers,” the unnamed historian adds. “Most of the parents were non-Christians; so, for many, this was their first exposure to a Christian priest.” A number of those pastoral relationships helped build the congregation that 23 years later would weather the crisis of internment during World War II.

‘Fear not!’

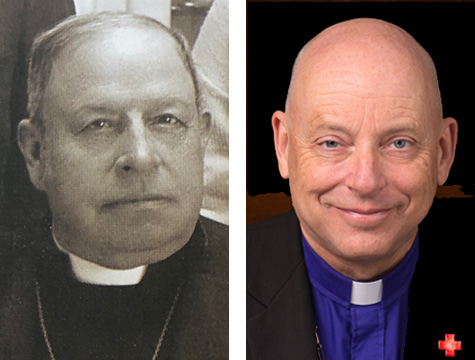

Guiding the then-eight-county Diocese of Los Angeles through the 1918 pandemic, Bishop Joseph Horsfall Johnson invoked his oft-used ministry theme: “Fear not!” Drawn from the words of Christ and angels in several scriptural passages apropos of a city and diocese named for such heralds, Johnson’s call to courage also rings true amid today’s global COVID-19 crisis that has required Southern Californians to shelter in place under mandatory order since mid-March.

At left: Joseph Horsfall Johnson, first bishop of Los Angeles. At right: John Harvey Taylor, the diocese’s seventh bishop. Johnson photo: diocesan archive. Taylor photo by Cam Sanders

Responding to the current crisis, the diocese’s seventh bishop diocesan, the Rt. Rev. John Harvey Taylor, is providing leadership that marshals technology unheard of in Johnson’s time: daily digital posts including a series of pastoral directives that began with the exhortation: “Pray hard. Stay cheerful. Follow the news and the advice of state and county health authorities when it comes to public gatherings.” Taylor’s posts link regularly to numerous online resources for ministry, finance, and technology among other aspects of crisis response (see web pages here). He, Bishop Diane Jardine Bruce, Canon to the Ordinary Melissa McCarthy, and other diocesan leaders use their Facebook accounts and other social media to share articles, tips, and reassurance while keeping pastoral relationships strong during the quarantine.

During Johnson’s 1896-1928 tenure – when party-line telephones overloaded as the 1918 pandemic spiked in the Southland – the city of Los Angeles grew from 75,000 to more than 1 million residents compared with today’s 4 million Angelenos in Southern California’s wider population of 24 million.

In other contrasts, while the current pandemic to date has claimed 78 lives to date in Los Angeles County among 6,766 nationally and 56,767 worldwide, 1918-1919 flu crisis claimed 2,713 lives in Los Angeles as part of the death toll of nearly 700,000 nationally and an estimated 50-100 million globally. More than half of those casualties were between 20 and 45 years of age, mostly young men returning from overseas military service during World War I.

Much correspondence from Johnson’s ministry, including any 1918-1919 communiques about the flu pandemic, was lost due to a fire that struck the diocesan offices around the time of the Great Depression. But the bishop’s official journal for the period predictably shows no Sunday parish visitations until Nov. 24 when he officiated at All Saints’, San Diego, which city and county was then part of the Diocese of Los Angeles. On Dec. 1, the first Sunday of Advent that year, Johnson visited Holy Faith, Inglewood, and the next day, L.A. officials lifted the flu ban, prompting the return of shoppers to downtown for pre-Christmas buying.

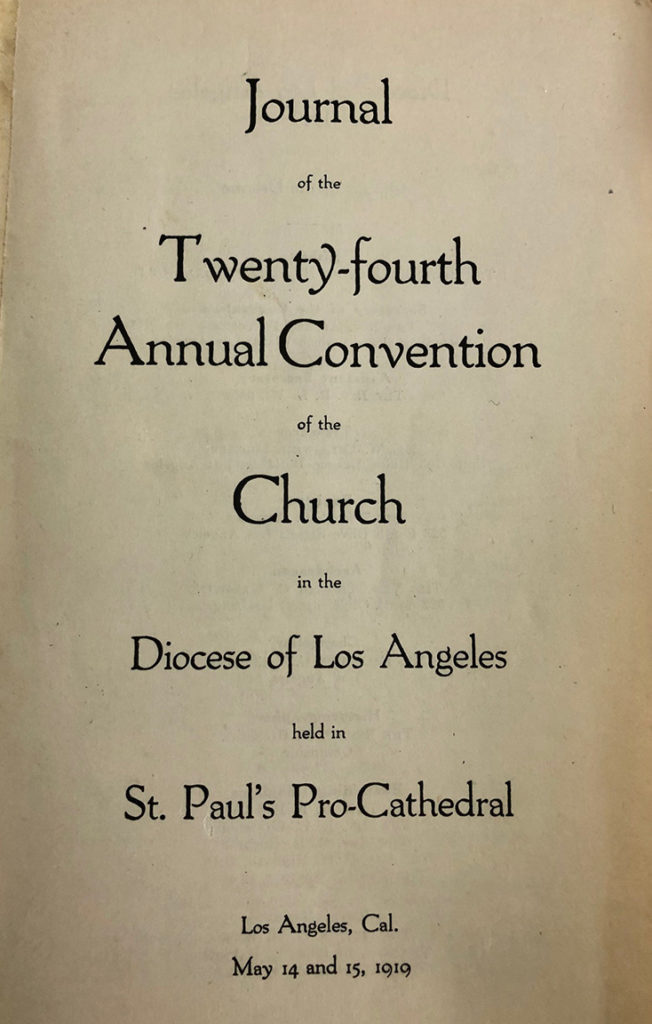

During the diocesan Standing Committee’s January 15 meeting, members formed a council of advice to the bishop, with all concurring that Diocesan Convention would defer its 24th annual meeting to May 14-15, 1919, rather than assemble during its usual January timeframe. The Rev. Robert B. Gooden, then headmaster of the Harvard School and later first bishop suffragan of the diocese, recorded and signed the minutes of that meeting.

During the diocesan Standing Committee’s January 15 meeting, members formed a council of advice to the bishop, with all concurring that Diocesan Convention would defer its 24th annual meeting to May 14-15, 1919, rather than assemble during its usual January timeframe. The Rev. Robert B. Gooden, then headmaster of the Harvard School and later first bishop suffragan of the diocese, recorded and signed the minutes of that meeting.

In his 1919 address to convention, Johnson employed his customary erudition to offer a reflective overview of events of history that had combined to occasion the recent wartime adversity including the influenza outbreak, declaring that, “the final and ultimate source of invincible power is God.” In the latter half of his address, Johnson, then in office for 23 years, called for the election of a bishop coadjutor, which followed in 1920 and launched the episcopate of 35-year-old W. Bertrand Stevens, then rector of St. Mark’s, San Antonio, Texas.

Congregations, hospital respond

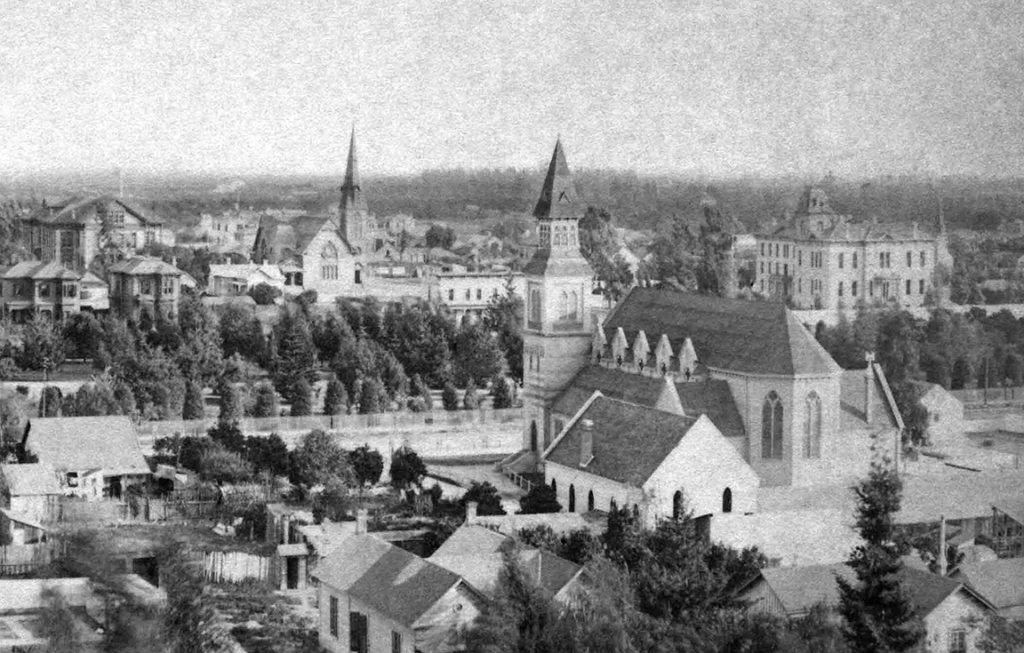

In those years, Convention assembled at St. Paul’s Pro-Cathedral, a striking carpenter gothic wooden church completed in 1883 and razed in the early 1920s to make way for the Biltmore Hotel. A week after the Nov. 11 armistice ended World War I, L.A.’s Central Park, located across Olive Street from the pro-cathedral, was named for U.S. Gen. John J. Pershing, storied commander of the Western Front.

St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral (foreground) looking out over L.A.’s Central Park, renamed Pershing Square in 1918 to honor U.S. Gen. John J. Pershing, World War I commander of the western front. Photo: Diocese of Los Angeles archives

But, due to the influenza ban regulating houses of worship in the region, Episcopalians were prevented from hosting a post-war celebration at St. Paul’s, where just the year before President Woodrow Wilson had worshiped while in Los Angeles to promote his concept of the League of Nations.

Southland denominations – except Christian Science practitioners who sued and won the right to hold meetings – complied consistently with required closures during the flu crisis. Religious leaders were among those called upon to quell misinformation and stereotyping, not unlike that marking the present crisis.

The 1918 crisis was exacerbated when “fearful people responded in unhelpful ways that were rooted in racism and xenophobia,” as Joel Klein, head of science collections at San Marino’s Huntington Library, recently told the Los Angeles Times. The Huntington, UCLA, and the City of Los Angeles hold key archives reflecting the 1918 flu pandemic and local action beginning with the first quarantines, in September, at the Naval Reserve Station at Los Angeles Harbor and the U.S. Army Balloon School in Arcadia.

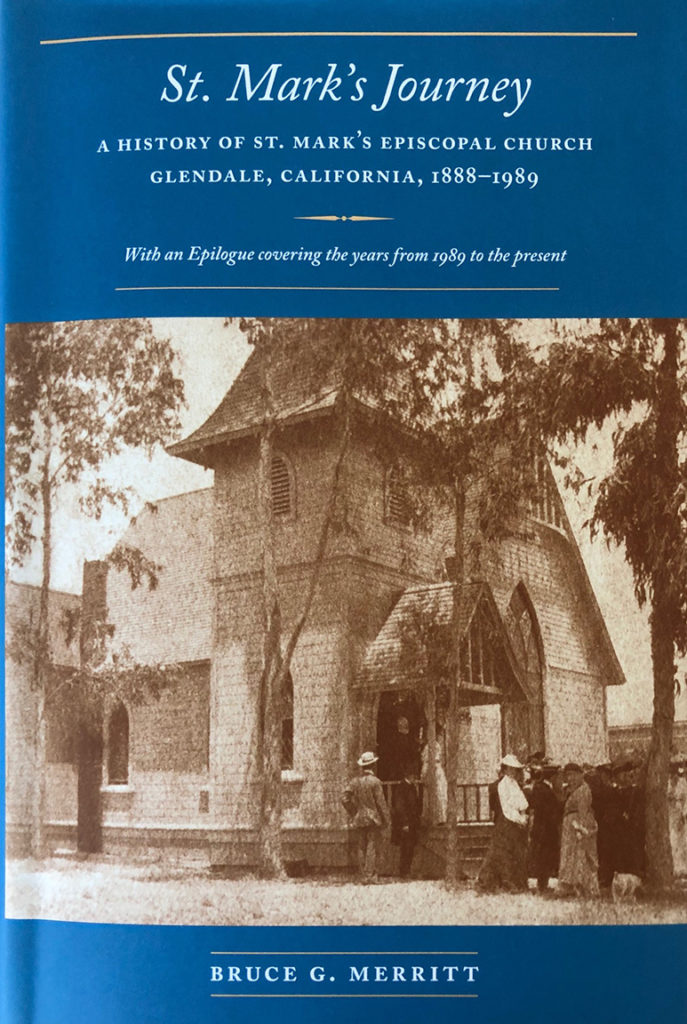

Cover of Glendale parish history by Bruce G. Merritt.

Wartime connections with the 1918 flu pandemic are reflected in the experience of a family from St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Glendale, among the oldest continuing congregations of the Diocese of Los Angeles. Glendale parishioners who knew longtime lay leaders Eleanor and John Whitaker surely were saddened to learn that their “only son, Reginald, a young engineer recently out of the army and living up in Dunsmuir, had been stricken and died,” parish historian Bruce Merritt writes in his 2013 book St. Mark’s Journey. Noting other post-war responses, Merritt reports that parishioner Helen Campbell “continued knitting army sweaters at home, and when the embargo was lifted, she quickly mobilized the Women’s Guild … to make refugee garments.”

Nearby in Pasadena, Episcopalians from All Saints Parish, Church of the Angels, and St. Mark’s Parish (now in Altadena) wore face masks in compliance with a city ordinance later overturned but presaging a similar nationwide mandate today.

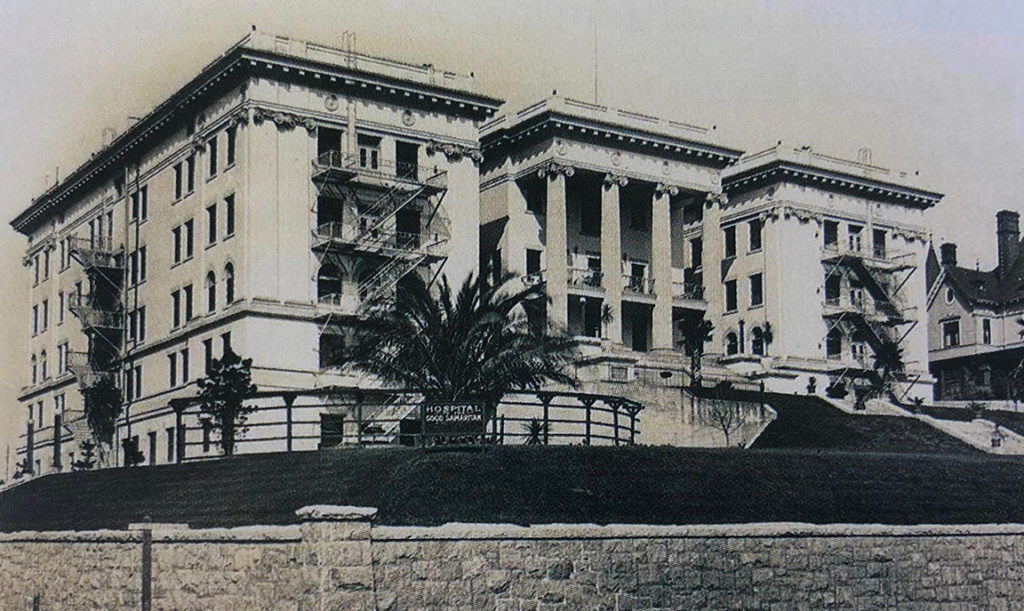

Meanwhile, L.A.’s Good Samaritan Hospital – then a diocesan institution and since 2019 a branch of the Whittier-based PIH healthcare system – did its part in responding to the crisis.

Good Samaritan Hospital, 1913 building looking northeast from Wilshire Boulevard (then Orange Street) and Witmer. Good Samaritan Hospital photo

“Hospitals could do little more than they had done in previous generations: keep the patient comfortable and wait for the illness to take its course,” writes David L. Clark in his 2010 history of Good Samaritan. “To the roll call of employees lost in the recent war, there would be added those who succumbed to the scourge. The minutes of the Nov. 13, 1918 board meeting included a note that the trustees had sent a sum of money ‘to the family of Mr. W. Drury who has been employed as a barber in the Hospital, and who recently died of influenza, leaving his family without means.”

To assist today’s congregations and institutions responding to the COVID-19 crisis, the diocese has established the “One Body & One Spirit” Emergency Appeal, to which donors may give online here.

UPDATE

(July 3, 2020) Three months after this story was filed, by July 1, 2020, Los Angeles County had attributed 3,402 deaths to COVID-19 among a reported toll of 130,103 lives lost nationally and 514,298 worldwide. Also as of July 1, L.A. County’s infection rate stood at 105,507 presumptive positive cases among 2,727,996 in the United States and 10,599,620 globally, according to national and international health organizations.

Meanwhile, for the same period, the five other counties within diocesan boundaries reported as follows:

- Orange County, 345 deaths among 14,413 confirmed positive cases;

- Riverside County northeastern region only (remainder of county is part of the Diocese of San Diego), 228 deaths among 6,856 confirmed positive cases;

- San Bernardino County, 258 deaths among 12,746 confirmed positive cases;

- Santa Barbara County, 29 deaths among 3,164 confirmed positive cases;

- Ventura County, 46 deaths among 3,096 confirmed positive cases. Within the Diocese of Los Angeles as of July 1, COVID-19 deaths totaled 4,308 among 145,782 confirmed positive cases.

— Robert Williams serves the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles as canon for common life and as historian-archivist. His great-grandmother’s first husband perished in the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Learn more here:

Los Angeles Times, March 16, 2020:

This isn’t the first time a virus caused social panic. The Spanish flu did too

Inland Valley Daily Bulletin, March 5, 2019:

‘Spanish flu’ epidemic shut down Inland Empire cities a century ago

Riverside Press Enterprise, March 26, 2020:

Before coronavirus, Spanish influenza hit Riverside County in 1918

Orange County Register, May 3, 2009:

Santa Barbara Independent, April 1, 2020:

Patheos, March 10, 2020:

St. Mark’s Journey: A History of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Glendale, California, 1888-1989, by Bruce G. Merritt (Los Angeles, Melwood Press, 2013).

A History of Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles 1885-2010: A Tradition of Caring, by David L. Clark (Los Angeles, Good Samaritan Hospital, 2010).