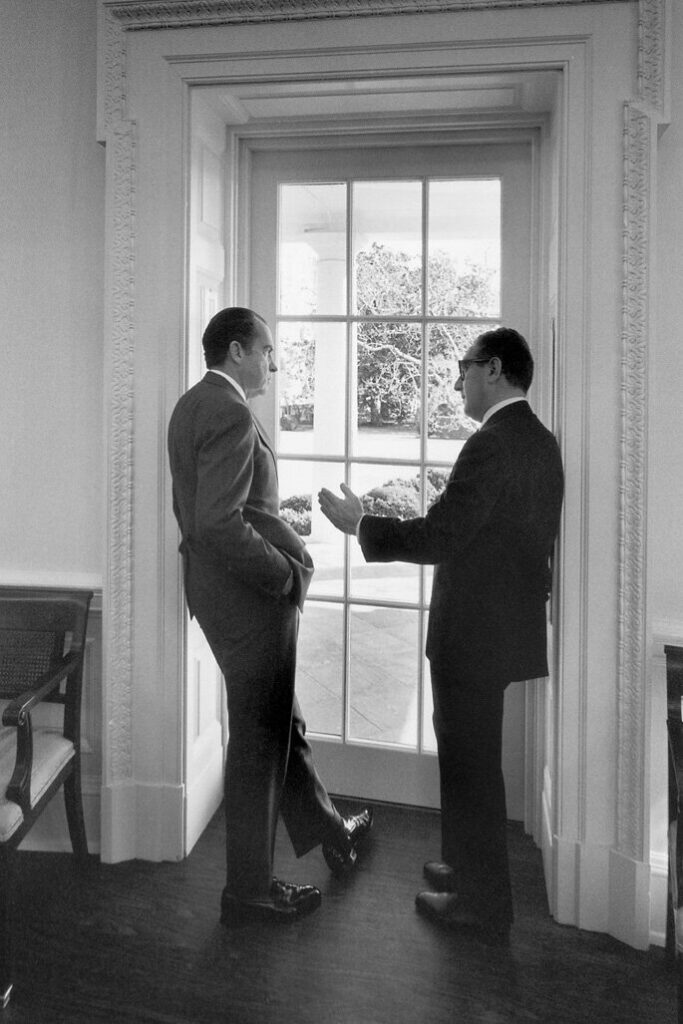

Photo: Fred J. Maroon

Negotiating with Henry Kissinger in April 1994, I understood how his North Vietnamese counterpart Lê Đức Thọ may have felt at the Paris peace talks. As director of the Nixon library, I was working on the program for 37’s funeral in Yorba Linda. The ceremony would end with a flyover by four fighter jets, which would come at a time certain. I was struggling to get Kissinger to promise to stick to eight minutes in his eulogy.

We had about 45 minutes for speeches. President Clinton and two other eulogists were coming, too, not to mention officiant Billy Graham, who’d offer a homily. I told Henry I was sure he of all people understood the necessity of precise, predictable arrangements. “Of course,” he said. “Mine will be no more than eight minutes, as you ask. In any event no more than ten. But you can count on eight, perhaps ten or 12, or maybe just a little more. Whatever you think best.”

I needn’t have worried. He spoke graciously about his friend and colleague — not a word too many. Kathy Hannigan O’Connor, 37’s last chief of staff, and I witnessed their collaboration for nearly 30 years, all after Nixon’s presidency, as they tried to polish their legacies by writing memoirs, traveling the world, and advising successors. Each naturally wanted to be remembered as prime mover in the policies that worked best. But they also wanted one another’s support against their critics. So by and large they maintained a united front.

With Kissinger’s death today at age 100, from now on, history alone will speak. Their most controversial actions — bombing Indochinese communists, tilting to Pakistan and supporting its brutal war in Bangladesh, and helping overthrow Chile’s socialist president — were what they did at the Cold War, which lasted nearly a half-century and nine presidencies and launched ten thousand dissertations. Vietnam will get the most attention. Nixon stayed for four years, while withdrawing U.S. troops, because he thought he could save South Vietnam. Kissinger didn’t agree. He just wanted to impress Moscow, at the expense of hundreds of thousands more U.S. and Vietnamese lives.

To their credit, he and Nixon were also making peace with the Soviets and China, hoping to build a structure of peace that would mean fewer proxy wars, fewer Koreas and Vietnams. But Watergate doomed Nixon’s hopes for South Vietnam, U.S.-Soviet detente, and Republican pragmatism in general.

As the Cold War reheated during the Reagan years, Nixon and Kissinger made common cause again, trying to nudge 40 closer to the center on U.S.-Soviet issues. In the mid-eighties they decided to submit a column to The New York Times supporting a treaty limiting intermediate-range nukes in Europe. Anyone else would have had an aide write it, but not these two overachievers. They sent drafts back and forth by fax until it came down to about a dozen disputed passages, which I marked with PostIt notes. The three of us sat in Nixon’s lower Manhattan office for a hour as they battled. They finally reached an impasse over whether to write “possibly” or “probably.” Kissinger looked at me and said, “What do you think?”

Their differences were even more pronounced in the spring of 1993 at a conference on the post-Cold War world that we hosted in Washington. Nixon called on the George H.W. Bush administration to do more to encourage political and economic liberalism in Boris Yeltsin’s Russia. Kissinger urged a policy of containment, arguing that Russia could be imperialist without being communist. Perhaps they were both right. Following Nixon’s advice early on could have forestalled Putinism, which vindicates Kissinger.

After Nixon died, one of our projects was reviewing his White House tapes before they were opened under an agreement I’d negotiated with the National Archives and Justice Department. Kissinger called one day and said he was afraid that he had been too agreeable when Nixon said outrageous things, especially about Jewish people such as Kissinger. I promised we’d send summaries of his portions. These were prepared by our brilliant tape whisperer, Robert Nedelkoff. Much relieved, Kissinger called again. “Over the years I’d persuaded myself I’d been far more obsequious than I actually was,” he said.

He also called me in 2009, when he heard I’d decided to resign as executive director of the Nixon foundation to work in the church full time. He was a member of our board and had stayed in spite of turmoil about the board’s autonomy a few years before that had drawn in members of President Nixon’s family. I was at a retreat in Santa Barbara with priest friends, including the Rev. Canon Greg Larkin, who reminded me about this today. “Excuse me, guys,” I said. “I have to take a call from Henry Kissinger.” Said someone at a clergy event exactly once.

When I picked up, he said, “What happened?” He believed one would have to be under duress to leave a job like mine for the church. I promised there was nothing sinister and thanked him for supporting us in our efforts to bolster the independence of the foundation board. “You’re welcome,” he said, “although I am unaware of having offered you any support.”

“You didn’t quit,” I said. And he never did. He counseled every president elected after those he’d served, Nixon and Ford. He was writing yet another book when he died. When he erred, it was because peace through the balance of power was his idol, even when the innocent — Chileans, Kurds, Bangladeshis, Vietnamese, U.S. soldiers — were lost among the shifting tectonic plates of great power interests. Some say he never got over fleeing Hitler with his family in 1938, when he was 15. Fleeing the chaos of a Europe out of balance and on the brink of global calamity.

Sure enough, in 1989, after the Tiananmen Square massacre, he went to Beijing and told Chinese leaders that no great nation could tolerate demonstrators camping out indefinitely in the heart of its capital. It could lead to chaos. Imbalance. And yet he had seemed to acquiesce in state terrorism. Reading about this, Nixon called Kathy and me in and announced his plan to go to China himself, to tell the same leaders that what they had done to innocent demonstrators was unpardonable. This was the dance they always did, Kissinger the severe realist, Nixon, if you can believe it, when he was at his best, the dreamer. And now, perhaps, it continues.