Bishop Suffragan Diane Jardine Bruce presents speaker Devon Carbado with a gift for the Critical Race Studies Program at UCLA, where he is a law professor, as Jennifer Pavia, Holy Faith’s priest in charge, looks on. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

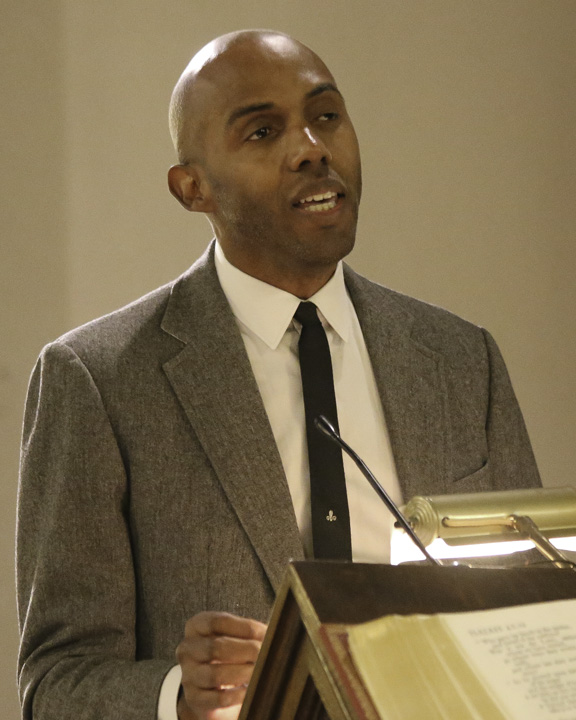

Devon Carbado delivers a meditation at the Diocese of Los Angeles’ annual Martin Luther King Day celebration, held this year at Holy Faith Church, Inglewood. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t a static figure, and he wasn’t all about “racial kumbayaism,” UCLA Professor of Law Devon Carbado told the congregation at the Diocese of Los Angeles’ annual celebration of the late civil rights leader on Jan. 18. The service at Holy Faith Church in Inglewood continued a long tradition of events in the diocese honoring King’s life and legacy.

King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech in 1963 wasn’t just about respecting racial differences, ending discrimination, and breaking bread together, Carbado said in his address, which he titled “The Three Rs of Civil Rights: Reconciliation, Reparations and Redistribution.”

“None of us is going to argue against those ideas,” he said. But, he added, that’s the easy part. Racial reconciliation of the kind needed to advance the rights of African-Americans will take hard work.

Readings, music tell story of King’s ministry, Black experience

The service, which followed a “Lessons and Carols” format, was sponsored by the Program Group on Black Ministries of the Diocese of Los Angeles. Canon Suzanne Edwards-Acton, program group chair, was among those who read from King’s writings and those of other authors. Chicana feminist poet and teaching artist Angela Aguirre also read two original works, and Presiding Bishop Michael Curry addressed the congregation in a video message. The readings were interspersed with hymns and anthems performed by the Episcopal Chorale, a renowned gospel music group directed by Canon Chas Cheatham. Bishop John Harvey Taylor, Bishop Diane Jardine Bruce and Canon to the Ordinary Melissa McCarthy also took part in the service. The Rev. Jennifer Pavia, priest-in-charge, welcomed the congregation to Holy Faith Church. Some 200 people attended the service; another 900 followed the livestream on the Diocese of Los Angeles Facebook page. The full-service video is here; a video of Carbado’s address is here.

Carbado is an associate vice chancellor at UCLA and a professor at the university’s school of law. His legal expertise includes constitutional criminal procedure, constitutional law, and critical race theory, and he is connected with UCLA’s Critical Race Studies Program, which focuses on racial justice advocacy, racial justice teaching, and racial justice law. Carbado also spoke at the 2019 MLK event; an Episcopal News story is here.

Gertrude Bradley of the Episcopal Chorale sings “His Eye is on the Sparrow” at the Martin Luther King Jr. service. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

In his address, Carbado quoted a section of the “I Have a Dream” speech that is less known, in which King talked about how the promises of the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of slavery did not deliver either freedom or equality to Black people in the United States. Carbado read the passage:

“One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. So we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

“In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note … It is obvious today that American has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, American has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

“But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

King wasn’t just calling for racial harmony and healing, Carbado said. “King was in a sense asking American society to ‘show us the money.’ King was asking for social transformation. I don’t mean that literally in the sense of dollars and cents. What I mean to say is that he was asking for investment in the material well-being of Black people’s lives.”

The Episcopal Chorale, directed by Canon Chas Cheatham, performs at the 2020 Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration at Holy Faith Church, Inglewood. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Checks that bounce, checks that are insufficient

Carbado went on to “riff,” as he put it, on King’s idea of a check. “But I want to change up the metaphor just a little bit,” he said, “to suggest that the problem for us as Black people in this country is not just that the check has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’ It’s not just that our civil rights check has repeatedly bounced, though that’s a part of the problem. It’s also that the civil rights checks that have cleared have not been enough to cover the cost of discrimination and the cost of inequality in Black people’s lives.

Poet and performance artist Angela Aguirre reads one of her poems, “EAST LA 1968” during the MLK service. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Calling upon his legal training and extensive research into the history of African-American civil rights, Carbado traced history of the “checks” that the U.S. has issued to its Black citizens to make them equal citizens with equal opportunities, and noted where those checks failed to be sufficient to the need.

“Let’s think about slavery,” he said. “We do not talk enough about slavery as a foundational dimension of American democracy. Slavery was not oppositional to American democracy. Slavery was not inconsistent with American democracy. Slavery was a form of American democracy, and we always have to remember that that’s the case.”

Black people had no rights and no property – in fact, they were property – before the Civil War, Carbado said. Reconstruction after the war brought some advances; a flurry of constitutional amendments outlawed slavery, guaranteed citizenship and gave African-Americans full voting rights.

“We cashed the Reconstruction check,” he said. “Do we get no racial inequality left over? Or are we still racially subordinated in that context?” The answer, he added, is that inequality remained.

“So we cleared the check. It’s not as though that check bounced. It was just never enough to deal with the inequality that slavery produced.”

He continued the metaphor by citing the Jim Crow era, in which Black Americans faced legalized segregation, inferior housing and schools, and denial of opportunities to vote.

But a new check, he said, was issued in the form of Brown vs. Board of Education, which overruled the earlier Plessy v. Ferguson, a notorious Supreme Court ruling that declared separate-but-equal schools, housing and other opportunities as constitutional because, Carbado said, “segregation treats Black people and white people exactly the same. You should look at me puzzled. How does the Supreme Court sustain that analysis? Well, racial segregation separates Black people from white people, and racial segregation separates white people from Black people. It’s treating them the same. This is supposed to be the highest intellect on the Supreme Court, articulating the argument.”

Brown v. Board of Education outlawed separate-but-equal schools, but still the inequality continued, Carbado said. In the Civil Rights movement of the mid-1960s African-Americans sought an end to private discrimination, state discrimination, legalized violence in the form of lynching, and voting discrimination.

“Once again, there’s a civil rights check,” Carbado continued. “The Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Voting Rights Act of 1965. We clear these checks. They do not come back bounced. There is still a racial remainder. We have still not intervened in a way that fundamentally addressed the ubiquitous racial inequality on the ground.”

The pattern continues, he said. “If we’re to think about what happened in the 1970s, in the 1980s, in the 1990s and in the present, these are moments in which we stopped getting civil rights checks. So we get checks initially that bounced, marked “insufficient funds”; then we get checks that are insufficient to the task of eradicating racial inequality; and then we stop getting checks.

“What do we get? We get a conception of discrimination that says the only form of discrimination that we’re worried about, constitutionally speaking, is intentional discrimination.”

Linda Broadous-Miles gives a stirring performance of “Precious Lord” in response to Devon Carbado’s address. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

But that definition doesn’t address the real problems of racism, Carbado said. “Racism operates more structurally. So when the constitutional law structures itself around eliminating only intentional forms of discrimination, it’s going to leave the criminal justice project in place. It’s not going to deal with all the forms of disparities that we know exist in society today. It’s not going to deal with the fact of segregation. It’s not going to deal with the fact that our schools are still ‘separate and equal.’ It’s not going to deal with our underemployment. It’s not going to deal with the extent to which we continue to suffer from an income gap. None of that is reachable if the discrimination question that you’re asking is whether some individual white person intentionally discriminated against some individual Black person. We have to do better than that.”

Social change, Carbado said, never comes about because everyone agreed it must happen. “There’s never been a moment when this nation has been ready for the kind of civil rights claim that Black people have demanded,” he said. “This is precisely what King was referring to when he suggested that there is ambivalence; when he suggested that there is vacillation; when he suggested that there is backlash; when he suggested that we get things on the installment plan at best. This is what he is speaking to. In fact, as I suggested earlier, our civil rights claims are typically framed as special rights claims; that we’re asking for preferences.”

This has been a frequent objection to civil rights legislation and favorable court decisions, dating back to the post-Civil War era, Carbado said.

“All of this is to say, I think, is that when we engage the question of King and his legacy we have to bring back some radicalism into the conversation. We have to move beyond the idea that what King was asking for was simply ‘kumbayaism.’”

Racial harmony is highly desirable, said Carbado, but King “also believed in the fierce urgency of now. He also believed that we cannot wait; that the imperative that we wait rings in the ears of every Black person who hears with piercing familiarity. King also insisted on contesting racial power. He also insisted on realism. He also insisted on effectuating social transformation. In this respect, the point is not that we should forget King’s dream. It’s rather that we should properly remember it as including a radical vision of social transformation toward what King called ‘genuine equality.’ It’s only when we think of King in these terms, it seems to me, that we might, just might, avoid the nightmare about which he was so profoundly concerned at the end of his life.”

Bishop John Harvey Taylor, right, and Professor Devon Carbado, second from right, join in a hymn at the Martin Luther King celebration at Holy Faith Church, Inglewood. Photo: Janet Kawamoto