Greg Kimura is excitedly pointing out “Hello Kitty” backpacks, toothbrushes, fanny packs, artwork, a Swarovski crystal Hello Kitty, a Sesame Street Elmo Hello Kitty, images of the twinkling-eyed character depicted in dresses for Lady Gaga and America’s Top Model Competition — even a Hello Kitty robot.

Greg Kimura talks with visitors in his office at the Japanese American National Museum, of which he is executive director. On Sundays, he serves as a priest at St. Cross Church, Hermosa Beach. Photos/Janet Kawamoto

“If you speak to it in Japanese, it’ll say things back at you,” said Kimura, an Episcopal priest assisting at St. Cross Church, Hermosa Beach. He is also the president and CEO of the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Koreatown.

“I really like this, because this is the first time something culturally Japanese American was embraced by the wider culture, seen as cool by the wider culture,” Kimura told the Episcopal News Oct. 2 behind the scenes as JANM prepared to debut the exhibit commemorating the 40th anniversary of Sanrio Corporation’s “Hello Kitty.”

“To me, it looks like a Maneki-neko,” the familiar red and white Japanese calico cat with an upraised beckoning paw — representing luck or welcome — often found in the entrances of Japanese American-owned homes and businesses, he said.

“Only, she may or may not be a cat,” chuckled Kimura. When he recently made an offhand remark during an interview that Sanrio had asked JANM not to refer to Hello Kitty as a cat but as a “she” or a little girl, the comment went viral, along with news of the Oct. 11 – April 2015 exhibit.

“It was the top trending topic on Twitter,” said Kimura. “Two days later, it was in 150 major world news outlets. It was on the Today Show three times, on Good Morning America, in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the New Yorker. It was on TMZ and they all mentioned the exhibit. The museum has never had this kind of public awareness. We are a civil rights museum but this is clearly an audience-developing exhibit.”

Since his arrival from Alaska two years ago Kimura has focused on “bold, controversial, provocative, audience-developing and public programs” to raise the museum’s profile locally and internationally, as well as exposing “as many people as possible to the Japanese American story … and telling the Japanese story as an American story.”

The museum, which incorporated in 1985 and houses more than 60,000 artifacts, photographs, artworks, documents, and other collections, says Kimura, “has the steak, but we need the sizzle to bring new people and young people and younger generations to the museum.”

‘Bold and provocative’

Kimura, 46, is no stranger to “bold and provocative.” He is Yonsei, fourth-generation Japanese American, and fourth-generation Alaskan.

His great-grandfather immigrated to Anchorage in 1916 “when it wasn’t really a city yet. It was a stopping off point for building a railroad and the family legend is that he was the first Japanese to open a Chinese laundry and an Asian restaurant as well. “My family has been there ever since, outside the four-and-a-half years they were incarcerated during World War II. My father was born in the Minidoka concentration camp in Idaho.”

The camp was also where his grandparents converted to Christianity from Buddhism and later became very involved in All Saints Episcopal Church in Anchorage. His grandfather, an artist, designed the stained glass windows for the church, Kimura said. “He was also the first Asian art professor at Alaska Pacific University,” and a great-uncle was the first photography professor there.

The eldest of four sons, Kimura recalled growing up in a “semi-subsistence” family where hunting moose and caribou and salmon and halibut fishing provided the household’s main source of protein.

An undergraduate scholarship to Marquette University in Wisconsin sent him in an unexpected direction: he became involved in the university Episcopal Church and switched from pre-med to a double major of philosophy and theology. Eventually, he earned a master of divinity from Harvard Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a doctorate in the philosophy of religion from Cambridge University in England.

He served as a parish priest, university chaplain, professor, and the chair of the Department of Liberal Studies at Alaska Pacific University before joining in 2006 the Alaska Humanities Forum, a nonprofit agency using humanities to tell stories and impact the lives of Alaskans.

In that role, he helped bridge rural and urban experiences, including a teacher and student exchange program. He resonated with the Jesuit model of scholar-priest and considers himself a “tentmaker” like St. Paul, as he wrote in a 2011 article about his his bi-vocational ministry published in the Anglican Theological Review. (The article is available here.)

Yet, “at same time, five out of six Sundays I was serving at churches,” he said. “I’ve always been committed to bringing the sacraments to underserved communities and that’s what I was able to continue doing with this paid job. I was actually the priest at the last church to move from mission to parish status in the Diocese of Alaska, Holy Spirit in Eagle River.”

He came in second of five candidates in the 2010 Bishop of Alaska election, prompting a lot of soul-searching and the conviction that “one door closed, another opened up.”

When JANM offered him the president’s position in 2012, he and spouse Joy and children Lily, 5, and Julian, 12, moved to Los Angeles, for “a job that keeps me busy a lot of the time, traveling a lot of the time. When I’m not traveling, I’m helping out at St. Cross,” Kimura said.

The Rev. Rachel Nyback, St. Cross rector, said Kimura’s varied experiences bring a much-appreciated freshness to the Hermosa Beach congregation. “St. Cross is thankful to have Greg and his talented family with us. He has an Oxford mind with an L.A. mindset. Although his hometown in Alaska is a long way from Hermosa Beach, he is a perfect fit for St. Cross.”

Sparking some ‘sizzle’ and sadness

The life-sized images of people with full-body red, green, blue, black and gold intricately etched tattoos got Canon Bea Floyd’s attention — and fast.

“At first it was kind of like whoa, I’ve seen naked bodies before and tattoos before but not this many combined,” said Floyd, laughing, about a recent visit to the museum with the “Sociable Seniors” of St. Cross Church.

There they met with Kimura, who greeted the seniors and personally led their tour of the exhibit, “Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in the Modern World” a photographic collection of seven internationally acclaimed tattoo artists.

“One in every four Americans under the age of 40 has a tattoo and it’s probably even higher in Southern California,” Kimura told The Episcopal News. He hoped to show the artistry, symbolism, skill and rich history of the practice to a wider audience, he said.

“Japanese tattoo is a treasured art form and we wanted to do a story that would reclaim this aesthetic heritage,” he said. “We traced the connections to wood block prints, calligraphy, mythology, religious imagery to the contemporary Japanese tattoo scene.”

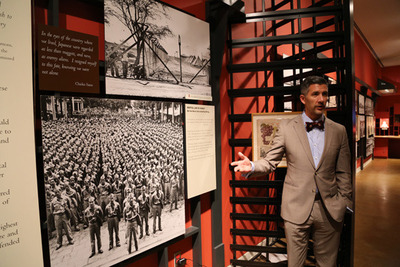

Greg Kimura shows a display concerning the World War II internment of Japanese Americans, part of the permanent exhibit at the Japanese American National Museum.

JANM’s core exhibit, “Common Ground: The Heart of Community” chronicles 130 years of Japanese American history, from immigration, Anti-Asian exclusionary laws to the World War II forced incarceration of Issei and Nissei, first-generation Japanese Americans and their children. A barrack from one of the concentration camps is a fixture of that exhibit.

Included in the collection are photos of the original building at Central and First avenues, one of the gathering places for Issei before they were taken to the Santa Anita racetrack and initially housed in horse stalls. (Another such gathering site was St. Mary’s Episcopal Church on Mariposa Avenue in Los Angeles.)

“There are people here at the museum who still remember the smell and indignity of having to live in places with horse dung … until they built more permanent internment camps closer to the interior, east of the Rockies,” Kimura said.

For St. Cross ‘Sociable Senior’ Audrie Wing, her first visit to the museum brought back bitter memories of the war-time camp experience endured by some of her friends.

Wing said seeing the exhibit felt very powerful. “My good friends were Nissei and I do remember my friend who was in Manzanar sending me an outline of her foot to buy her shoes … it was a terrible time. Greg did such a good job of explaining it in such a good way.”

While at the Alaska Humanities Forum Kimura edited Alaska at 50: the Past, Present and Next Fifty Years of Alaska Statehood (University of Alaska Press, 2009) and I Am Alaskan (University of Alaska Press, 2013), a collection of Brian Adams photographs reflecting the state’s cultural diversity.

Now JANM is full of stories to be told, he said. As the institution of record for Japanese Americans and the community’s historical memory, it houses extensive art and photographic collections as well as the archives of the Buddhist Churches of America, and the Japanese American Citizens League, a civil rights organization.

“Everything in Japanese America either starts or ends here at our museum,” he said.

It is also a civil rights museum, and one didn’t even have to like baseball to enjoy a recent Dodgers Baseball exhibit, which closed in September, he said.

“We told the story in a way that people instinctively knew there is something special about the Dodgers when it comes to civil rights,” he said. “They were the first to integrate in the modern history of baseball with Jackie Robinson, an African American.”

But, he added, the Dodgers also had “the first mega Mexican pitching start with Fernando Valenzuela. They had the first mega Japanese pitching star with Hideo Nomo and the first Korean pitching star in Chan Ho Park. I wanted to show this connection and commitment … of their outreach to minorities and how sports is a way of bridging differences.”

‘A reason to come through our door’

Greg Kimura points out items assembled for the Japanese American National Museum’s current special exhibit on Sanrio’s “Hello Kitty.” Kimura’s comment in a pre-exhibit interview that the much-loved character might not be a cat at all went viral on the Internet, bringing the museum unprecedented publicity.

One of Kimura’s goals is “to give folks who might go to MOCA [Museum of Contemporary Art] and walk right past us, a reason to come through our front door.”

With some 20,000 yearly visitors, 60 employees, 200 volunteers and an annual $6.3 million budget, he believes in hiring creative people, giving them structure and getting out of their way so they can work.

He also believes the board — which includes such notables as chairman emeritus George Takei of Star Trek fame — hired him to help bridge community identity amid changing circumstances.

“I’ve been here two and a half years and there’s still a lot of struggles. Our community will be the first Asian American community by the next census to be majority mixed-race,” said Kimura, who is happa, or ethnically half-Japanese.

“It’s either us or the Indonesians. We’re a bellwether for the rest of the Asian American community and the dynamics are changing. We’re transitioning from the people who lived through the war-time experience of internment to having very few folks with a living memory of it.”

Which only heightens his desire to expose as many people as possible to the Japanese American story to make sure it doesn’t ever happen again, to safeguard civil liberties and “to make sure that America remembers it’s not the color of skin or shape of eyelid but content of character that matters.”

A recent 30-year retrospective on the movie “The Karate Kid” brought actor Ralph Macchio, Academy Award-winning director John Avildsen and the Cobra Kai gang, as well as the family of the late actor Pat Morita, to the museum, he said.

“His widow and daughter presented the museum with the 442nd uniform that was featured in that movie,” Kimura said. “That’s an important artifact for us because that was the first time in a popular movie where the interment experience and 442nd segregated units were featured.”

Upcoming exhibits will include photos from the camp experience; the World War II veterans, connections with Polynesia and food, “whether it’s sushi or ramen,” said Kimura.

For now, he is enjoying telling the story through exhibits but believes ultimately he will return to more extensive parish life. Recalling times of celebrating Christmas masses in underserved communities at 40 degrees below zero, he said of his dual vocations, “Being a cleric is the toughest job and by far the most meaningful.”