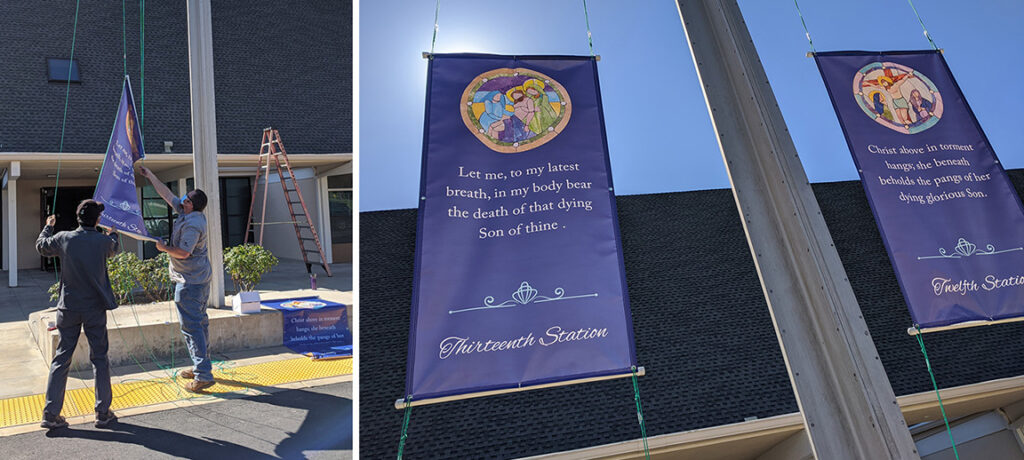

Yong Muhn and Chris Walker hang Stations of the Cross 12 and 13 at St. Mark’s Church, Upland. Photo: Serena Beeks

Station 11 in the ecumenical Stations of the Cross is located at Granite Creek Community Church, Claremont. It was created by Los Angeles artist and designer Bobby Doran. Photo: Keith Yamamoto

Andrew Kilkenny, 34, knelt on ground softened by pine needles outside St. Ambrose Episcopal Church in Claremont, the third stop of a drive-through, pandemic-inspired interactive Stations of the Cross commemorating the last hours of Jesus’ life.

At Station 3, visitors tap on a pre-recorded audio reflection and are invited to leave their cars and take a knee, recalling the first of several times Jesus stumbled along the road to the crucifixion. The reflection invites consideration of the crushing burdens “of racism, sexism, homophobia and all kinds of biases that bring us to our knees.”

For Kilkenny, the experience became a moment to ponder “what we are kneeling for, in terms of racial or social justice. I was never given space to reflect about Colin Kaepernick, kneeling,” he said. “There is something powerful and profound, to take that space and do it yourself and think about how it all relates to Jesus, falling for the first time.”

Kaepernick, the Black former San Francisco 49ers quarterback, drew both rebuke and acclaim for kneeling during the playing of the national anthem before games, in protest of police brutality and racial inequality in the United States. Now a free agent, he was released in 2017 in a move widely regarded as retribution for his activism.

Station 3, “Jesus falls for the first time,” is at St. Ambrose Episcopal Church, Claremont. Photo: Keith Yamamoto

Kilkenny, an entertainment technology engineer, designed the smartphone-accessible “L.A. Stations” as a safe Stations of the Cross alternative during the pandemic. Racial reckoning, homophobia, sexism and other social inequities figure prominently in reflections along the 7.4-mile drive to nine Claremont and Upland churches, each hosting one or more of the stations.

Google and Apple maps supply route directions, as pilgrims can listen and follow along Jesus’ path to the cross, similar to a museum self-guided audio tour. The stations were opened March 3 and will continue through Holy Saturday, April 3.

As at St. Ambrose, visitors may leave their cars at various stops to explore deeper connection. The Rev. Jessie Smith, St. Ambrose’s rector, compared praying the stations to superimposing the ancient story onto her current realities.

“It felt like weaving the narrative of Jesus’ life into the neighborhood where I’m living,” said Smith, whose church also hosts Station 2, where Jesus takes up his cross. There, Smith’s recorded message invites pilgrims to “consider the starving of this world and the vast gap between the hungry and those who have plenty.”

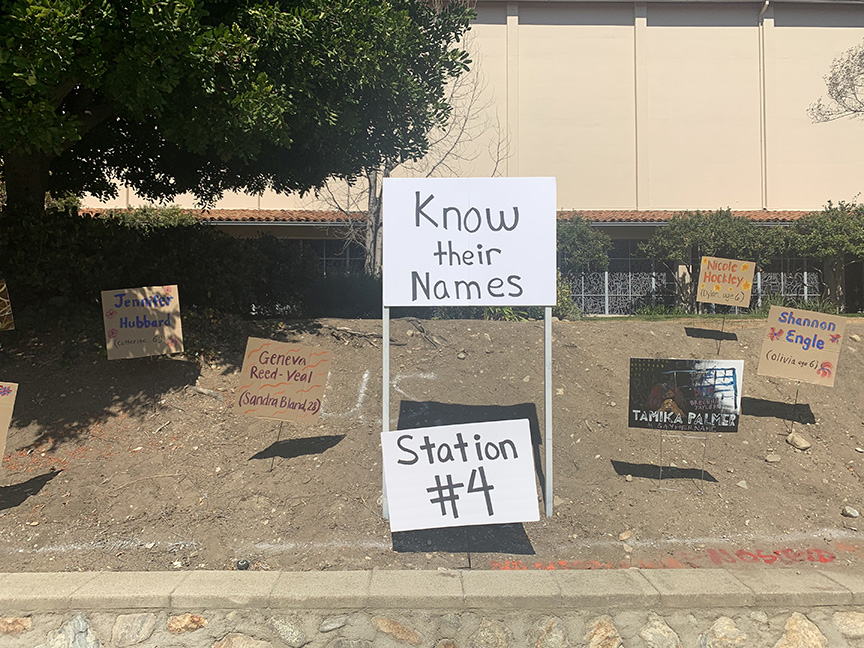

Station 4 at Claremont United Church of Christ, “Jesus meets his mother,” recalls the names of mothers who have lost children to violence. It focuses on the mothers of first and second graders murdered in 2012 at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut, and those of black men and women who have died in police violence. Photo: Keith Yamamoto

Stations of the Cross, also known as the Way of the Cross or the Via Dolorosa, refers to a series of 14 images, typically mounted inside churches, representing Jesus’s death. The stations begin with Jesus being sentenced to death; by Station 14, he is laid in the tomb. The ancient spiritual practice originated in Jerusalem; during Lent and especially on Good Friday, the faithful travel from station to station, pausing to pray and reflect about the meaning of Jesus’ life and death.

For Rick and Mary Beth, who declined to give their last name, a stop at Station 4, “Jesus meets his mother,” at the Claremont United Church of Christ where they attend worship, brought heartache and a sense of the grief and pain of mothers who have lost children to violence.

“I can’t begin to know what it feels like to put a name on one of those signs,” said Mary Beth, indicating a black and white sign bearing the message, “Know their names.”

Surrounding it, other hand-written signs bear the names of Shannon Engle and Michele Gay, whose daughters, Olivia Engle, 6, and Josephine Gay, 7, died during the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shootings in Newtown, Connecticut.

Others display the names of Black mothers whose children were killed by police: Sheneen McClain, mother of Elijah, 23; Samaria Rice (Tamir, 12); Gwen Carr (Eric Garner, 43); Tamika Palmer (Breonna Taylor, 26) and more.

Station 5, commemorating Simon of Cyrene carrying Jesus’ cross, offers visitors a chance to inscribe a prayer or thought. Photo: Keith Yamamoto

A message pre-recorded by the Rev. Jennifer Strickland, Claremont UCC’s co-pastor, invites pilgrims “to speak each of these names aloud” and to offer the mothers a moment of silence to honor their loss. Visitors are also invited to include the names of additional grieving mothers on blank signs provided, and to plant them in the dirt alongside the others.

Strickland said reflecting about Mary’s anguish prompted recognition of “how helpless, devastated and angry a mother must feel when facing the loss of her child” in current contexts, including Sandy Hook and elsewhere.

She wanted to acknowledge “how mothers of Black children must feel so terrified constantly, because there is such threat to their children’s lives for no reasons outside the color of their skin,” she said.

Several yards away in front of the church doors, Station 5 commemorates Simon of Cyrene, carrying Jesus’s cross. Visitors are invited to take a multi-colored mini-scroll of paper bearing suggestions of such random acts of kindness as: send a care package to a service member; learn CPR; leave a positive comment on a news article or blog post; give an extra tip and write an encouraging note along with it.

A few miles away, at the Granite Creek Community Church in Claremont, larger-than- life-sized parking lot artistic depictions of Station 10 (Jesus is stripped of his garments) and Station 11 (Jesus is nailed to the cross) are lit at night. The two are poised in sharp contrast to one another; purposefully so, according to the Rev. Meko Kapchinsky.

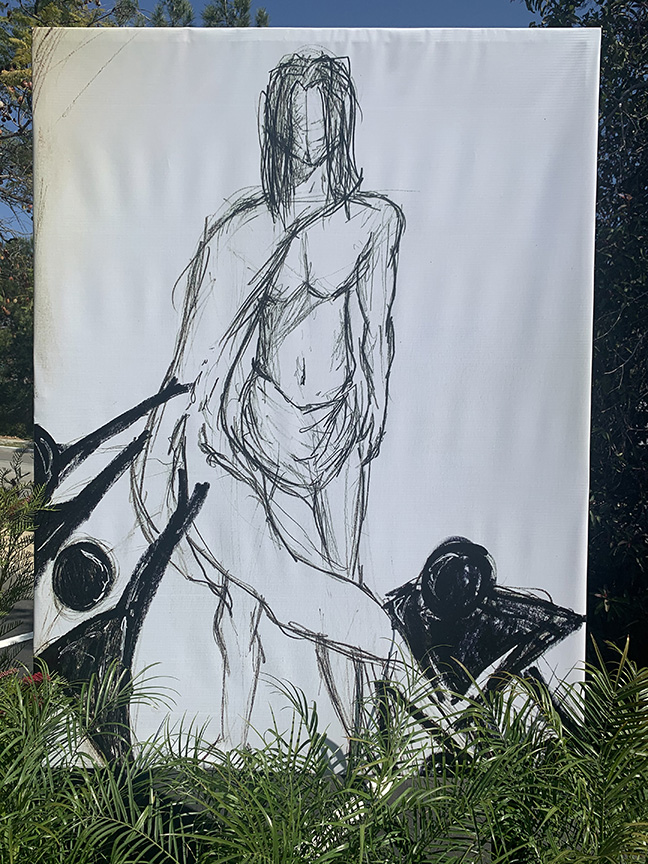

Station 10, “Jesus is stripped of his garments,” at Granite Creek Community Church in Claremont, was created by Sophia Kapcinsky, 14. Photo: Keith Yamamoto

Her daughter, Sophia, 14, created the 4.5-by-6-foot black-and-white image of Jesus, “getting his clothes ripped off. It is very stark and harsh. It frames out theologically … (that) there is nothing pretty about it. There is nothing to get lost in.” An accompanying pre-recorded message reads a graphic Scriptural account of Jesus’ agony.

The image contrasts with Station 11, a vibrant kaleidoscope of blues, yellows, browns, reds, painted by Los Angeles artist and designer Bobby Doran, depicting Jesus nailed to the cross.

Commemorating the Stations is not part of her church’s evangelical tradition, but Kapchinsky “felt like the ceremony and ritual can help us process our faith at a different level, especially now in this culture, where everything is so warp-speed fast.”

The collaborative journey is “a God-send because it allows people to hit the pause button and sit and meditate and process and listen; like, what is God trying to say to them? Given our society right now and how everybody’s so absorbed with online stuff, it asks you to sit and just be before God. That’s a super valuable lesson especially in our present day and age.”

Focusing on the program and garnering collaborative energy, additionally, has been “a great rallying point for churches and people,” she added.

“There’s no debating this. There’s no conspiracy theory behind it. It’s just shut up and go and sit before these things and process them and have ears to listen. That’s a lost skill in this day and age.”

Julia Warren, 27, a parishioner at St. Mark’s Church in Upland, which hosts Stations 12 (Jesus Dies on the Cross) and 13 (Jesus is Taken Down from the Cross), drove from Pasadena to take the two-hour “really cool” pilgrimage.

“Each station was unique to each community and there was a lot of variety,” she said. “It was like a potluck meal. Some people brought paper plates. Some made their family’s secret pie recipe, but you want all of it at the potluck.”