Bishop John Harvey Taylor preaches to a packed church at St. Barnabas’, Pasadena’, centennial service on June 11. Photos: Janet Kawamoto

Prior to the centennial service, Bishop John Harvey Taylor blessed a new chancel cross crafted by parishioner Robert Edwards in memory of his mother-in-law, Edna Pierre Hodgson. Edwards served as the bishop’s chaplain during the service. Photo: John Taylor

[The Episcopal News] “They Thought They Buried Us, But God Actually Planted Us,” reads a banner outside St. Barnabas’ Church, Pasadena, which on June 11 celebrated its centennial year as a historically Black congregation of the Diocese of Los Angeles.

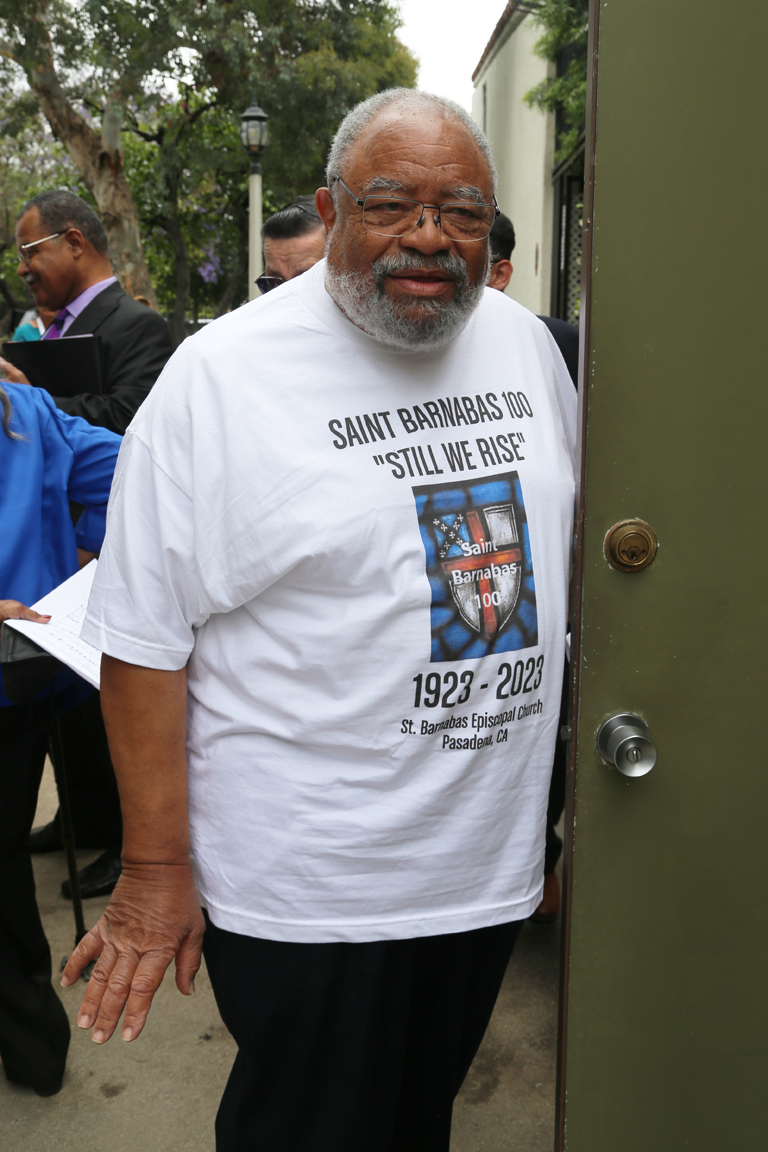

The celebration committee, chaired by parishioner Marco White, chose the theme “St. Barnabas 100 – Still We Rise” – alluding to a poem by Maya Angelou – to represent the congregation’s long, faithful journey to their centennial year.

Lively, determined and now sustained by a diverse congregation, St. Barnabas’ began in 1909 when eight Black women – “the matriarchs” – met in the home of Georgia Weatherton and began an Episcopal mission society that they named “St. Barnabas’ Guild.”

The matriarchs launched their worship community because they and their families – many of whom came to California to escape Jim Crow laws in what is now called “The Great Migration’ – were not welcome at nearby Episcopal churches, including All Saints, Pasadena – now a stronghold of diversity and inclusion, but in the early 1900s a place of white worship and privilege.

In his sermon for the centennial service, Bishop John Harvey Taylor drew from the Book of Acts, in which Stephen, one of the church’s first deacons, became its first martyr when he was stoned to death in Jerusalem for blasphemy when he preached the gospel. After his death, believers in Jesus were scattered – “I’m stressing the scattering,” Taylor said – and some ended up in Antioch, where they shared their new faith to both Jews and Gentiles.

Members of the choir and congregation join in the closing hymn.

“They heard about this back in Jerusalem, and they sent Barnabas to investigate,” said Taylor. “Barnabas was so excited that he went to get Paul, and he brought him to Antioch, because Paul was all about ministry to the Gentiles. And they spent a year there spreading the Good News and earning at last the name Christians, and soon Antioch became headquarters for Christian mission, the base camp of a global faith of love and salvation and justice. Some of the believers were scattered; yet by their faith, they transformed the whole world. And that brings us right back to the St. Barnabas of Pasadena story.

“This was a dark time in American Christianity, early in the 20th century,” said Taylor. “God help us, it was true in most churches in American Christianity [that] such a misinformed gospel was preached. It was understood that people of African descent and white people should not worship together. That they should not gather under the same roof and talk about the Savior who says the meek would inherit the earth, and that his Father would lose none of those whom he had made; the Savior who said the last shall be first and the first shall be last; the Savior who said that I should always behave toward others exactly the way I want to be treated. So the believers were scattered.”

But, he said, “they found their way to Antioch; Georgia Weatherton’s house.

“Let’s consider this fundamental reality of our faith,” Taylor continued; “that our God in Christ always uses those who are scattered, as the Christians were out of Jerusalem, as your forebears were out of Pasadena; God always uses them to spread the good news.”

He concluded: “God’s love cannot be contained or resisted. God’s favor could not be hoarded or withheld from the marginalized by those who happen to have the privilege of institutional possession. In Christ, the scattered seeds will always take root as they took root here on Fair Oaks Blvd. This morning St. Barnabas is in full bloom. Congratulations. And still you rise!”

Marco White, centennial chair, gets the festivities started as master of ceremonies.

Stories, presentations and soul food

After the service, the Rev. Marianne Zahn, priest-in-charge of St. Barnabas’, opened the pre-luncheon celebration by introducing clergy from a Spanish-speaking Catholic congregation that uses St. Barnabas’ for worship, who offered prayers and thanksgivings for both congregations. Zahl then called Marco White as master of ceremonies, describing him as the person who had the idea of celebrating the anniversary and worked tirelessly with his committee to plan the event.

“When I came up with this idea, about six months ago, I was just joking,” quipped White, a lifelong member of the parish. “Let’s just keep going on our journey of love, St. Barnabas style.”

U.S. Representative Judy Chu of California’s 28th District presented the parish with a Congressional Record that outlines St. Barnabas’ history – “a symbol of resilience and hope for generations to come” in Pasadena – that has been incorporated in the official records of the U.S. Congress. Citations also were presented by Justin Jones of the Pasadena City Council; by a representative from the office of Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger of the Fifth District; Allen Edson, president of the Pasadena NAACP; and Chris Holden of the California State Legislature.

Parish historian and griot (a West African term for a village storyteller) Michael Mims, a retired professor of photography at Pasadena City College, shared stories of coming to St. Barnabas’ as a young child with his aunt, founding matriarch Rosebud Mims, becoming an acolyte and gradually convincing almost his entire family to join the parish.

Parish elders Sylvia Wiggins and Michael Mims share stories of St. Barnabas’ past.

Also sharing stories was Sylvia Wiggins, who came to St. Barnabas in 1939 at the age of one. She reminisced about the several parish guilds, including St. Mary’s Guild, of which she was a member and president. “St. Mary’s Guild was known for the best fried chicken dinners in all of Pasadena” and even Los Angeles County, she said, “because people came from far and near to have one of those chicken dinners.”

She recalled annual beach parties, Sunday school Christmas programs, barbecues, and especially the “Refreshment Day” tea traditionally held in Lent. “We used the finest silverware and lace tablecloths on the tables, and we served tea sandwiches, tea and coffee. And everybody would come and just enjoy the tea that we had.”

A history of community, perseverance and service

The St. Barnabas congregation was established in 1923, served by a lay reader from All Saints and the organist from St. Philip’s, another historically Black congregation in Los Angeles. In 1932, with support from then-Bishop Bertrand Stevens, St. Barnabas’ Church was admitted into union with Diocesan Convention as a mission congregation.

The Dobbins family of All Saints donated the property at 1062 N. Fair Oaks Avenue, and the Fleming family gifted the church building, built in 1933. An existing building on the property served as the parish hall.

Bishop Stevens called the Rev. W. Alfred Wilkins, a young African-American priest from New Jersey, as the first vicar of the new mission. Wilkins, with his wife, Lydia – who died in 2010, age 106, as a member of All Saints – served at St. Barnabas’ until 1943, when he became an army chaplain.

The Rev. Alfred E. Norman became the next vicar, but after two years left to serve a congregation in Watts. The Rev. Jesse D. Moses II became vicar, concurrently serving as the first black principal in the Pasadena Unified School District.

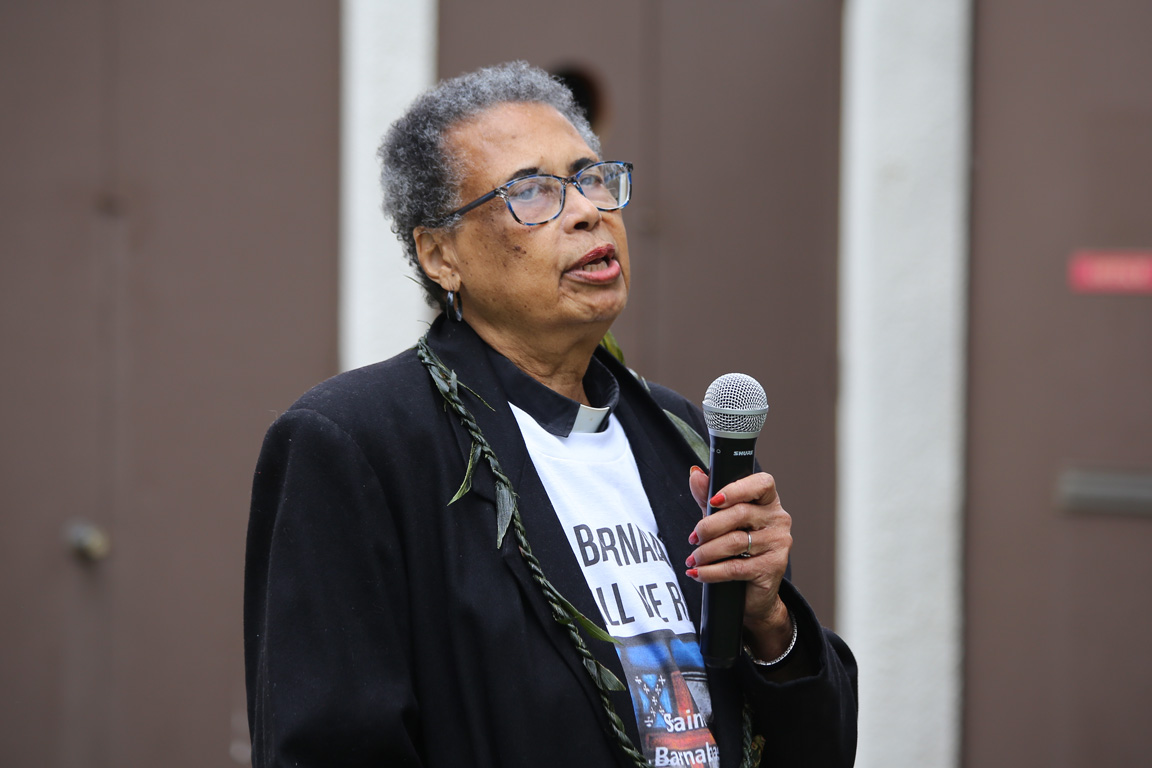

Bishop Taylor addresses the assembled members and friends of St. Barnabas’ Church after the centennial service.

Upon Moses’ resignation in 1951, Norman returned to St. Barnabas, where he led the congregation as it grew and became a neighborhood fixture and gathering place. A new parish hall, designed to double as a community center, was built and dedicated in 1972. At that time, according to a souvenir booklet produced for the occasion, St. Barnabas’ had a lively and varied ministry that included several women’s guilds in addition to an ECW chapter and a men’s guild. The congregation also sponsored Boy Scout Troop 11.

During Norman’s long tenure, members of St. Barnabas’ survived difficult times, including destruction of neighborhoods for the construction of the 210 freeway. Lifelong member Phlunte Riddle, former Pasadena police lieutenant and juvenile justice officer and current candidate for state assembly, told the centennial gathering that her extended family lost not one, but two homes to eminent domain, but emphasized that the community persevered and “planted seeds” that allowed St. Barnabas’ to thrive.

Norman retired in 1977 and was followed by the Rev. Ivor Ottley. Under his tenure, the congregation renovated the church building, installed a new organ, and were enthusiastic users of The Episcopal Church’s new worship resources, including the 1979 Book of Common Prayer and “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” a hymnal of music from the African American-inspired gospel tradition.

Three longtime members of St. Barnabas’, all of whom were acolytes there in their younger days, enjoy the centennial festivities.

In about 1983, St. Barnabas’ Church applied for parish status, which was granted by Diocesan Convention in 1988. Ottley became the first rector. He resigned in 1990 due to ill health, and was succeeded by the Rev. Patricia Bennett, who served for about three years before resigning, also for health reasons. The Rev. John M. Larson was named priest-in-charge; he oversaw much-needed repairs and stewardship of the church’s building and grounds and encouraged greater community outreach.

The Rev. Anthony Glenn Miller became the next rector in 2002. During his tenure the congregation continued to increase its involvement in the community, including hosting monthly dinners at the Union Station Homeless Services Center in Pasadena.

Beginning in 2011 the Rev. John Goldingay, an eminent biblical scholar at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, served as volunteer priest-in-charge. When he retired, the Rev. Mark Bradshaw, a son of the parish who served as lay associate, deacon and curate between 2014 and 2018, became rector, serving until 2020 when he joined the U.S. Air Force as a chaplain.

Four lifelong members of St. Barnabas, all of whom were baptized at the parish, pose during the June 11 centennial party.

The Rev. Marianne Zahn was called as priest-in-charge in 2022, beginning her ministry as St. Barnabas’ emerged from virtual worship forced by the Covid pandemic and began the celebration of its 100th year. Zahn is assisted by retired priest the Rev. Argola Haynes.

St. Barnabas’ hosts three Alcoholics Anonymous groups; a Spanish-speaking Catholic congregation that worships on Sunday afternoons; and a Spanish-speaking Pentecostal congregation on Friday and Sunday evenings. The Episcopal congregation participates in programs to feed the homeless, supports local families through the Jackie Robinson Community Center (located next door to the parish), provides college scholarships for Pasadena Unified School District graduates, supports Episcopal Relief & Development, stocks a sidewalk free food pantry; and sponsors a Little League team.

— Information about St. Barnabas’ past is drawn from the history compiled by Matthew Mims, available on the parish website. On permanent display in the parish hall is a collection of photos, artifacts and articles that Mims has collected telling the stories of St. Barnabas’ Church and the city of Pasadena.