Participants in the online town hall meeting held July 19 by the Bishop’s Commission on Gospel Justice and Community Care discuss the need for better responses to mental illness and other crises. Clockwise from top left: Moderator Sam Pillsbury, Taun Hall, Gigi Crowder and Pete Cohen. Photo: screenshot

[The Episcopal News] Lives will be saved by the new 9-8-8 national crisis line and related mental health-care alternatives to unnecessary incarceration or tragic deaths, U.S. Congresswoman Katie Porter and other speakers said during a July 19 online Town Hall hosted by the diocesan Commission on Gospel Justice and Community Care. (Video of the full 90-minute town hall program is here.)

California state funding of the Miles Hall Lifeline Act (AB988) is now key to optimal implementation of new call centers, said town hall speakers, notably Taun Hall, mother of the late Miles Hall, a 23-year-old man who was fatally shot during a local police response to a mental-health crisis that he was experiencing on June 2, 2019 in Walnut Creek, Calif.

In advance of an Aug. 1 state senate appropriations committee meeting, letter-writing to lawmakers has been recommended by the diocesan commission, notes its chairperson, Sister Patricia Sarah Terry of St. Cross Church, Hermosa Beach. [Please see related story for further information.)

Urging support also for the pending bipartisan Mental Health Justice Act that she authored at the federal level, Porter said this bill will replicate an Orange County model to “allow police to focus on public safety while building deeper trust between officers and the people they serve, and it will provide mental-health first-responder units with the resources they will need to be successful.”

U.S. Representative Katie Porter Official photo

Porter – an Episcopalian and the first Democrat to represent California’s 45th congressional district comprising Irvine, Tustin, Lake Forest, Laguna Niguel, and parts of Anaheim – offered her presentation by pre-recorded video introduced to the Town Hall by Bishop John Harvey Taylor.

Welcoming town hall attendees, Taylor pointed to the origin of the commission and its consensus that “one of the issues that we wanted to take up was to make sure we did all we could to advocate for the resources which are so desperately needed to make sure that local law enforcement is able to send trained personnel to situations where armed response would be dangerous for the people of God in our streets.”

The commission was formed after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, Taylor said, encouraging his listeners to learn more about the group’s work and to consider joining its membership.

“The Executive Council of our Episcopal Church called on dioceses to find a way to be in urgent conversation with local law enforcement about issues of equity, fairness, safety, and racism,” Taylor said. “And so we understood that challenge and formed this commission in the fall of 2020.”

“I’m proud to be a partner in that work,” Porter said, citing earlier conversations with Taylor and Terry and praising the diocese for “actively advocating for strong mental health-care policies.”

“Our communities are facing a mental health epidemic,” she added. “One in four adults have reported symptoms of anxiety and depression since the pandemic started, and right here in Orange County our Children’s Hospital saw a 40% increase in admissions last year.”

“This is not just an abstract policy debate,” Porter said. “Far too many people experiencing crises can face matters of life and death in getting care.”

“A recent study found that one in four fatal police encounters ends the life of a person with severe mental illness,” she said. “Many people cycle in and out of our broken prison and justice systems when what they need is treatment and care.

“We should be connecting people in crisis to care, not putting them in jail,” Porter said. “Police officers will be the first to tell you that their job is to keep communities safe, not to provide healthcare.”

‘From pain to purpose’

Panelists joining Hall – founder of the Miles Hall Foundation – were Gigi Crowder, executive director of the National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI) in Contra Costa County, Calif., and Pete Cohen, a retired sergeant in San Diego Police Dept., who specialized in peace-keeping services and training that pairs patrol officers with mental healthcare professionals.

Moderating the panel discussion, the Rev. Sam Pillsbury – a diocesan deacon who is a chaplain at L.A.’s Twin Towers jail and a retired professor at Loyola Law School – pointed to Christ’s own example in caring for people in crisis.

“One of the things that we see in the gospels as Christians is how often Jesus is encountering hurt people and healing them,” Pillsbury said, “and how often those hurt people are folks that we would today say have mental illness, people who are really tormented to whom he brings peace, which I think is a terrific message to us in what we are called to do in all varieties and ways of doing healing.”

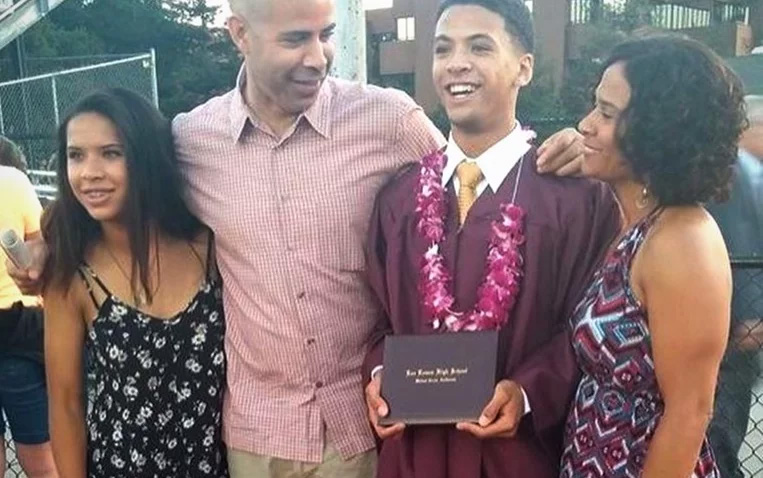

Miles Hall, pictured with family at his high school graduation, was killed by police while he was suffering a mental health incident. Courtesy photo

Hall pointed to her late son’s own deeply held faith, explaining that he was always eager to share his Christian beliefs with others. His practice of knocking on neighbors’ doors to discuss spirituality put him at added risk once it became clear that he was experiencing mental health crises. Hall was vigilant in alerting neighbors and local police to their son’s condition, fearing for his safety, she said.

Hall laments the system that requires those suffering from mental illness to reach the point of a “5150” 72-hour hold before authorities provide critically needed care. It’s a “fail-first system,” she said.

Hall’s worst fears were realized the day that her son, experiencing serious symptoms and holding a garden tool, was confronted in the cul-de-sac outside the family’s suburban home by police officers who escalated his distress by “bean-bagging” him, shouting his name, and firing a fatal shot.

“Our loved ones should not be criminalized,” said Hall, who contacted NAMI in relation to her son’s condition and death. “Say his name, Miles Hall,” she said in concluding her remarks.

NAMI executive director Crowder, her voice breaking with emotion, spoke of the vitality of Miles Hall and her resolve to support his parents in seeking justice and implementing added measures for public safety.

“Sadly, in Contra Costa County he was not the last individual killed by law enforcement – four young men, all living with mental illnesss, have since been killed by law enforcement in this county, and it has to stop,” Crowder told the town hall attendees. “There’s no way you can justify that four young men of color were killed by law enforcement.

“I work daily with law enforcement to try and improve outcomes,” Crowder said. “I’m not talking about not having law enforcement, I’m saying when they’re not doing the job in the American system with producing the best outcomes, then they should not be on the force.

“And if we’re funding law enforcement with our tax dollars to go to get trained – we should be funding licensed clinical social workers, and giving them free education, as well,” she added.

“From pain to purpose, from tragedy to triumph, Miles Hall has saved lives, and will continue to save lives,” Crowder said, “and the governor must sign the bill and so do quickly, and counties must set aside the funds needed to have a non-police response.”

“All counties should have a place to take their loved one before it gets to such extreme measures,” a place “reflective of all the communities,” she said, “and we need to stop caging black and brown individuals that live with mental health challenges.”

As a retired San Diego police officer, Cohen – whose late father, Albert, was well known in Southern California as a UCC minister and ecumenical justice leader – shared perspectives on his 27-year career as a peacekeeper “formed in the mold of social justice,” emphasizing that “it’s critical that law enforcement personnel are included in this dialogue.”

Commending the diocese “for continuing to have this dialogue as a priority,” Cohen said that when situations ranging from the Rodney King beating to those less publicized, “it seemed like the topic would be a priority… and then we’d be back to basically status quo when we wouldn’t be talking about matters of consequence when it comes to law enforcement and its role, and its effect on certain members of the community, and in particular people of color, and more particularly than that, black and African American citizens.”

Noting his upbringing in a progressive and multiracial family experienced in Pasadena school integration, Cohen said he was drawn to a career in peacekeeping as an athlete who “was looking for something physical to do, and something service-oriented to do. I’d heard a lot of bad things about law enforcement… and I thought maybe I need to see if I can change some of that.”

Cohen said he appreciated being part of the San Diego Police Department which was “really making an effort to promote community-oriented policing, and problem-oriented policing. One of my primary roles was as a Psychological Emergency Response Team (PERT) supervisor as well. San Diego was one of the first agencies that created this concept where they would have county mental health professionals riding along in police cars with peacekeepers.”

Calling the new 9-8-8 mental health crisis hotline “outstanding,” Cohen added, “at the same time… I want to make sure we understand that there are times – regardless of the condition of the individual, they might be putting themselves or others at risk – it may be best to have some of the tools that law enforcement has to offer. I want to get that on the table as a topic of conversation.”

Pillsbury asked, “What do you see as the challenges within a police department, and particularly what are the cultural mindsets that get us to a place were the wrong things happen at the scene… that a person gets treated as a threat that they are not?”

Cohen replied by pointing first to history: “I fully understand that what is going on in law enforcement is the result of hundreds if not thousands of years of history, and particularly 400 years on this soil. Because I understand that, and I’m willing to talk about that. …

“It’s far more difficult more difficult for active peacekeepers to be engaged in this dialogue,” Cohen added. “The main challenge for people who are in law enforcement organizations is to be open to dialogue, to be open to being disagreed with, to be open to discussing historical context and how we got here… to be open to systemic issues of racism, mental health, addiction.

“Creating dialogue is going to be one of the greatest challenges,” Cohen said. “There are chiefs of police who are more than willing to be part of this dialogue… and there are people at various levels of organizations throughout the country who are capable of participating in this dialogue, but it’s too few and too far between.”

In a closing prayer, the bishop underscored the need for care of those at risk, and also gave thanks for all who participated in the town hall. At the outset of the program, he thanked Terry “for her visionary leadership at the helm of this commission. She’s an attorney, a contemplative, an activist and advocate, and a pastor. The gifts she’s brought to the work of this commission – which will mark its second year of activity this September — have been incalculably great.”

Terry noted that the town hall “was sponsored to help all of us better understand why mental health justice should be of concern to all communities of faith… and how important it is for mental health professionals to respond to mental health crises.

“When police respond and rely primarily on standard police training and tactics they learn for standard police work, the results are often sadly tragic,” Terry said. “For more just and compassionate response, additional resources are needed. Our hope is that we can make our communities more just as well as more safe.”