Lydia Lopez. Photo: Ben Rodriguez, Sr.

[The Episcopal News] Canon Lydia Lopez – who for more than 50 years served the Diocese of Los Angeles and wider Episcopal Church as a lay leader, civil rights advocate, and self-described “interpreter” across cultures – died Jan. 16 at Huntington Memorial Hospital in Pasadena. She was 80 and until recent months was engaged in ministry and research projects at her Alhambra home.

Survivors include her son, Alejandro, and daughter-in-law, April; grandchildren Aaden and Ava; nephews Ben and Michael Rodriguez, nieces Eva Marie Rodriguez Morris and Marcia Dyer, and their families; and many friends.

Bishop John Harvey Taylor will preside at memorial Eucharist set for 2 p.m. on Saturday, Feb. 18 (livestream here) at Pasadena’s All Saints Episcopal Church, where Lopez – named an honorary diocesan canon in 2000 by then Bishop Frederick H. Borsch – was an active parishioner. Remembrances will reflect the scope of Lopez’s achievements as a Chicano movement activist and community organizer, and in diocesan ministries including General Convention deputy, member of the Commission on Ministry among other appointed bodies, and her service as diocesan associate for communications and public affairs from 2000 until her retirement in 2010.

In a message notifying the diocesan community of Lopez’s death, Taylor underscored outcomes of her faith in action.

“If working people in Los Angeles have a convenient Metro stop in their neighborhood, it’s because of Lydia. If farmworkers are treated with a measure of dignity and respect, it’s because of Lydia. If a secularizing culture is still inspired when people of faith act in our world according to the values they proclaim with their words, it’s because of people such as Lydia,” Taylor said.

“My newspapering mother, Jean, first introduced me to Lydia a third of a century ago at All Saints in Pasadena. She was so proud to know her, and I was, too,” Taylor added. “I’ll cherish our long conversations in recent years, and her wise counsel. She leaves a space in our diocesan family that only our continued ministry according to her example can fill.”

Lopez was elected in 1981 as president of the United Neighborhoods Organization. Photo: Ruth Nicastro

The Rev. Mike Kinman, All Saints’ rector, described Lopez as “a world changer and a powerful force. What I will always remember about her is her mischievous joy. That joy was the heart of her power to move mountains and to mount movements.”

“I knew Lydia for many years,” State Sen. Maria Elena Durazo – who represents central and east Los Angeles and is a vice chair of the Democratic National Committee – told The News. “She took me under her wing and taught me so much…. I was so new to clergy activism, I wasn’t quite sure how to handle myself. She was such a natural organizer. Part of her success was making me laugh. Rest in power, my dear sister Lydia.”

One of the first to post a tribute on Facebook, the Rev. Wilma Terry Jakobsen, a priest formerly on the All Saints’ staff, wrote from South Africa: “Dearest Lydia… I’m not surprised you passed away on MLK day,” highlighting Lopez’s commitment to the vision and witness of Dr. 20 Luther King Jr. “Your memory is treasured.”

Jakobsen, a former chaplain to Cape Town’s late Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, assisted Lopez in tending longstanding solidarity shared by L.A. Episcopalians and South African Anglicans, reflected in Lopez’s work to arrange a virtual 90th birthday gathering for Tutu via Zoom in 2020.

“Policy, politics, and parties: that’s what I do,” Lopez quipped while arranging a 2007 gala dinner for Tutu hosted in Los Angeles by then-Bishop J. Jon Bruno, for whom Lopez also staffed local initiatives on healthcare reform and civil rights. “It’s interesting how these three portfolios often intersect as a nexus for progress.”

Like Tutu and King, Lopez was no stranger to being arrested for civil disobedience. “I was pregnant the first time I was arrested,” she recounted in a 2018 talk, referring to a 1970 Christmas Eve mid-Wilshire church protest at which she and her husband joined other Chicanos decrying conditions of poverty among Latino Angelenos.

“I had to wait for a long time, so by the time I was put into my jail cell it is dark, and I am given a mat to sleep on the floor. The door clangs, and I cry quietly,” she told listeners at All Saints. “Years later I overheard my son saying to his playmates, ‘Oh, yeah, my mom and I went to jail to make things better.’”

Lopez’s perspectives on this protest are also included in historian Felipe Hinojosa’s 2021 book Apostles of Change: Latino Radical Politics, Church Occupations, and the Fight to Save the Barrio, published by the University of Texas Press.

Lopez speaks at a centennial celebration for Church of the Epiphany, Los Angeles, in 2013. She was an active member of that congregation – known for its central role in the Chicano movement and other social justice actions – for many years. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Church of the Epiphany: ‘I was home’

On a picket line two years earlier, Lopez first learned of East L.A.’s Episcopal Church of the Epiphany, Lincoln Heights, and its community-minded outreach that brought her back to Sunday services years after she had left her childhood Baptist church in Whittier due to sociopolitical stances different from her own.

“In the year 1968 the drop-out rate of the high schools in East Los Angeles was 50 to 60 percent,” Lopez said. “Students had walked out of the four high schools, and 13 Chicanos were arrested and indicted by the Los Angeles Grand Jury for organizing the walkouts. We as supporters in the community were demonstrating around the Hall of Justice where the Grand Jury met.

“Then who is on the picket line? Two Baptist ministers, one Presbyterian pastor and three Episcopal priests (Epiphany clergy John Luce, Roger Wood, and Oliver Garver, later elected the diocese’s bishop suffragan). God has a sense of humor and good timing.

“When you’re walking back and forth on a picket line you have a lot of time to talk and get acquainted. When I was learning about church, I was told that the biggest fiesta of the year was Epiphany. I asked my friend, ‘What is Epiphany?’

When Lopez arrived for the celebration at the Church of the Epiphany, she was deeply moved. “It was the first church to use Mariachis in the Mass. And a lot of other cultural symbols before it caught on elsewhere. What a colorful space, alive with papel picado [paper flags], and the bread and wine. I wept. I knew nothing about the Episcopal Church, but it did not matter. I was home, in a special and holy place. A place for me as a Christian and a Chicana. I couldn’t resist it.”

“Lydia had a relentless curiosity about the liturgy,” said the Rev. Will Wauters – assisting priest at Epiphany in 1980-82 and its vicar from 2002 to 2010 – whom Lopez invited to preach the homily at her memorial service. “This extended to the celebrations on the night of Epiphany when we would close the street in front of the church, and there would be dancing and music culminating in the Mariachi Mass. Lydia got it; she could see all the pieces coming together: the liturgy with social justice and the culture. It all had to fit together. You couldn’t have the one without the other.”

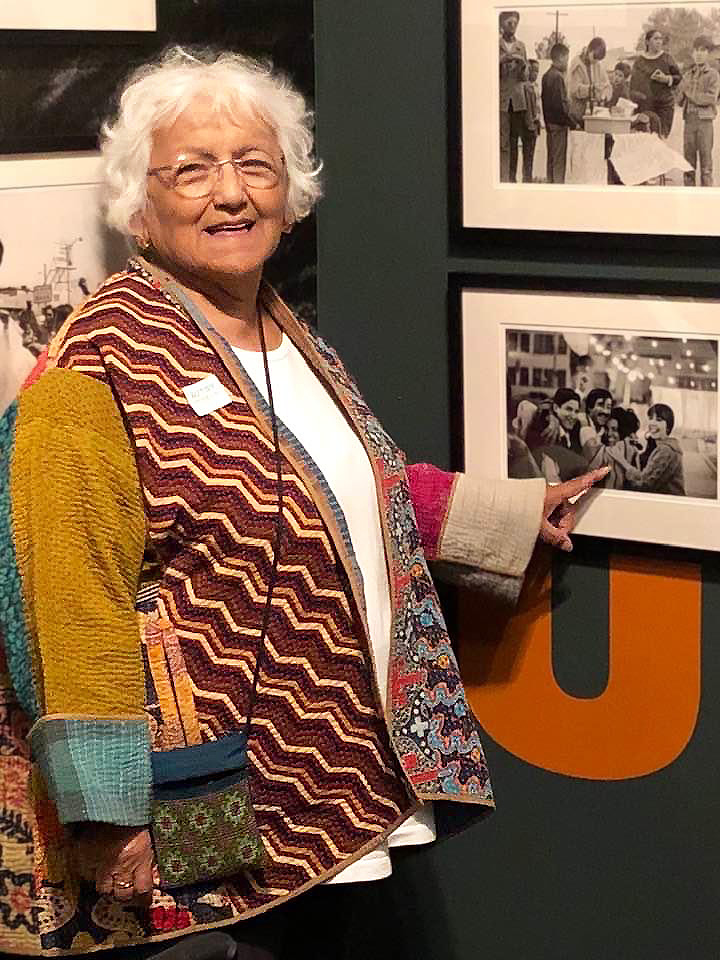

At the Autry Museum in Griffith Park, Canon Lydia Lopez points to a photo in which she is pictured as part of a 2017 exhibition documenting Chicano life in Los Angeles in the 1960s and ’70s. Photo: Mark Hallahan

The church was a hub of activity advocating for civil rights of Latinos including the United Farmworkers union, led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, who spoke regularly to gatherings on site. The Chicano movement’s newspaper, La Raza, was printed in the church basement. Lopez formed longstanding friendships and alliances with clergy, laity, and union leaders, most recently welcoming Huerta as keynote speaker to Diocesan Convention in 2019. Also friends with the Chavez family, Lopez attended Chavez’s funeral procession in 1993 in Delano, Calif.

“Church of the Epiphany became my school of theology,” Lopez recalled. “We were taught the theology of liberation. We began organizing and we went to work. We were taught about the need to work for justice and to care for the poor. And because of our work we were followed by the police and arrested, and some of our friends were killed.”

Aspects of these experiences are captured in photographs featured by the Autry Museum in a major 2017 exhibition documenting Chicano life in Los Angeles during the 1960s and ’70s. Photos of Lopez and her then husband, Fred, are included.

Lopez demonstrated her dedication to the parish’s legacy by helping to establish the Epiphany Conservation Trust in 2010, working with the Rev. Tom Carey, then vicar, to raise significant funds for historic preservation, teaming with local political leaders and architects, among others. At the request of Lopez’s family, memorial gifts may be made in her honor to the ministries of Epiphany via the church website, www.epiphanyla.net, or by mail to the church office at 2808 Altura St., Los Angeles, CA 90031.

Carey and Lopez were allied in strong collaboration and friendship. “In my life, I’ve had some important teachers,” Carey told The News. “Lydia Lopez was one of them. She saw the world clearly and was never shy about telling you what she saw. I love her bravery and her great heart. These are things that stay with you after death.”

During his 1981 visit to Los Angeles, Archbishop of Canterbury Robert Runcie (left) and Lydia Lopez (silhouetted at right) converse during Cinco de Mayo festivities at Church of the Epiphany, East Los Angeles. Episcopal News photo: Ralph Waycott

Earlier, in 1981, Lopez expressed her pride in Epiphany by helping to organize, at the invitation of then Bishop Robert Rusack, a visit to the parish by Archbishop of Canterbury Robert Runcie who on Cinco de Mayo celebrated a Mariachi Mass and preached. Ten bishops and 70 diocesan clergy were in procession. Lopez hosted Anglican envoy Terry Waite for an advance tour and arranged for L.A.’s then-Mayor Tom Bradley to join the festivities, also enlivened by folklorico dancing.

UNO, Sanctuary Movement

That year, Lopez was elected president of the United Neighborhoods Organization (UNO), founded as “a large-scale metropolitan, multi-issue citizens organization that is made up of parishes and congregations from East Los Angeles to deal with fundamental economic and social issues affecting the residents of that community.” To build its grassroots coalition, UNO applied the organizing principles of the late Saul Alinsky who in 1940 co-founded the national Industrial Areas Foundation in Chicago with then Bishop Bernard J. Sheil and businessman Marshall Field III. Employment opportunities, corporate reinvestment, and gang intervention were among objectives pursued by UNO under Lopez’s term of office.

One of Lopez’s close colleagues in that work was Father Richard Estrada, then a Roman Catholic priest in the Claretian order whom Bruno received as an Episcopal priest in 2014. “Lydia and I always said we’d known each other since childhood as we were both born in the spring of 1942 at L.A. County General Hospital,” Estrada told The News, also recalling their shared work in the sanctuary movement with the late Fr. Luis Olivares at La Placita Church where Estrada later became pastor. “Lydia will live on in us who really knew her, loved her, challenged her, and let her challenge us.”

Lopez often described her work with Olivares, serving as a key assistant and advisor to him, as one of the most personally meaningful chapters of her life and ministry. They also had been colleagues in the work of UNO before sharing in the ministry of providing safe “sanctuary” shelter, food and clothing to undocumented immigrant refugees at La Placita, the historic plaza Church of Our Lady, Queen of Angels, located in L.A.’s original Pueblo as the city’s oldest continuing house of worship.

Lopez said she was moved by the strength of the immigrants and their daily quest for finding work and better lives. “It was a very poignant moment to watch them leaving and watch them coming back,” she said in an interview with Mario T. Garcia, reported in his 2018 book Father Luis Olivares, a Biography: Faith Politics and the Origins of the Sanctuary Movement. “My heart would go out to them [as they slept on church pews at night]. How many churches do this? How many priests and ministers do this?”

Lopez poses with Dolores Huerta after the activist delivered the Margaret Parker lecture at the 2019 meeting of Diocesan Convention. Photo: Janet Kawamoto

Lopez remained in solidarity with Olivares through tensions with Archbishop Roger Mahony who held differing views of Olivares’ public declaration of sanctuary at La Placita. Lopez was also there to help support Olivares after he contracted the HIV/AIDS virus through a blood transfusion he received in El Salvador. The infection claimed his life in 1993. “I was always moved by the way she took care of Fr. Olivares,” Durazo, the state senator, said of Lopez.

Guadalupanas, interpreting the ‘needs of my people’

At the invitation of L.A.’s then Mayor Richard Riordan, Lopez served from 1994 to 1998 as president of the city’s newly formed El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument Authority Commission, providing added support for vendors and businesses along the city’s historic Olvera Street.

She also became both board chair and acting director of Plaza de la Raza in East Los Angeles, a Latino cultural and educational center then serving 800 youths weekly. Concurrently, she continued to advocate for construction of the Metro Gold Line, which in 2015 linked Pasadena and points east with Union Station downtown.

The significance of her history with the Pueblo deepened each year as she returned to La Placita for mananitas and the celebration of the Feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Each year, Lopez found ways of acquainting Protestant Christian friends with the traditions of the observance, inspiring them as fellow “Guadalupanas” inspired by the icon and related faith stories.

Exploring this intersection of traditions, the Wall Street Journal in 2002 interviewed Lopez, “the first Mexican-American to be named a canon in the Episcopal Church” in the Diocese of Los Angeles, who “has integrated Juan Diego’s visions into her religious life. ‘I’m a great fan of the Virgin of Guadalupe,’ she says. ‘She is a very important spiritual and cultural symbol who is not just for Catholics but for us all.’”

Lopez, center, works with other diocesan leaders at the Diocese of Los Angeles offices in this undated photo. Photo: Ruth Nicastro

When the churchwide Episcopal Communicators organization held its annual conference in Los Angeles in 2003, Lopez taught a workshop titled “Guadalupe 101” and led participants on a pilgrimage to the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, a walk that also showcased art by the Guadalupe project led by the Rev. Mary Moreno Richardson, a “comadre,” or close friend, of Lopez. “La Virgen crosses borders, is undocumented, and lives outdoors in solidarity with immigrants seeking a better life,” Lopez said at the time.

In a 2013 interview with a UCLA Library researcher, Lopez said she was “almost always having to interpret to my church the needs of my people and how to celebrate” cultural traditions.

Lopez did this work at denominational levels as a deputy to General Convention, as well as regionally in diocesan work, including her role as a founding leader of the diocesan Program Group on Latino/Hispanic Ministry, and as a liaison to companion-diocese relationships shared by Los Angeles with the Anglican Church of Mexico and the Episcopal Diocese of Jerusalem and the Middle East, respectively.

“Lydia and I first bonded over our mutual concern for justice in Israel and Palestine,” said Randy Heyn-Lamb, who with his wife, Doni, leads All Saints’ Middle East Ministries group and is active in diocesan global partnerships work. The Heyn-Lambs became devoted friends of Lopez. “Living nearby meant we were chauffeurs to local events,” he said, “and my nursing experience proved helpful to in later years.”

Another longtime friend, Grace Dyrness, met Lopez in the 1990s at an immigration protest for Salvadoreans. “Lydia and I had an instant soul connection because of our backgrounds: she Mexican, me Central American,” Dyrness said. “Our love of all things Mexican, indigenous, Central American, Latino, drew us together — to that we were completely in sync with a passion for justice, for the marginalized and oppressed, that soon drew us to the world.

“We could talk hours and hours about what was happening in the Middle East, in Africa, in South Asia,” added Dyrness, who will deliver one of the eulogies at Lopez’s memorial service. “War to both of us was an abomination, and the late George Regas (All Saints’ longtime rector) mentored us in how to use our faith to oppose war, especially through the work of Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace (ICUJP). But talking was not enough for us and together we joined many others in actions opposing our country’s policies.”

Upbringing in Whittier

Lopez was born April 20, 1942 in East Los Angeles to Mexican immigrant parents. Her father was a migrant worker who after her birth went to work at an area steel mill from which he retired, bringing Lopez an early introduction to labor unions. An expert seamstress, Lopez’s mother, whose brothers also were migrant workers, was renowned as well for her culinary skill. She prepared homemade tortillas and other traditional specialties with recipes then handed down to Lopez, also an excellent chef. Lopez said it was her mother’s gift for hospitality that inspired her own enjoyment of entertaining.

The family lived in Whittier – a Quaker colony named for the poet John Greenleaf Whittier – in a west-side barrio known as “Jimtown,” an unincorporated county area that was home to Mexican Americans living in houses built along its unpaved streets. In the mid-1950s, Jimtown was razed to make way for the 605 Freeway after property was acquired – at less than fair market value – through eminent domain.

The family attended Calvary Baptist Church in uptown Whittier, where Lopez and her brother, the late Ben Rodriguez Sr., were enrolled in Whittier Christian School, located adjacent to the church. They completed kindergarten through 8th grade there before advancing to Whittier High School.

Lopez said that having roots in evangelical Christianity helped her build understanding and identify common ground for conversations with others in mainline and other faith traditions, claiming the Episcopal Church’s historical role of bridge-building as the “via media” or middle way.

“To me, living one’s faith should open you to the world, not close you off from it,” Lopez said in her 2013 UCLA Library interview. “We’re supposed to love people, to listen to people, to try and do away with judgment.”

— Robert Williams, diocesan canon for common life, is Diocesan Convention’s appointed archivist-historiographer. He and Lopez were friends for more than 35 years.