In Jerusalem, a holy city to warring peoples, archaeology is power. Archaeology is also agony.

Riddle me this. Is the property at Jerusalem’s heart Har ha’Bavit, the Temple Mount, where Jewish temples once stood and our Lord Jesus Christ visited and taught, or al-Haram al-Sharif, the Noble Sanctuary, where two of Islam’s holiest buildings stand today?

One might say it can be both. Can’t everyone just get along? Maybe someday. But not yet. The wounds are too deep. So it is not for me to judge.

There would be no question in the minds of the men I saw midday Friday, making their way from East Jerusalem through the Old City to services at the Al-Aqsa mosque. Palestinian authorities have sometimes even claimed that the Jewish temples never existed. That isn’t all Palestinians. Just enough to stoke distrust and rage.

Whereas some Jewish sects say Islam’s shrines have no business there, though the oldest, the Dome of the Rock, was built in the seventh century. A millennium and a third is just a moment here. These sects want to destroy it all and replace it with a Third Temple, animal sacrifices and all. They’re already building the fixtures. You can donate to their non-profit. That isn’t all Israelis. Just enough to keep tensions high as extremists pick fights periodically with those going to say their prayers on sunny Fridays like today.

The ambiguity cuts deeper when you realize that our understanding about the layers of life in this ancient place comes at a horrible price.

For instance, I revisited the Jerusalem Archaeological Museum today. It forms an L embracing the southwest corner of the Temple-Sanctuary. The woman who sold me my ticket persuaded me to pay five shekels extra for access to an app that would play through my phone and hearing aids.

It wasn’t curators and academics, as I’d hoped. It was a drama with actors and music, taking the visitor back to Second Temple times. The narrator talked about the discoveries that had been made under the “dirt and trash” after Israel reclaimed Jerusalem in the 1967 war. What really happened is that Israel seized and destroyed Palestinians’ homes, a layer of life sacrificed to learn about those beneath. (For balanced insights about the politics of archaeology in Israel and Palestine, check out the work of עעמק שווה – Emek Shaveh, an Israeli NGO.)

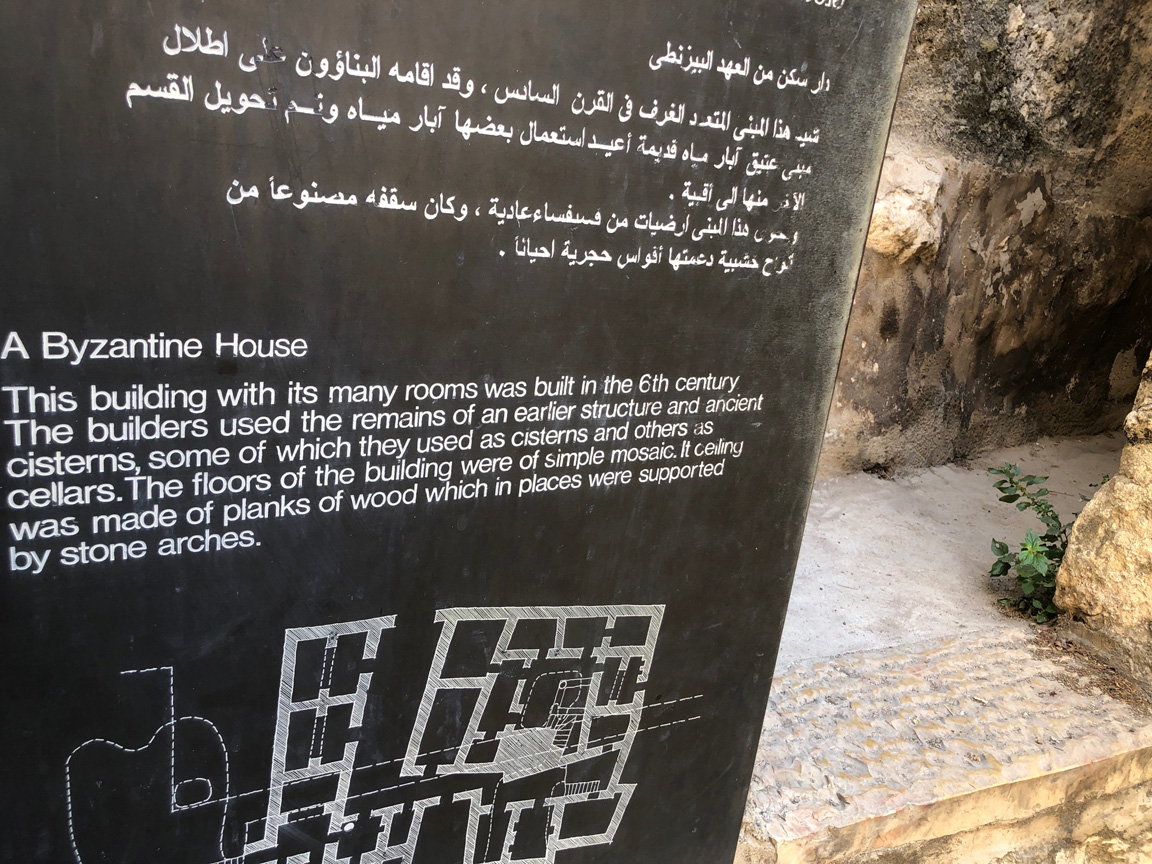

I turned the museum’s app off, but I stayed, climbing up and down catwalks through breathtaking ruins of Byzantine- and temple-era homes. I’m glad we know about them but repent of our means of knowing. In our time of deeper understanding about how we appropriate one another’s cultures, the decision to visit any museum can be an exercise in Christian ethics, but probably no more so than in Israel and Palestine.

I got a little payback along those lines. The Christian experience, as far as I could tell, is not part of the museum’s narrative. In fairness, the Davidson Center, the indoor display area, is closed. One of the most thrilling sites is Robinson’s Arch, actually a remnant of an arch that, experts surmise, supported a massive staircase connecting the lower market street to the temple. Christians are wont to say that the moneychangers Jesus confronted occupied stalls in the marketplace. You’ll hear it from pilgrim guides but not the Jerusalem Archaeological Museum, nor probably from the Birthright Israel tour leader who gathered his disciples today in a bit of shade thrown by the temple wall, by the Noble Sanctuary.

What can’t be overlooked — it’s actually why I go back to this museum — is a pile of stones which, it is said, Roman soldiers and pillagers threw down when they destroyed the temple in A.D. 70. The paving sags from the impact and weight. Seeing them is as vivid an historical experience as I’ve ever had. It was a sinning culture trying to destroy a layer of life of another’s. But they failed. Rome’s savagery inaugurated both the Jewish diaspora and Christianity’s global project. We are still living in a world constructed from those falling stones. Here, two millennia are just a moment.